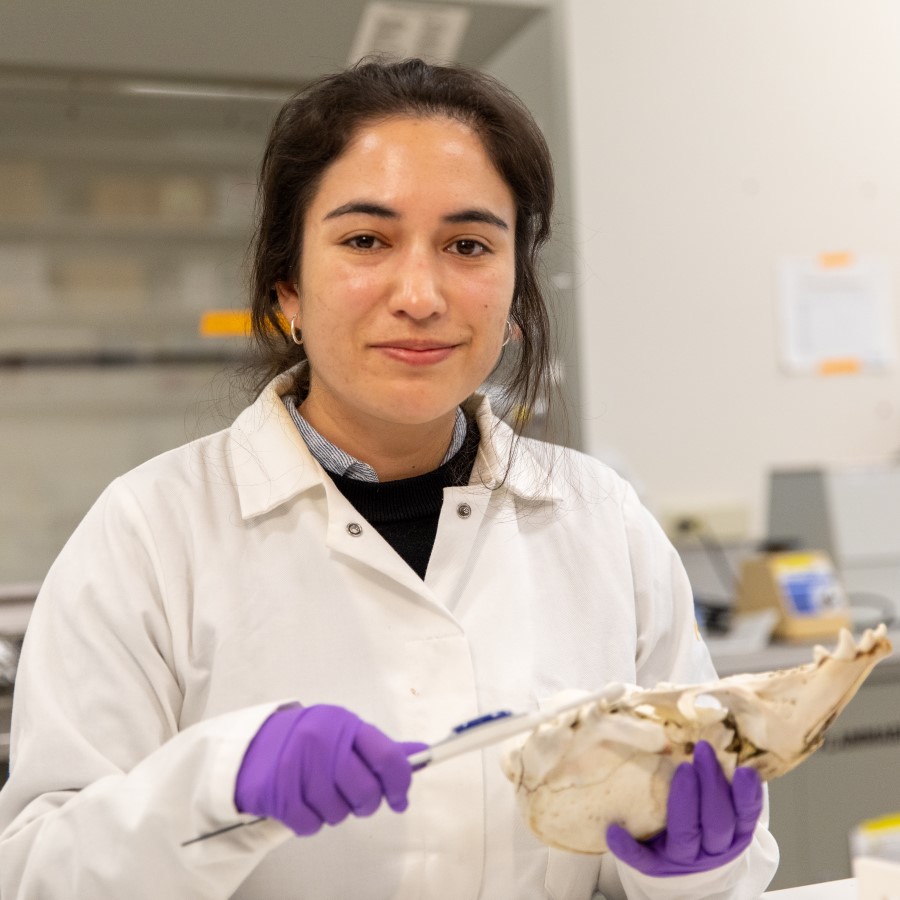

We hear from finalist, Ana Valenzuela Toro, about her research.

Biology Letters has been a home for quality research since 2005. In that time, we have cultivated great relationships with scientists from across the world and at different stages in their career. This is especially true for early career researchers (ECRs) who may be starting to submit their studies for publication the first time. With this in mind, we recently launched the Biology Letters Best Paper Prize for 2024 to highlight the best research articles published by ECRs. Entrants have until 30th April to submit their work, but in the meantime, we speak to last year’s finalists about their research and the prize.

In the first of three posts, we hear from Ana Valenzuela Toro about her paper on 'Feeding morphology and body size shape resource partitioning in an eared seal community'.

Tell us about yourself and your research article

I am a Chilean paleobiologist, and my research is devoted to studying marine mammals' evolutionary history and understanding the ecological, morphological, and physiological adaptations associated with their aquatic lifestyle and their evolution from terrestrial ancestors. Mainly, I seek to understand how pinnipeds have evolved and maintained a semi-aquatic lifestyle - breeding on land but foraging in the water over the past ~30 million years.

My paper in Biology Letters addresses a long-standing question in ecology, which is how do species coexist? Using a novel museum specimen-based dataset, my coauthors and I revealed that differences in body size and skull morphology contribute to resource partitioning among co-occurring eared seals from the northeastern Pacific Ocean. Our work shows that eared seals with larger body sizes and stronger bite forces consume larger prey, favoring resource partitioning with smaller individuals. Moreover, equivalent body size and morphological differences exist in other living and extinct marine mammal assemblages, indicating that similar strategies favoring co-existence have repeatedly evolved over geologic time.

Did you expect to be a finalist in our inaugural competition? And do you recommend that other early career researchers enter this year’s competition?

No, I didn’t expect it. I am passionate about my research, and I find it important as it addresses critical (yet unknown) aspects of how marine mammals organize their communities over ecological and evolutionary time, providing clues for predicting the effect of the environmental crisis. However, I recognize that some research can attract more attention than those involving “old and traditional” data sources like museum specimens, like mine. I am happy that my research was valued and made more visible, so more researchers will recognize the power of archival specimens for advancing pressing questions in ecology. I don’t conceive of research or science as a competition; however, it is fantastic to receive recognition from peers. I encourage all early career researchers publishing in Biology Letters to enter this competition.

What’s next for you and your work?

After finishing my Ph.D. in the US, I returned to my home country, Chile. Since then, I have been working as a scientist in a recently founded research center – CIAHN Atacama – in the Atacama Desert. This position has a special meaning for me because this region was where I started my research career years ago while an undergraduate student.

I am currently working on several projects focusing on unraveling how the marine mammal fauna (and the marine ecosystem) from the Pacific Ocean has transformed over the last 10 million years for which I am using different information sources, from beach bones to fossils, to population databases.

And finally, do you have any advice for upcoming generations of scientists in your field?

Although I am constantly discovering and (re)learning how to navigate academia myself, I would say that listening to diverse voices is crucial to pursuing a sustainable and successful scientific career. We all have different backgrounds and experiences shaping the way we think, the research questions we make, and even how we interpret the data. Discussing our ideas with others, especially those directly or indirectly affected by it, can be hard (criticism is hard!). However, it likely will result in new and creative ways to think about our research, expanding its quality and, from there, its impact. Still, we have to be conscious that some voices are louder than others; therefore, we have to make intentional efforts to ensure that we are listening to a broad range of people, not only those who follow the traditional expectations of how a scientist should look or come from. Likewise, regardless of where we are in the academic or research path, use your platforms to amplify the voices of those historically left behind. We must remember that not all scientists start their careers from the same point, and some experience several visible and invisible barriers that impede their career progress and their expertise from being recognized.

Check back here soon for the second of our finalists posts. All the successful entrants from 2023 can also be found on our special collection page. Please do enter our competition in the meantime or contact the editorial office for more information.

-------------------------------------------------------------------

Image credits:

Ana Valenzuela Toro profile picture, kindly sent by Ana.