Keith Moore looks at the fascinating life of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, writer, traveller and champion of the practice of smallpox inoculation.

Passing the travel section of my local bookshop, it was good to see the letters of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu in print as a paperback, which, naturally, I couldn’t resist. Montagu is a great travel companion – urbane, curious, and amusing. Her literary output is significant, and could have been much more, but for familial sensitivities about cultural norms. The eighteenth century was not sufficiently enlightened to tolerate scandals involving female intellectuals and Fellows of the Royal Society.

Portrait of Lady Wortley Montagu by Jonathan Richardson the Younger, 1725 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Lady Wortley Montagu by Jonathan Richardson the Younger, 1725 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Mary Wortley Montagu (bap.1689-d.1762) was born Lady Mary Pierrepont. In 1712, she married Edward Wortley Montagu (1678-1761) after a long and indecisive courtship on his part, and a farcically inept elopement, worthy of an eighteenth-century comic novelist (Henry Fielding was a cousin). She became a courtier in London, wrote poetry and essays, and was renowned for her beauty; but in 1715 was struck down with smallpox, a disease which had killed her only brother. When, in the following year, she accompanied her husband on a diplomatic mission to the Ottoman Empire, she was primed to recognise the value of inoculation, and ferociously driven to popularise the medical practice once returned to England.

If there is one thing that people know about Montagu, it is her introduction of inoculation to the medical armoury of Europe – and her account of witnessing it is among the most famous of her letters:

‘The smallpox, so fatal and so general among us, is here entirely harmless by the invention of engrafting…There is a set of old women who make it their business to perform the operation…They make parties for this purpose…the old woman comes with a nutshell full of matter of the best sort of smallpox, and asks what veins you please to have opened. She immediately rips open that you offer to her with a large needle (which gives you no more pain that a common scratch) and puts into the vein as much venom as can lie on the head of her needle, and after binds up the little wound with a hollow bit of shell…’

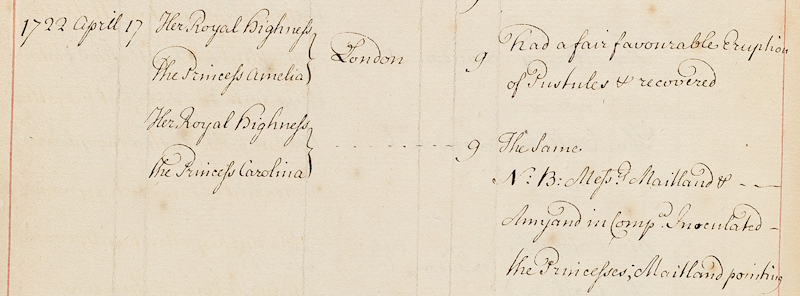

The inoculation of Princess Amelia and Princess Caroline by Charles Maitland and Claude Amyand, 1722 (MS/245, p.4)

The inoculation of Princess Amelia and Princess Caroline by Charles Maitland and Claude Amyand, 1722 (MS/245, p.4)

Montagu spent significant time in the 1720s attempting to get the practice accepted in Britain; and as the Royal Society’s archives show, she began by having her young daughter, also Mary, inoculated, and influenced the Royal family to do the same. That alone would have made her a figure of renown, but it barely scratches the surface of her literary talents and extraordinarily eventful life.

The Embassy letters, originally published posthumously, and semi-anonymously, as ‘Letters of the Right Honorable Lady M--y W--y M--e: written during her travels in Europe, Asia and Africa to persons of distinction…’ (1763) are interesting on many levels. There are the accounts of the towns and cities on her journeyings, dusted with Montagu’s classical learning. Even more fascinating are her thoughts on the relative positions of eighteenth-century women, from her experiences in aristocratic London, and in Islamic Constantinople (Istanbul) and Adrianople (Edirne). She concluded that sequestered and veiled Turkish women had far more control over their everyday lives than their European equivalents; and by adopting Turkish dress, Montagu was herself able to peer into more aspects of local life than her less anonymous British husband. Of course, Mary had many of the attitudes and prejudices of her class – her reports on slaves within the Ottoman Empire are more complacent than anyone today would expect – but she was, perhaps, more open than most to examining a different culture.

Illustration from The present state of the Ottoman Empire by Paul Rycaut, 3rd edition, 1670 (RCN R61721)

Illustration from The present state of the Ottoman Empire by Paul Rycaut, 3rd edition, 1670 (RCN R61721)

The embassy mission was unsuccessful, and Mary’s contribution by far the most significant outcome of the journey. And once published, her letters to her aristocratic friends were recognised as a classic of travel literature from a genuine literary talent. But they almost never saw the light of day. Although Mary herself was on the receiving end of scurrilous lampoons from the Wild West that was the eighteenth-century publishing industry, with a notable vicious feud conducted by Alexander Pope (1688-1744), it would, in the end, come to her rescue – in part. The manuscript of the letters was entrusted to a clergyman, who handed it over to her family. But before he did, the text had been borrowed and surreptitiously copied – their original publication was pirated, therefore, and quickly became a literary sensation.

It was just as well. Mary also kept a private journal for most of her life, which, if the letters are any guide, would likely have joined the canon of some of the great English diaries. It was kept under lock and key, then destroyed during the 1790s in a fit of respectability by her Turkish-born daughter, Mary, Countess of Bute (1718-1794), whom her mother had protected by inoculation all those years before. But why?

One reason may well have been her mother’s well-documented passion for the Newtonian natural philosopher and art collector Francesco Algarotti (1712-1764), who also attracted the attentions of her friend John Hervey (1696-1743), 2nd Baron Hervey. Algarotti was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1736, the year in which Lady Mary met him and fell in love. She would travel to Venice to try to live with him, but the affair, if it was, seems to have been one-sided. Mary would eventually begin more travels, to the conclusion of her adventurous and not always conventional life – what it would be to read her private thoughts on those days.