To mark International Women’s Day, we tell the story of the first woman to pay a visit to the Royal Society.

Happy International Women’s Day! Last year, we marked the occasion in our Library blog with a piece on the earliest women scientists elected to the Fellowship of the Royal Society, from 1945 onwards. But who was the very first woman to pay a visit to the Society? To answer that question, we must go all the way back to May 1667.

As the minutes of the Council meeting on 23 May record, ‘It was resolved, that the Duchess of Newcastle, having intimated her desire to be present at one of the meetings of the society, be entertained with some experiments at the next meeting’. One week later, the Journal Book of ‘ordinary’ Society meetings relates the goings-on at Arundel House, the temporary home of the Fellows in the aftermath of the Great Fire of London:

‘The Duchess of Newcastle coming in, the experiments appointed for her entertainment were made:

First, that of weighing the air, which was done with a glass receiver of the capacity of nine gallons and three pints […] Next were made several experiments of mixing colours. Then two cold liquors by mixture made hot. Then the experiment of making water bubble up in the rarefying engine, by drawing out the air…’

Margaret Cavendish by Peter Lely, 1665 (detail). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

Margaret Cavendish by Peter Lely, 1665 (detail). Public domain via Wikimedia Commons

The ‘Duchess of Newcastle’ who witnessed this display of experimental natural philosophy was Margaret Cavendish (1623-1673), née Lucas, the second wife of the courtier and Royalist soldier William Cavendish, 1st Duke of Newcastle upon Tyne. By 1667 Margaret was already a renowned author, issuing books under her own name – highly unusual for a woman of the time. Her first work, the Poems and Fancies of 1653, included her thoughts on matter and atomism, topics that would have featured in the discussions of the ‘Newcastle Circle’ of exiled Royalists which surrounded Margaret, William and his brother Charles in Paris, and included Thomas Hobbes and future Royal Society Fellow Kenelm Digby.

In 1666 she published two significant works: the proto-science fiction of The Blazing World, and her Observations upon Experimental Philosophy. This latter book is partly a response to Robert Hooke’s Micrographia, published the previous year under the imprimatur of the Royal Society and setting out Hooke’s arguments that instruments such as the microscope were necessary to enable observers to understand the complexity of the natural world. Margaret Cavendish disagreed with this purely experimental approach, arguing that microscopes were unreliable and inaccurate devices, and that no experimenter could possibly judge ‘which is the truest light, position, or medium, that doth present the object naturally as it is’.

While this viewpoint led to some mockery, the real picture of Cavendish’s attitude to the ‘new’ experimental science is far more nuanced, as this excellent article from our Notes and Records journal explains. Rather than being against empiricism, she thought that it should be part of a broader picture encompassing speculative thought: ‘the best study is Rational Contemplation joyned with the observations of regular sense’. She was also firmly in agreement with the Society’s Baconian principles of using scientific investigation ‘for the Profitable Increase for Men’ – the improvement of agriculture and animal husbandry, for example – and with the desire of Fellows such as Robert Boyle and William Petty to disseminate new ideas in plain, straightforward language.

Nonetheless, in the wake of her criticisms in Observations upon Experimental Philosophy there must have been a certain frisson surrounding the Duchess of Newcastle’s visit to Arundel House on 30 May 1667. I’ve been dipping into a new biography of Margaret Cavendish, and was very taken with author Francesca Peacock’s assertion that, ‘To Cavendish, the esteemed savants of the Royal Society were little more than naughty boys who needed telling off.’

While our Journal Book description of the visit confines itself to the list of experiments shown to the Duchess (no microscopes, unsurprisingly), we do have an eyewitness account from a Fellow: Samuel Pepys, who wrote in his diary that he waited at Arundel House

‘in expectation of the Duchesse of Newcastle, who had desired to be invited to the Society; and was, after much debate, pro and con., it seems many being against it; and we do believe the town will be full of ballads of it […] The Duchesse hath been a good, comely woman; but her dress so antick, and her deportment so ordinary, that I do not like her at all, nor did I hear her say any thing that was worth hearing, but that she was full of admiration, all admiration.’

