Open science advocates Michael Bertram (Proceedings B Associate Editor), Thoré, Tomas Brodin (all from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) and Alfredo Sánchez-Tójar (Bielefeld University) share their thoughts on moving towards an open science community.

The theme for this year’s Open Access Week is ‘Community over Commercialisation', which aims to encourage conversations about which approaches to open scholarship prioritise the best interests of the public and the academic community. Open science advocates Michael Bertram (Proceedings B Associate Editor), Eli Thoré, Tomas Brodin (all from the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences) and Alfredo Sánchez-Tójar (Bielefeld University) share their thoughts on moving towards an open science community.

Science has been grappling with a replication crisis for almost two decades. A substantial body of evidence indicates that research spanning diverse fields is susceptible to findings that cannot be reliably replicated or reproduced. Prominent examples of this include a 2015 effort to replicate 100 psychology studies that failed to do so for more than half of them, a 2018 examination of social science experiments published in Nature and Science in which only around half of the 21 results were successfully replicated, and a 2021 investigation of 158 effects in 23 papers in preclinical cancer biology in which 92% of replication effect sizes were found to be smaller than the original. So, what is at the root of this lack of replication?

Numerous factors contribute to reduced replicability, such as inadequate methodological and/or statistical training, low statistical power (e.g. insufficient sample sizes), questionable research practices (e.g. p-hacking, selective reporting), financial or professional conflicts of interest, and deliberate fraud (e.g. data fabrication and falsification). These factors vary in terms of researchers' awareness and culpability, with much attention having recently been paid to several high-profile cases of scientific misconduct, including in the fields of behavioural ecology and ocean acidification. However, relatively more innocuous factors can also have major impacts on the consistency of research findings. This was underscored recently in ecology and evolutionary biology by a large-scale ‘many analysts’ project in which more than 200 researchers analysed the same sets of ecological data and generated widely divergent results due to their analytical decisions alone. In this regard,International Open Access Week represents an opportunity to reflect on one of the most significant and valuable approaches to addressing the replication crisis: open science.

