Bladder and kidney stones, and their causes and cure, were subjects of great interest to early Royal Society Fellows, as Lisa Jardine Grant Scheme recipient Caroline Curtis explains.

On 5 February 1662 fifty copies of a slim bound volume analysing the London bills of mortality were distributed among attendees at the Royal Society. By picking over the weekly burial bulletins, the haberdasher John Graunt hoped that his Natural and Political Observations Made Upon the Bills of Mortality would prove a useful and Baconian tabular evaluation of the consistency and regularity of plagues, births, murders, and other medical and social phenomena affecting the population of London.

Graunt also aimed to assuage the fears of those who supposed themselves to be constantly under threat of death: of the 229,250 deaths recorded in London in the past twenty years, comparatively few were recorded as having succumbed to ‘some of the more formidable and notorious Diseases’ including ‘Falling Sickness (74)’, ‘Jaundice (998)’, and ‘Dead in the Streets (243)’. A total of 863 deaths were attributed to ‘Stone and Stranguary’, while a further 38 succumbed to the effects of surgical lithotomy which attempted to remove these stones.

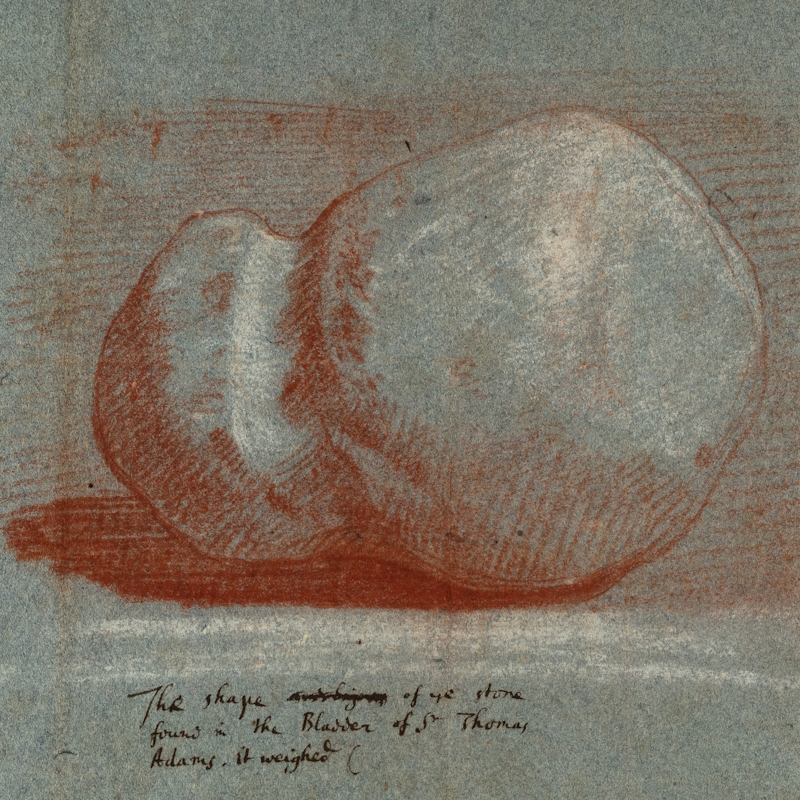

Drawing of a bladder stone by Robert Hooke, 1668 (CLP/14i/22)

Drawing of a bladder stone by Robert Hooke, 1668 (CLP/14i/22)

The identification and treatment of bladder and kidney stones (the concretion of minerals into solid crystals within these internal organs) is as old as the history of medicine. Various factors contributed to increased prevalence of stone disease in early modern Europe, chief among them an increase in protein consumption and limited water intake. Most stones range from 4 to 20mm in diameter; those measuring around 6mm or less are usually able to be passed through urination. The largest ever recorded, removed from a Sri Lankan patient in the summer of 2023, was 13.37cm in length. In the absence of spontaneous expulsion or dangerous surgical intervention a firm diagnosis of urolithiasis in the seventeenth century was usually postmortem.

Staghorn or stelliform, jagged rosette or amber gravel, the stone is one of those ‘diseases which most men know that feel them’ no matter which mineral forms the basis of the crystal, that ‘peculiar commodity’ of which Michel de Montaigne wrote that ‘we have but little to divine … Our senses tell us where it is and what it is’. Graunt’s assurance of diminishing frequency would bring small comfort to a reader seen ‘to brook convulsions, to trill down brackish and great tears, to make thick, muddy, black, bloody, and fearful urine, or to have it stopped by some sharp or rugged stone, which pricketh and cruelly wringeth’.

