Hirra Ateeq tells the story of Eleazar Albin, a naturalist and watercolour teacher whose popular books depicted birds, insects and spiders.

While preparing for our forthcoming exhibition on ornithology (watch this space!), I came across the intriguing figure of Eleazar Albin. I decided that he – and his beautiful illustrations of birds – were worthy of further investigation.

Albin – his exact life dates are unknown but he was active from the early years of the eighteenth century to c.1742 – was a naturalist and watercolour teacher who published works containing illustrations of birds, insects and spiders. His origins are equally obscure, though it is thought he was born in Germany to a family named Weiss and spent some time in Jamaica in 1701. By 1708 he had changed his name to Albin and was living in England, married with children. It was around this time he met naturalist and silk weaver Joseph Dandridge, who provided Albin with an introduction to natural history and had a lasting influence on his career.

The long-tailed titmouse in Albin’s Natural history of birds

The long-tailed titmouse in Albin’s Natural history of birds

In A natural history of English insects (1720), Albin relates how he was employed by Dandridge, ‘a very ingenious man’, to draw caterpillars. Dandridge then recommended him to Mrs Howe, the widow of physician George Howe, to paint caterpillars and flies. However, it was Albin’s introduction to Mary, Dowager Duchess of Beaufort, which led to the eventual publication of this volume. She encouraged him and provided financial support by securing subscriptions from notable individuals.

Privet hawk moths and Callajoppa exaltatoria by Eleazar Albin, 1720 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Privet hawk moths and Callajoppa exaltatoria by Eleazar Albin, 1720 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

After publishing his book on insects, Albin turned his attention to birds. Using his connections with naturalists to access large collections of exotic specimens, he published A natural history of birds (1731-1738) consisting of three volumes, under the patronage of Sir Robert Adby of Albyns, Essex and Richard Mead FRS, physician to King George II.

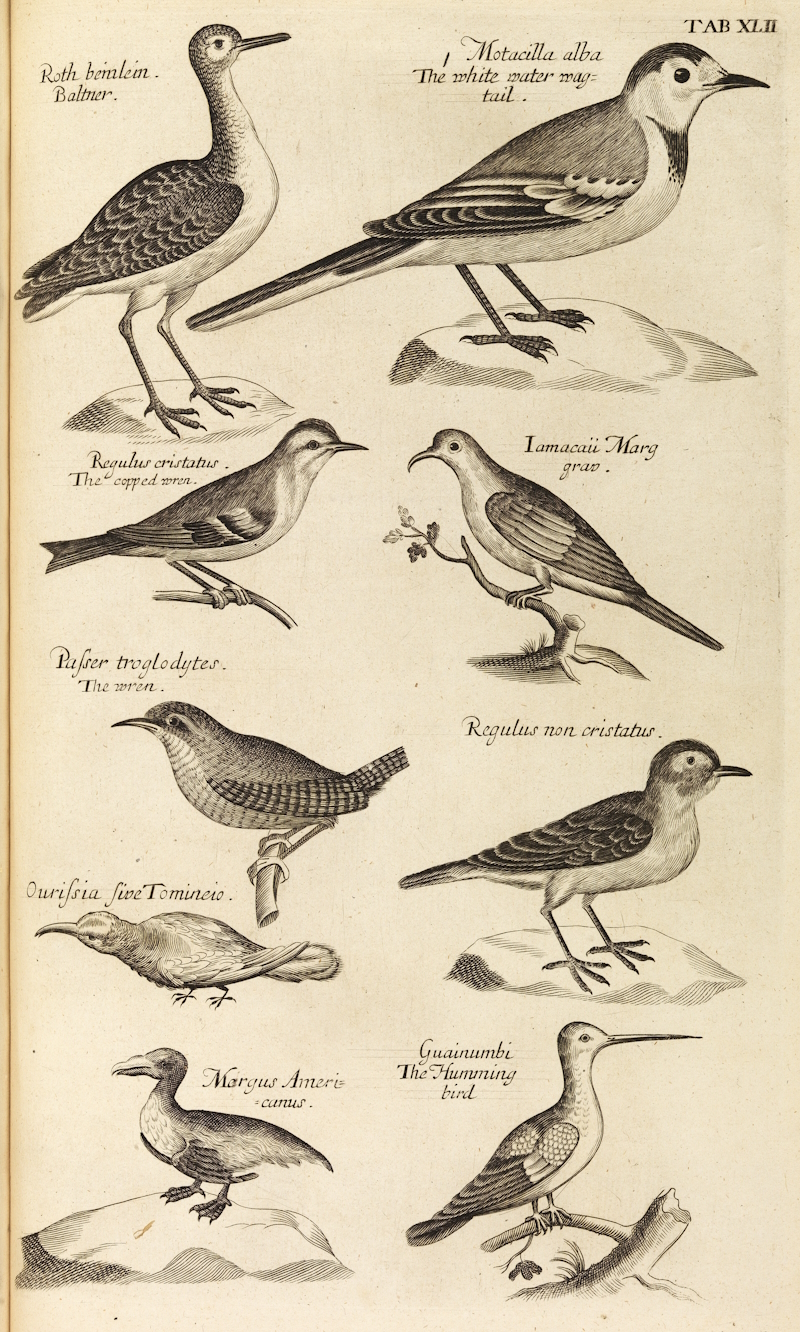

Illustration from Francis Willughby and John Ray’s Ornithology

Illustration from Francis Willughby and John Ray’s Ornithology

The influence of Fellows of the Royal Society in Albin’s work is apparent in the preface to the first volume of A natural history of birds, where he credited the Ornithology of Francis Willughby and John Ray as a source for his descriptions, while clarifying that he had also made observations of ‘the very Birds themselves’. Albin took particular care to describe their characteristics and specific differences, as well as noting their English and Latin names. He appealed to readers for specimens to complete the next volume: ‘I shall be very thankful to any Gentleman that will be pleased to send any curious Birds (which shall be drawn and graved for the second Volume, and their Names shall be mentioned as Encouragers of the Work) to Eleazar Albin near the Dog and Duck in Tottenham-Court Road.’ An amusingly ornithological location!

