Eleanor Stephenson dissects the life of John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery, President of the Royal Society from 1686 to 1689 and a man described by his enemies as 'half way to hell’ and ‘as ugly in face as in fame’.

John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery (1639-1713), was governor of Jamaica from 1675 to 1678 and then President of the Royal Society from 1686 to 1689. His career, therefore, connects the histories of the early Royal Society (founded in 1660) and the early English Caribbean.

John Vaughan, by Peter Lely, c.1670, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

John Vaughan, by Peter Lely, c.1670, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

For my PhD research, I’ve been trying to piece together fragments of Lord Vaughan’s life in London and Jamaica, as he remains an elusive figure. I wanted to learn more about Vaughan – was he as terrible as his acquaintances described, and what did he do in Jamaica? I searched for his family archive and found that, although most had been destroyed in a fire in 1729, the Carmarthenshire Archives in south Wales held boxes of personal material. So, in late July, I hit the road to Carmarthen!

To learn more about Vaughan’s reputation, I began at the end of his life. Vaughan died in January 1713 at his residence in Tite Street, Chelsea, later called Gough House. Among his Chelsea neighbours was Sir Hans Sloane, another Royal Society Fellow (and later President) with links to Jamaica, whose Chelsea estate included the Chelsea Physic Garden from 1713.

Another neighbour, Ralph Palmer of Little Chelsea (now Fulham Road), summarised Vaughan’s life and death in a letter to his brother-in-law, John Verney, 1st Viscount Fermanagh. Palmer wrote that Vaughan ‘had been with his banker, and returning home sickened and died presently. He had redeemed his estate and amassed wealth by the government of Jamaica, where he carried many shauntelmen of Wales with him, and sold ‘em there for slaves, as he did his chaplain, to a blacksmith’.

Vaughan’s servant, according to Palmer, ‘believed [Vaughan] was by that time got half way to hell’. This accusation, as well as comments by Samuel Pepys and Edward Hyde, 1st Earl of Clarendon (who were both profiting from Atlantic slavery) that Vaughan was ‘one of the lewdest fellows of the age’ and ‘as ugly in face as in fame’, have dominated his legacy. So, who was Vaughan, and did his enemies have just reasons to defame him?

View of Golden Grove, c.1760, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

View of Golden Grove, c.1760, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

Vaughan was raised at his family seat in Carmarthenshire, Golden Grove. The Vaughan family descended (or so the family tree claims) from medieval royalty, including Hywel Dda, King of Wales, and William the Conqueror. In the mid-fifteenth century, they solidified their position at court through the marriage of Sir Griffith Vaughan and Katherine Tudor, King Henry VII’s great-aunt. The Vaughans continued to stay close to the royal family – after King Charles I’s execution, the royal chaplain, Dr Jeremy Taylor, fled to Golden Grove and tutored the young John Vaughan. These royal connections were central to Vaughan’s selection as governor of Jamaica and, later, as President of the Royal Society.

Detail of the Vaughan family tree, courtesy of Archifdy Sir Gâr / Carmarthenshire Archives

Detail of the Vaughan family tree, courtesy of Archifdy Sir Gâr / Carmarthenshire Archives

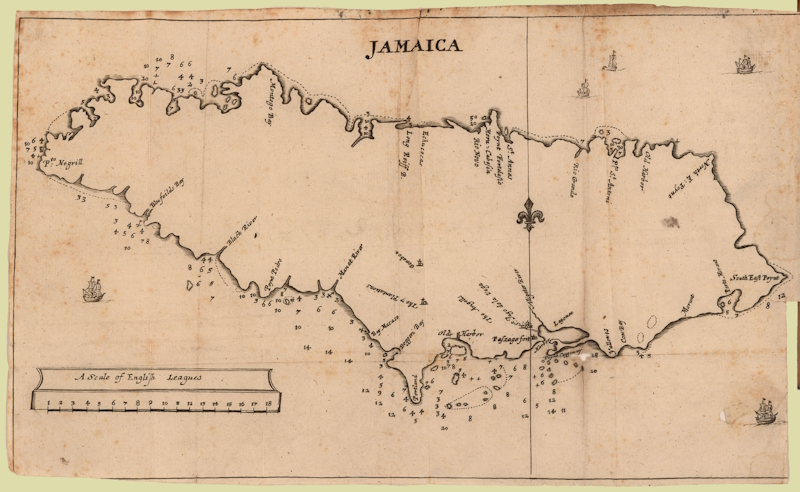

The island of Jamaica had been the consolation prize of Oliver Cromwell’s ‘Western Design’ in 1655, which the restored Stuart monarch, King Charles II, chose to retain. In 1660, the King’s Privy Council heard from people familiar with Jamaica, including Thomas Povey and Thomas Lynch, who recommended that ‘a person of Honour & Reputation be commissioned’ to govern Jamaica. The governor would represent the Crown on the island, and protect royal interests, for example, by encouraging the Royal African Company’s trade in enslaved African people.