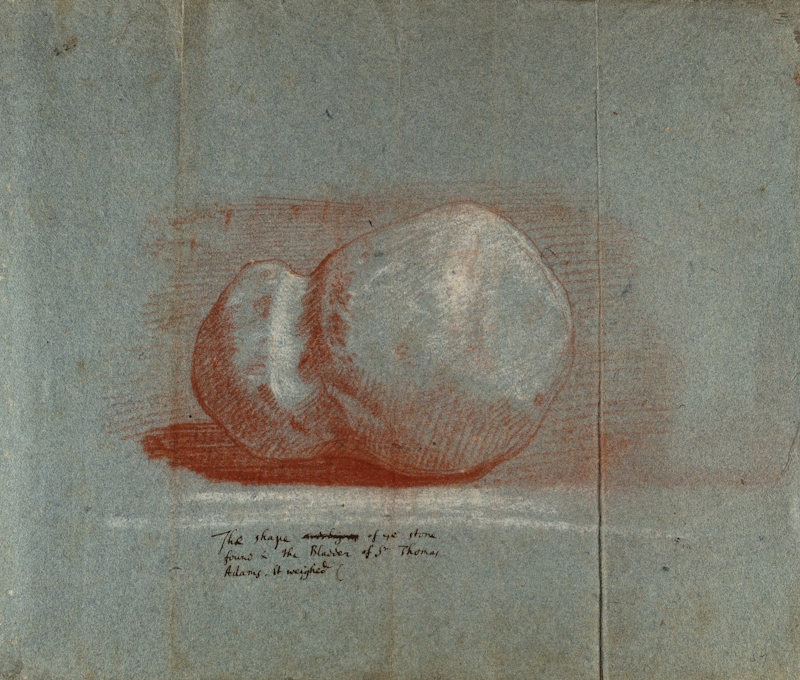

Curiosities in the Philosophical Transactions 1685: A bladder stone, a clay urn, and shells found in the kidney of a woman (RS.18748)

Curiosities in the Philosophical Transactions 1685: A bladder stone, a clay urn, and shells found in the kidney of a woman (RS.18748)

The causes and cure of bouts of the stone were evergreen subjects of interest. In 1658 at the age of 25 Samuel Pepys underwent open cystolithotomy to remove an agonising calculus from his bladder, resolving to keep the date of the surgery ‘a festival’ for the rest of his life; he also kept the stone itself and sought to have a case made to display it. In his Essays Francis Bacon had recommended bowling to ease the pain; Sir Isaac Newton’s final years were marked by recurrent bouts of the stone before dying in a bed which ‘shook with his agonys, to the wonder of those present’.

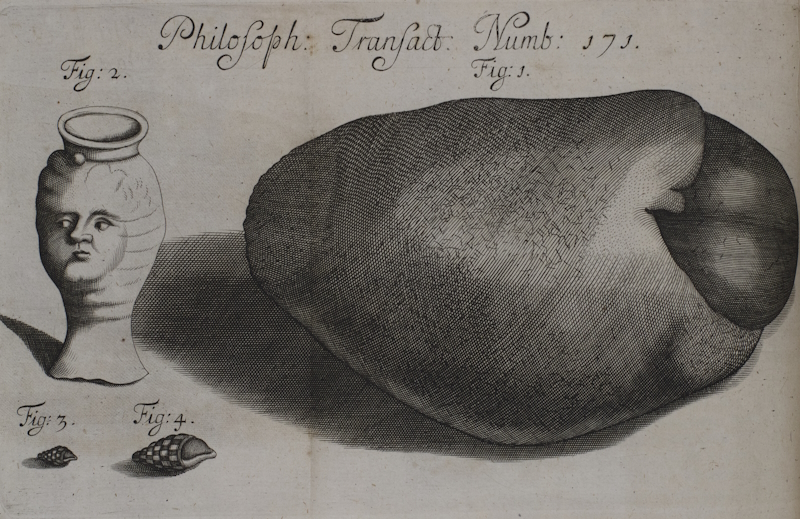

Robert Hooke’s observation of ‘Gravel in Urine’ (likely his own), Micrographia (1665) p.81, Sche.VII

Robert Hooke’s observation of ‘Gravel in Urine’ (likely his own), Micrographia (1665) p.81, Sche.VII

Complaints about the stone bookend Robert Boyle’s published life: his first publication in 1655 was a recipe for relieving the pain of the stone which he had written for the intelligencer Samuel Hartlib’s wife, while Boyle would complain of his own ‘stone’ among many other ailments in the introduction to his posthumously published Medicinal Experiments (1692). The collection of medical recipes for ailments such as fevers and kidney stones form the first series of his work diaries which record his development into a laboratorial investigator. They show him wrestling with the application of one universal recipe to the individual experience of disease and pain: in work diary 36 a stone taken from the kidney of a cow in Jamaica was brought by Sir Charles Lyttelton to be weighed and compared with an ‘Oriental Bezoar’ already in Boyle’s possession.

