Louisiane Ferlier reports on how researchers have been using the Royal Society's Science in the Making platform so far, and looks forward to future developments.

Eight months ago we relaunched Science in the Making, our online platform hosting over 30,000 items from the archives of the Royal Society. With 2024 around the corner, this seems the ideal time to look back at what we’ve achieved so far, and to analyse how researchers are using the site to access the collections.

First, let’s talk numbers. As of 1 December, over 12,400 search terms had been entered by over 14,000 visitors who viewed a whopping total of 92,500 pages. These amazing statistics are somewhat skewed by the extraordinary level of attention we received at launch thanks to the wonderful press coverage we received. This included articles in BBC News, the Times and the Financial Times, a full-length episode of BBC Radio 4 Inside Science, still available to download, and a colourful chat I had with Brady and James from the YouTube Objectivity channel, which has been viewed by over 25,000 people.

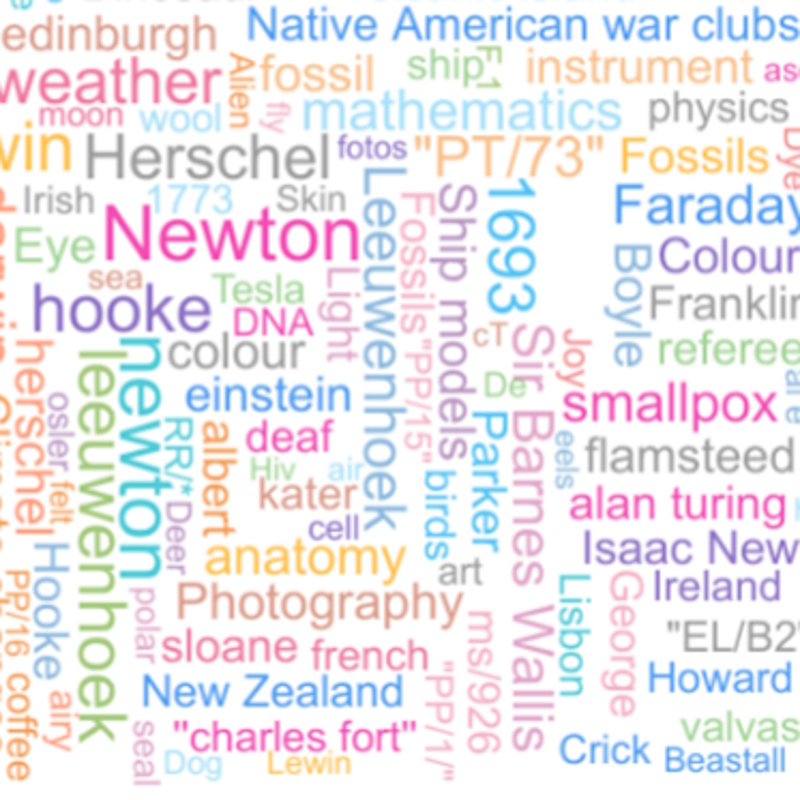

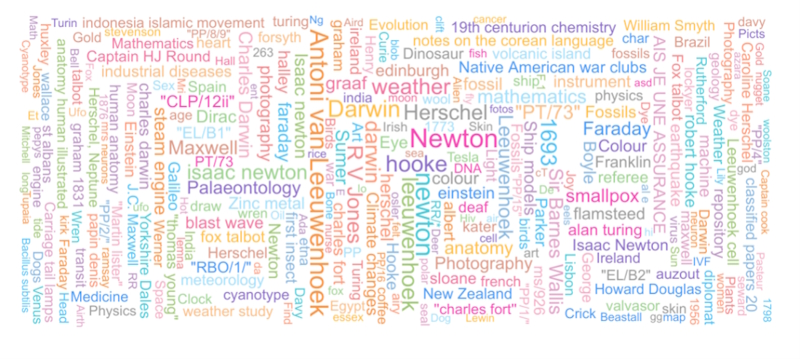

Since then we’ve been getting over 1,000 users every month, who – based on their searches and downloads – seem be conducting some fascinating research on a range of topics from cells to seals:

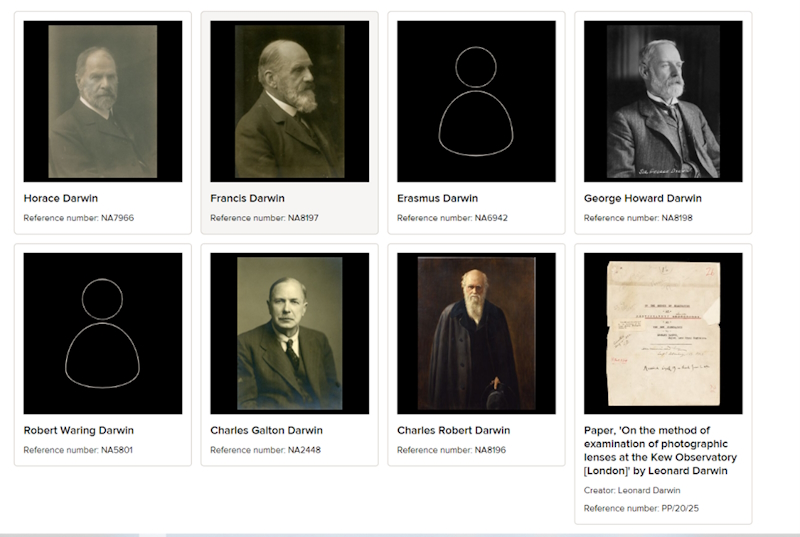

The most popular Fellows remain Sir Isaac Newton, Antoni van Leeuwenhoek and Charles Robert Darwin. In the last case, I’d strongly suggest that users search for his full name rather than just ‘Darwin’, as we also have material on the platform related to the following Darwins: Horace Darwin FRS, Francis Darwin FRS, Erasmus Darwin FRS, George Howard Darwin FRS, Robert Waring Darwin FRS, Charles Galton Darwin FRS and Leonard Darwin!

Our users also seem to have found our website via a variety of routes, including the Library of the National University of San Marcos in Lima, Peru; Explorersweb; and an article published in the Folha de S. Paulo. I’ve also received emails on an amazing variety of topics, from this paper on poisons used by the Manyika people to the chemical work of Smithson Tennant FRS.

Eight months on, I think Science in the Making is truly a success, reaching a wide cross-section of users conducting research across all fields of science. Rest assured though, this is just the beginning, as there is plenty to be done to improve the platform and its visibility and, of course, a lot more material to digitise in the collections.

To improve discoverability of our digitised manuscripts, a few months after the launch we added links from our online catalogue to items on Science in the Making. We’re now working with the Publishing team on ways of adding links from journal articles to their related archives on Science in the Making in 2024.

We also have a five-year plan to digitise new material to be added to the platform. However, I’d like to emphasise that we don’t take the decision to digitise lightly, for many reasons. Firstly, as custodians of the collection, our primary concern is for the physical material, so we always perform a thorough assessment before image capture – some items may be deemed too fragile for photography or require extensive and expensive conservation work before digitisation.

Secondly, digitising means creating digital surrogate files, which then have to be stored and cared for in perpetuity. This generates additional curatorial responsibility, and – very importantly – it has a tangible climate impact as servers are resource-intensive. In addition to the original cost of digitisation, which is not negligible, this commits the Society to ongoing maintenance and digital preservation.

Despite those challenges, I think it’s fair to say that Science in the Making is already key to delivering on our mission to open our collections and improve global access to key resources in the history of science and knowledge.

In closing, I’d love to hear more on how you’ve been using the platform, so drop us a line at makingscience@royalsociety.org – and stay tuned for our exciting plans for 2024!