Chaffinch in Albin’s Natural history of birds

Chaffinch in Albin’s Natural history of birds

The painstaking work of Albin, and his illustrator daughter Elizabeth, is evident in the 306 beautiful plates. Several are unsigned, making it difficult to discern who exactly they were drawn by; the acknowledgment of Elizabeth’s contribution is a welcome departure, at least, in an era when natural history was dominated by men. This was the first large English ornithology folio to be illustrated exclusively with hand-coloured plates. It was showy, and successful as a natural history compilation aimed at a non-specialist audience.

‘Bengal sparrows’ in Albin’s Natural history of birds

‘Bengal sparrows’ in Albin’s Natural history of birds

Albin did have his critics, at least in terms of how widely he spread his collecting net: according to W S Bristowe in More about Joseph Dandridge and his friends James Petiver and Eleazar Albin, English naturalist and ornithologist George Edwards wrote somewhat sniffily that ‘what new birds he [Albin] has worthy of any notice are from Mr Dandridge’s collection’. Nonetheless the popularity of his book can be seen by the list of subscribers at the beginning of the volumes.

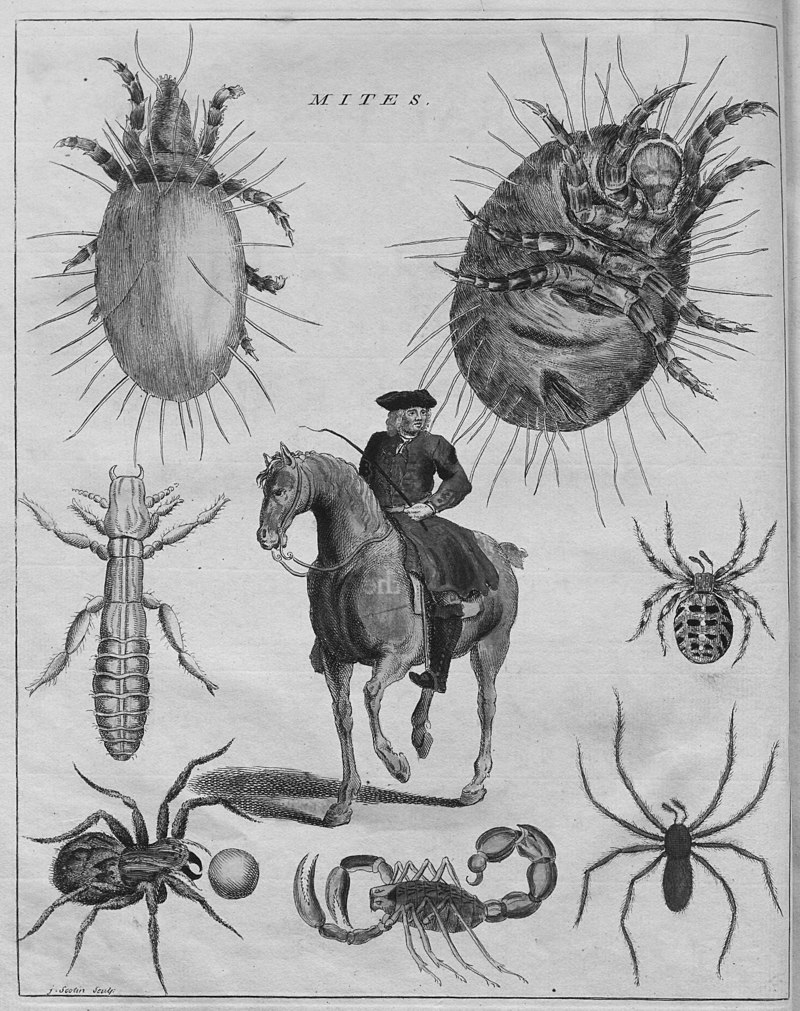

Frontispiece from A natural history of spiders, and other curious insects (1736) by Eleazar Albin

Frontispiece from A natural history of spiders, and other curious insects (1736) by Eleazar Albin

In 1736, part way through the publication of the three bird volumes, Albin produced the charming A natural history of spiders, and other curious insects. This included 53 copperplate engravings, each depicting multiple arachnids, hand-coloured by the author himself in some copies. The frontispiece features the only known likeness of Albin, depicted on a horse with several spiders and insects framing the page. However, as revealed in research by Bristowe on a collection of 119 drawings by Dandridge, along with descriptions and field notes (now in the Sloane Collection of the British Museum as Sloane MS 3999), Dandridge’s earlier work was used by Albin as the foundation of his book on spiders and insects, without any sort of acknowledgment. Tut tut, Eleazar!

Notwithstanding this rather unscrupulous example of lifting another’s research, from unknown beginnings Eleazar Albin became one of the major ornithological and entomological book illustrators of the eighteenth century. As one of the first artists to bring natural history to the non-specialist reader, he deserves a wider audience – something we’re hoping to remedy when our next exhibition goes live!