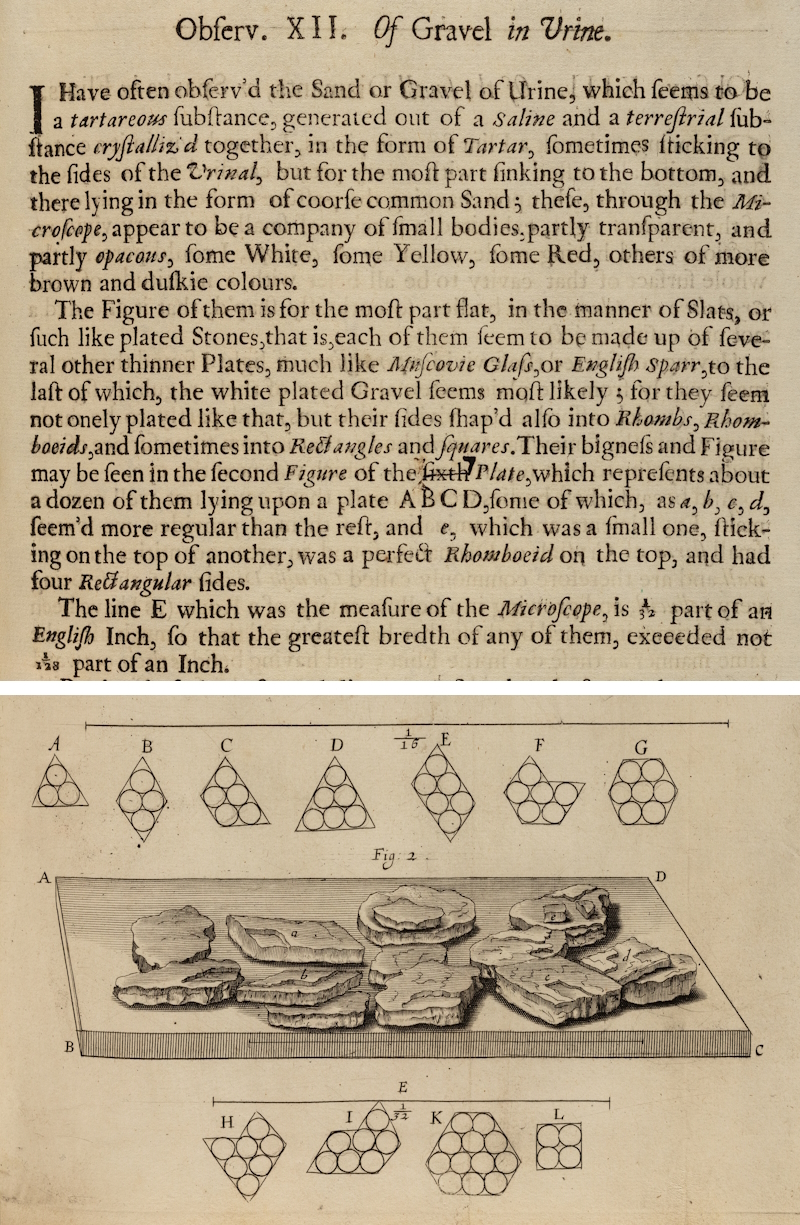

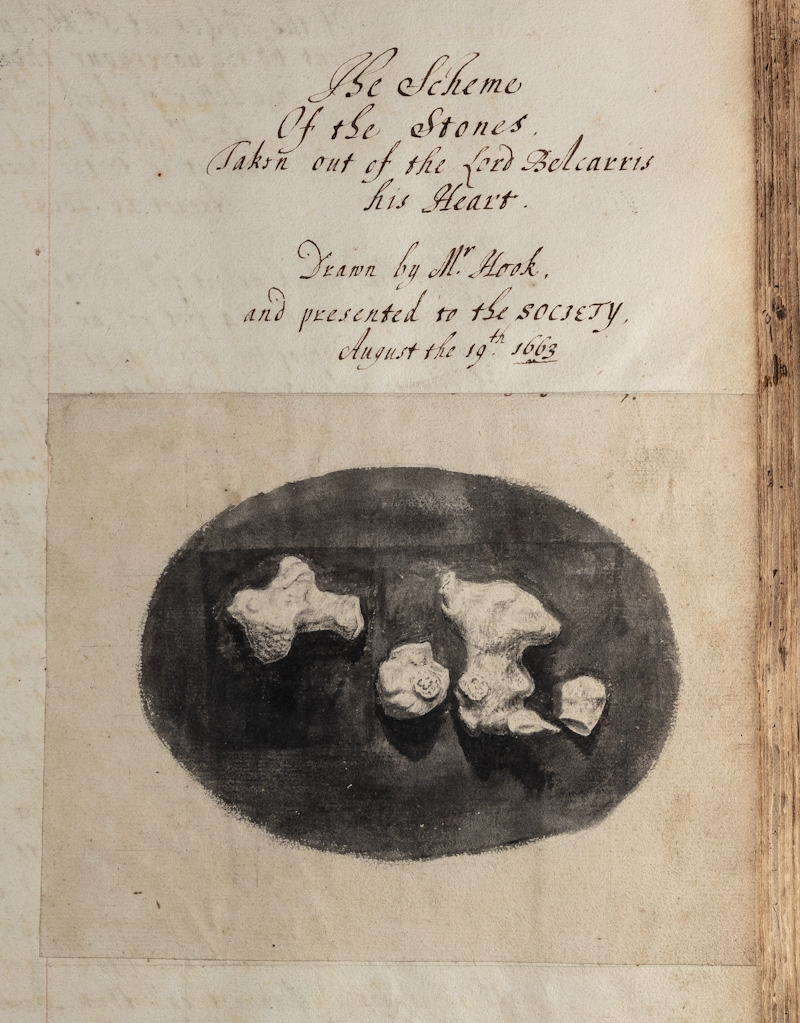

Stones from the heart of the Earl of Balcarres by Robert Hooke, 19th August 1663 (RBO/2i/66)

Stones from the heart of the Earl of Balcarres by Robert Hooke, 19th August 1663 (RBO/2i/66)

On 5 August 1663 Sir Robert Moray presented (apparently not for the first time) stones found in the heart of Charles Lindsay, second Earl of Balcarres, suggesting that a drawing should be made of them; John Wilkins proposed that a cast also be made, and both endeavours were entrusted (as they usually were) to Robert Hooke. These heart stones – likely to have been fragments of bone rather than a result of true lithiasis – led Wilkins to ruminate on other stones of the body and suggest that an experimental surgery be performed on a dog to see ‘whether the stones of the kidnies might be cut with any Success’.

Portrait of John Wilkins (1614-1672) by Mary Beale, ca.1670-72 (RS.9651)

Portrait of John Wilkins (1614-1672) by Mary Beale, ca.1670-72 (RS.9651)

As Wilkins himself lay dying ‘desperately ill of the stone’ in the autumn of 1672 he received a series of bedside visits from his friends at the Royal Society who all sought to save him. One suggested treatment was a solution of amber in spirit of wine with salt of tartar; Founder Fellow Dr Jonathan Goddard advised the application of crushed Spanish fly beetles; propagandist rector Joseph Glanvill recommended what amounted, unhelpfully, to a large dose of calcium.

London physician Walter Needham had been proposed for Royal Society membership by Wilkins in April 1671, and eighteen months later would present the results of his nominee’s autopsy to a group gathered at the Kings Head tavern at Chancery Lane End. According to Hooke ‘There was only found 2 small stones in one kidney and some little gravell in one ureter but neither big enough to stop the water’, and Needham concluded that ‘opiates and other medicines’ provided by Wilkins’s friends had caused his death.

Wilkins had reportedly approached death as a ‘Great experiment’, and in taking his body as their investigative material his friends and colleagues engaged in the epistemic practice of autopsy, a noun coined in the seventeenth century ‘when by our observation, wee get a certaine knowledge of things’ (Popular Errours, 1651). Having taken, as per their motto, nobody’s word for it, the diagnosis of kidney stones was at last confirmed to the Royal Society – as well as their own part in potentially hastening Wilkins’s demise.