Edmund Hickeringill, Jamaica viewed, 1661 (source: Brown University)

Edmund Hickeringill, Jamaica viewed, 1661 (source: Brown University)

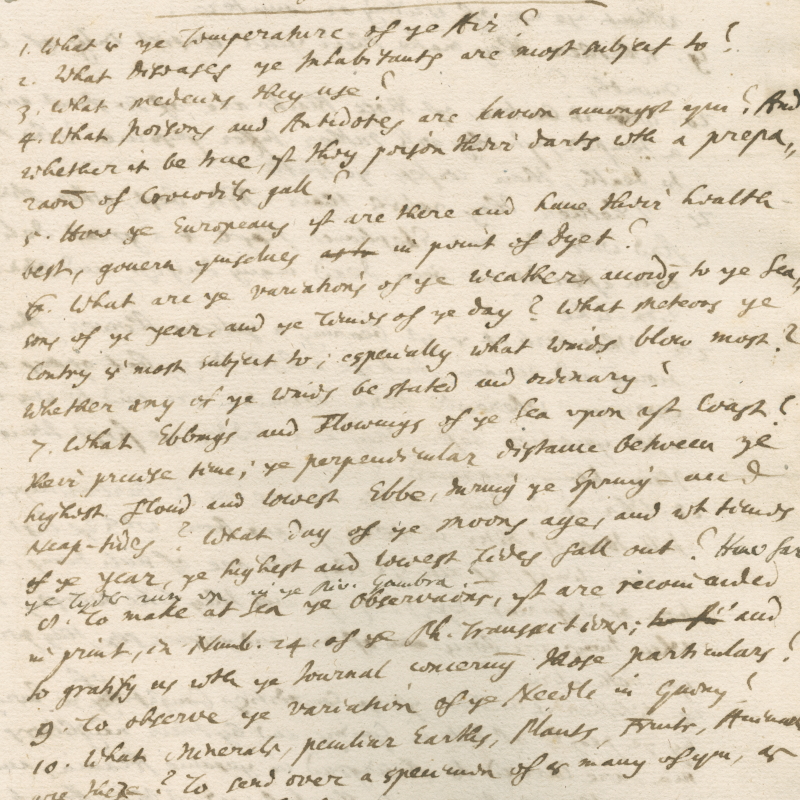

Lord John Vaughan was certainly a person, some might consider, ‘of Honour’ – he had been knighted in 1661 and sat as MP for Carmarthen from 1661 to 1679 – and he shared the King’s interests in science and commerce. Though his primary interests were mathematical, during his governorship of Jamaica Vaughan offered the Royal Society’s Secretary, Henry Oldenburg, ‘what assistance I can give’ in observing the natural history of Jamaica and even sent him ‘some samples of the productions of this Iland’.

Vaughan joined the pre-Charter Royal Society in 1661, though this only became ‘official’ when he was re-elected to the incorporated Society in 1685; a year later, he was chosen as President. Vaughan was also an early investor in the Royal African Company and, while in Jamaica, purchased enslaved African people from the Company, and encouraged the royal customs revenue by instructing ‘Naval Officers that ye Acts of Trade & Navigation will be punctually observed’. He thus supported the Crown’s interests in profiting from colonial expansion and the Atlantic slavery system.

Vaughan's family’s history of involvement in colonisation might have also contributed to his election as governor of Jamaica. Sir William Vaughan (c.1575-1641), John’s uncle, founded a colony in Cambriol (Little Wales) in Newfoundland in 1617, settled by Welsh indentured servants, but the settlement failed, and he transferred his interests to Virginia. Another uncle, Edward Vaughan (fl. 1639), established a successful plantation in Barbados. The database of indenture contracts shows that ‘John Vaughan’ – possibly Lord John Vaughan - acted as the agent for nine people who sold their labour for a tenure. These people left Bristol, the closest port city to Golden Grove, for the Americas, alongside hundreds more men and women from Wales.