Charming. Of course, Pepys is hardly a champion of women’s rights even by Restoration standards, let alone twenty-first century ones, and the reputation of Margaret Cavendish has certainly seen a major rehabilitation in more recent times. Her rediscovery from a feminist perspective in the 1980s, focusing on her radical ideas on marriage and a woman’s role in the world beyond the narrow confines of childbirth and domesticity, was followed by the establishment of an International Margaret Cavendish Society in 1997. The Royal Society Library has a growing collection of books relating to Cavendish, including Francesca Peacock’s new biography and a 2016 novel in our Fellows in Fiction collection, Danielle Dutton’s Margaret the First.

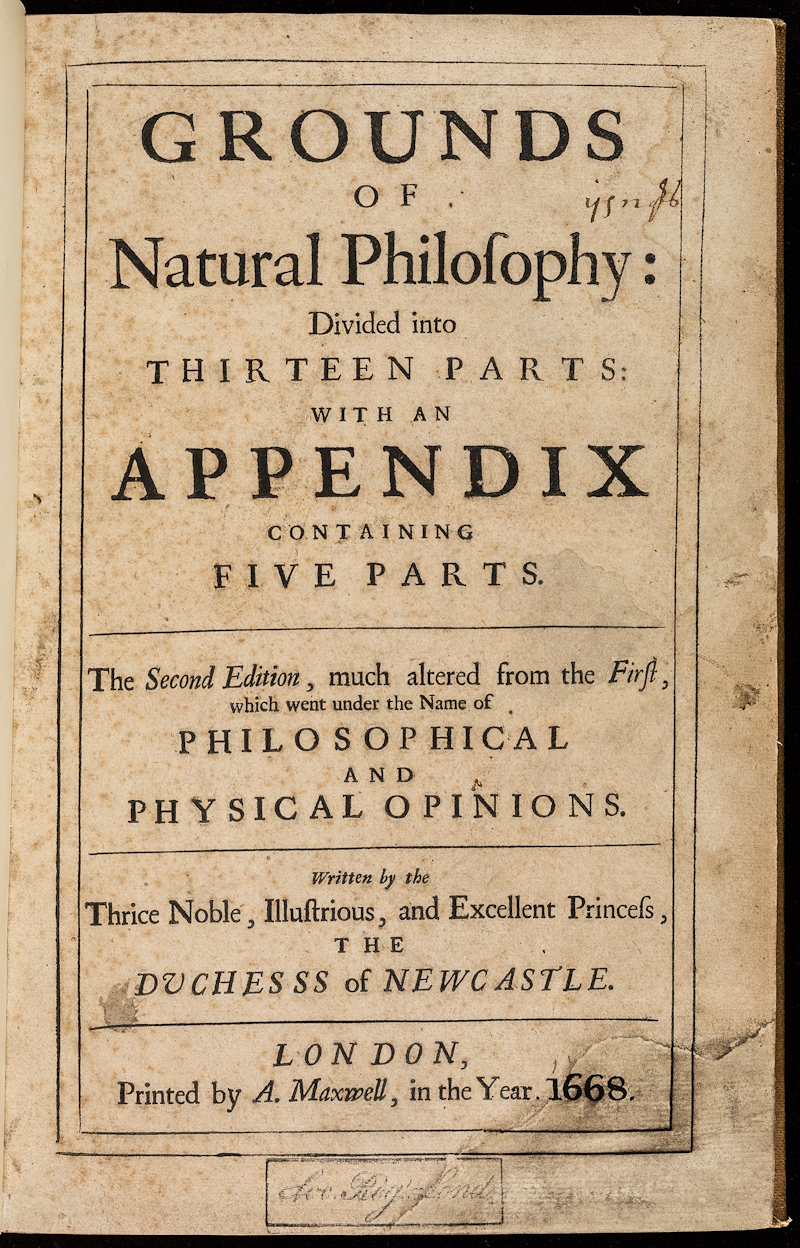

We also host regular Library visits for groups of seventeenth-century literature students, who always request to see the one contemporary Margaret Cavendish book in our collections, Grounds of Natural Philosophy (1668), itself an update to her earlier Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655). Placed alongside Micrographia, it has led to many stimulating discussions on the subsequent lengthy gap before other women were welcomed to the Royal Society, and on the debates raging at the time between early experimental science and Cavendish’s championing of ‘pure Wit, and the Effects of meer Contemplation’.