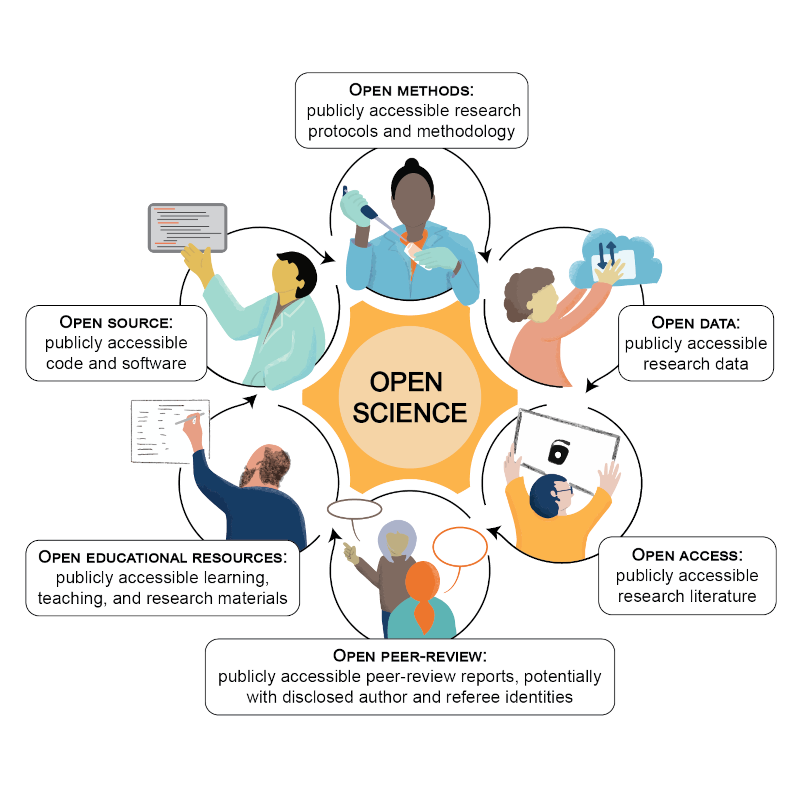

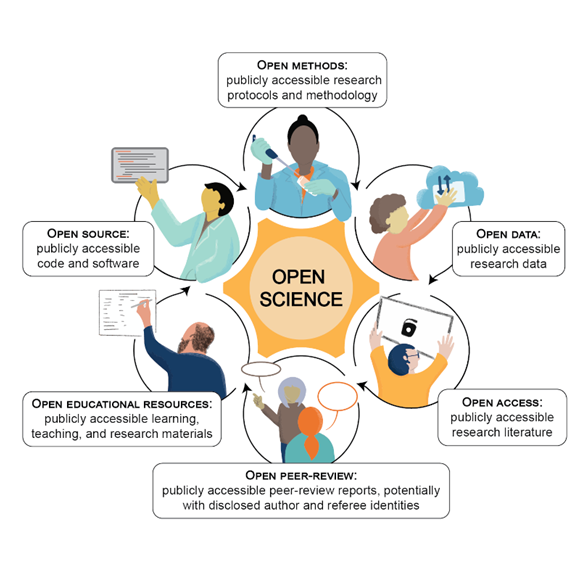

Open science encompasses a variety of approaches, instruments, platforms, and procedures with the goal of enhancing the accessibility, transparency, reproducibility, and reliability of scientific research. It involves actions such as sharing data, code, and materials, adopting innovative publication formats like registered reports and preprints, conducting replication studies and reanalyses, enhancing statistical methodologies for more robust evidence evaluation, and reassessing institutional incentive structures. Furthermore, open science aligns with the principles of fairness, diversity, and inclusivity. Its objective is to broaden access to the generation, appraisal, and dissemination of scientific knowledge, extending this access to scholars who have been historically marginalised, and to the members of society who are outside of the conventional scientific realm.

The core principles of open science. Open science embraces principles to make science accessible, transparent, and reliable, and thereby avoid common threats to reproducibility and replicability (e.g. questionable research practices, confirmation bias). (Figure 1, doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.036)

Although there is still a long road to making science more open and inclusive (e.g. the cost of publishing open access can be prohibitively expensive), it is important to acknowledge that substantial progress is being made in this space. Journals, funding organisations, and academic institutions have been revising their policies and incentives to support openness. For instance, in 2022, 61% of papers published in Royal Society journals were open access, an increase from 53% in 2021. In addition to top-down policies and incentives, the normalisation of open science relies heavily on the formation of grassroots communities of practice. These open science communities are often informal learning groups that facilitate interactions among researchers with varying levels of expertise, encouraging mutual support and knowledge sharing. Crucially, these communities play a significant role in establishing open science as a standard practice. They do so by actively contributing to the development of open science infrastructure, innovation, and policies. Furthermore, these communities increase the visibility of open science practices, a vital yet sometimes overlooked element in accelerating their adoption.

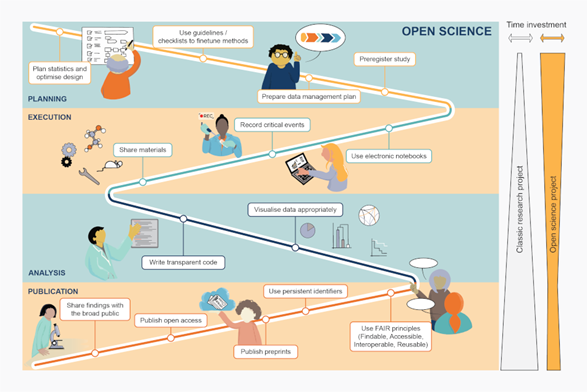

Examples of open science practices that can be implemented throughout the research lifecycle. Implementing open science practices at various stages of a project (planning, execution, analysis, and publication) helps to maximise the impact of science. The different practices within each stage are not necessarily in strict chronological order. Typically, engaging in open science practices requires a greater time investment in the early stages of a research project (front-loaded) compared to classic research projects, which are often rear-loaded. (Figure 2, doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2023.05.036)

Presently, there are over 200 grassroots open science networks worldwide. For instance, the Society for Open, Reliable, and Transparent Ecology and Evolutionary Biology (SORTEE), which brings together researchers that are seeking to improve reliability and transparency in ecology, evolutionary biology, and related fields. Further, the ReproducibiliTea Journal Club Series empowers researchers to establish local open science journal clubs, and it has already expanded to 100 institutions in 22 countries. These open science communities often originate from the initiatives of individual researchers, but an increasing number of institutions are lending their support. Institutions are embracing these initiatives, providing financial backing, appointing ambassadors to champion these efforts, and recognising the contributions made by these communities. Open science communities aim to be inclusive, but strategically targeting historically underrepresented groups and the ‘early majority’—individuals who are inquisitive about open science practices but have not yet adopted them—can be pivotal in fostering a paradigm shift. Importantly, these communities extend beyond researchers and encompass students, staff, educators, and other stakeholders, thereby promoting equity, diversity, and inclusion. Initiatives like the International Network of Open Science and Scholarship Communities (INOSC) offer resources to assist researchers in establishing and nurturing local open science communities at their institutions (www.startyourosc.com).

In summary, while open science practices have not yet become universally adopted, they are undeniably reshaping the landscape of scientific research. This transformation is not solely the result of top-down incentives and policies but is also driven by bottom-up efforts, such as those facilitated by grassroots open science communities. As such, it is vitally important for institutions to recognise and support the crucial role of these communities in driving positive change in science.

Find out more about the Royal Society open access policies on our website.