Some of these people might have been tenants on Vaughan’s land, which spanned thousands of acres in South Wales. According to his banker, Mr Davies, Vaughan received £8,078 (almost £1.4 million today) from ‘Land Rent’ in Wales in the period from 1708 to 1712. Through the fee farm system, Vaughan rented land in Carmarthenshire owned by Edward Colston to farmers, further complicating colonial connections in the Welsh landscape. In a letter to Charles Howard, Earl of Carlisle, Vaughan’s successor as governor and another early Fellow, a Jamaica-based informant called Mr Nevil described Vaughan’s ‘mercenary tricks of selling his own servants and his own honour together’ while in Jamaica. Frustratingly, ‘all the writings … were also burnt’ during the 1729 fire at Golden Grove, which means we might never have direct evidence for Vaughan sending his Welsh ‘shauntelmen’ to the Americas, but it is clear that Vaughan was profiting from people and places in Wales and Jamaica.

During his short stay in Jamaica (1675-1678), Vaughan acquired lands totalling some 7,737 acres, with place names such as Golden Grove in the parish of St. Thomas and Llandilo in Clarendon harking back to his Welsh estates. There was also the Vaughan estate in the parish of St. Maries, which he appears to have named after his first wife, Mary Brown (d. 1674). According to his descendants' Jamaica-based solicitors, ‘Lord Vaughan’s Lands were well known through the Island’, and in the words of Mr Nevil, ‘his immoralities [were also] known and dreaded by the islanders’.

Vaughan purchased 43 enslaved African people from the Royal African Company, costing a total of £946 (equal to £183,494 today) – which included three girls and three boys. The Company’s records show that Vaughan was the first to purchase at every sale he attended in Port Royal – perhaps he was given priority as governor, or maybe he was desperate to start a slave plantation. It is not known what happened to these enslaved African men, women, and children, but given the acreage and number of people Vaughan bought, he might have planned to cultivate his land into plantations using enslaved labour.

According to his descendants’ solicitors, Vaughan continued to pay the bills for his land in Jamaica after he returned home and became the 3rd Earl of Carbery and President of the Royal Society. But by the early eighteenth century, if not before, ‘several [other] people have taken up the Lands and Settled them’, which suggests that Vaughan, if not his descendants, neglected the property and people he left behind in Jamaica.

Lady Anne Vaughan, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, c.1720, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

Lady Anne Vaughan, by Sir Godfrey Kneller, c.1720, courtesy of Carmarthenshire Museum

Vaughan’s daughter and only heir, Anne Vaughan, Duchess of Bolton (1689-1751), inherited the Jamaica estates, but as her marriage deteriorated, numerous bills, totalling thousands of pounds, were left unpaid. Therefore, the Crown confiscated the lands. It was not until 1753 that Anne’s second cousin, John Vaughan (1673-1765), tried to recover ‘3000 Acres of Lord Vaughan’s plantations’, but a bill for ‘The Jamaica Affair’ from 1764 suggests that the family ultimately failed to reclaim the land.

John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery, by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Oil on canvas, circa 1708. NPG 3196 (Creative Commons Licence)

John Vaughan, 3rd Earl of Carbery, by Sir Godfrey Kneller. Oil on canvas, circa 1708. NPG 3196 (Creative Commons Licence)

Lord Vaughan once wrote a poem which began, ‘There’s no such thing as good or evil, but that which does please or displease’. Vaughan’s moral indifference suited the Crown’s interests in profiting from colonialism and Atlantic slavery. But why did the Society elect him as President? Perhaps it was Vaughan’s royal and colonial connections, especially his role as governor of Jamaica, that attracted the Society’s Council. Vaughan had knowledge of the Americas – such as the flora and fauna of Jamaica – which suited the Society’s interests in learning about the world. Or maybe Vaughan’s election was a bid for the cash-strapped Society to secure royal funding.

But if the Council hoped to benefit socially and economically, they were mistaken. Vaughan never donated money to the Royal Society, nor is there any evidence of him fundraising, and his only identifiable contribution to Council Meetings was to transfer the East India Company shares that the Society had bought from John Evelyn to Sir John Lawrence. My research trip, therefore, revealed that Vaughan did fulfil some of his critics' claims, but also showed how royalist sentiment and imperial interests shaped his career and the history of the Royal Society.