Vida Milovanovic discovers the stories behind the Royal Society's portraits of Albert Einstein and Max Born.

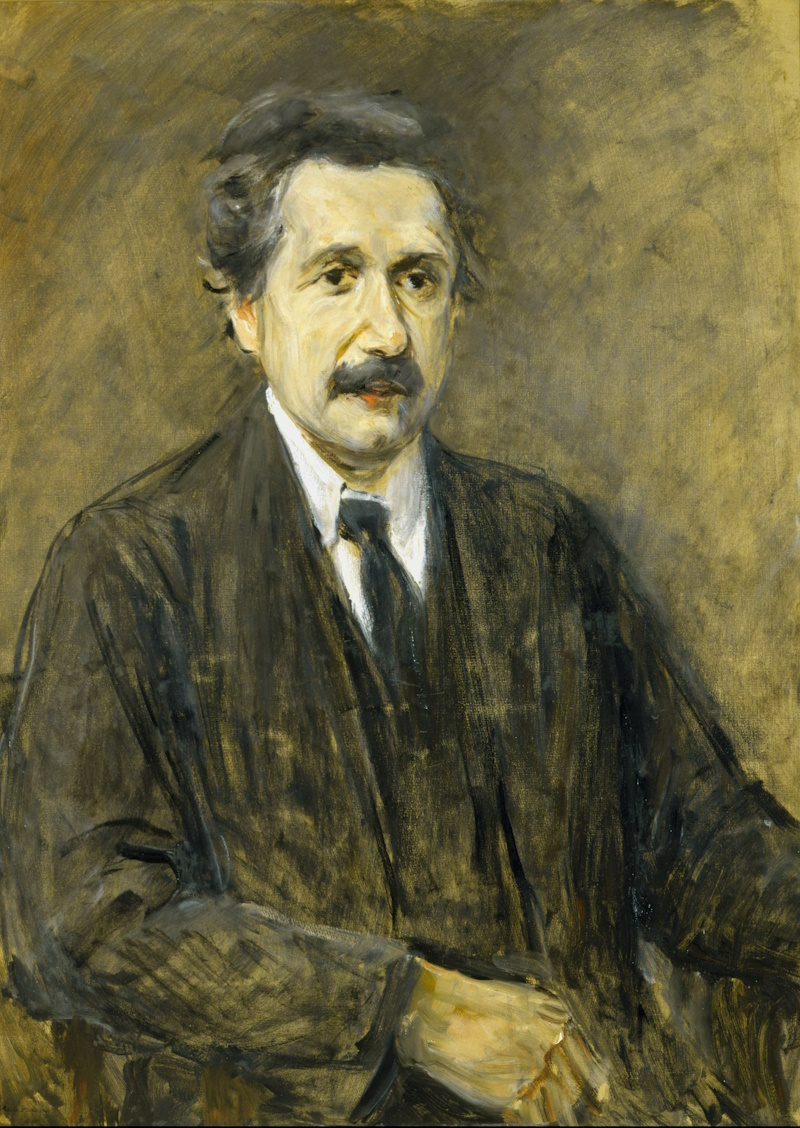

The meeting rooms and corridors of the Royal Society feature a rich and diverse collection of scientific portraits. The one that first grabbed my attention when I started working at the Society was this dynamic and lively rendition of Albert Einstein ForMemRS (1879-1955) by Max Liebermann (1847-1935).

From its composition and subtle tonal shifts to the expressive eyes of the sitter, the painting somehow manages to portray an extraordinary scientist as familiar and approachable. It maybe hints at Liebermann’s evolving style as a painter: he spent the 1870s portraying rural life and the labouring poor, shifting in the 1890s to depictions of the leisured middle classes at coastal resorts, in a lighter and brighter palette.

Einstein’s portrait employs browns and ochres, signalling Liebermann’s early career, but hinting at the new approach with clever impressionistic flourishes such as the single daub of red on the physicist’s lip, bringing dynamism to an otherwise tonally muted image. Creating dimension with thick impasto, Liebermann masterfully rendered Einstein’s likeness – and as I looked into the portrait’s history, it became more interesting yet.

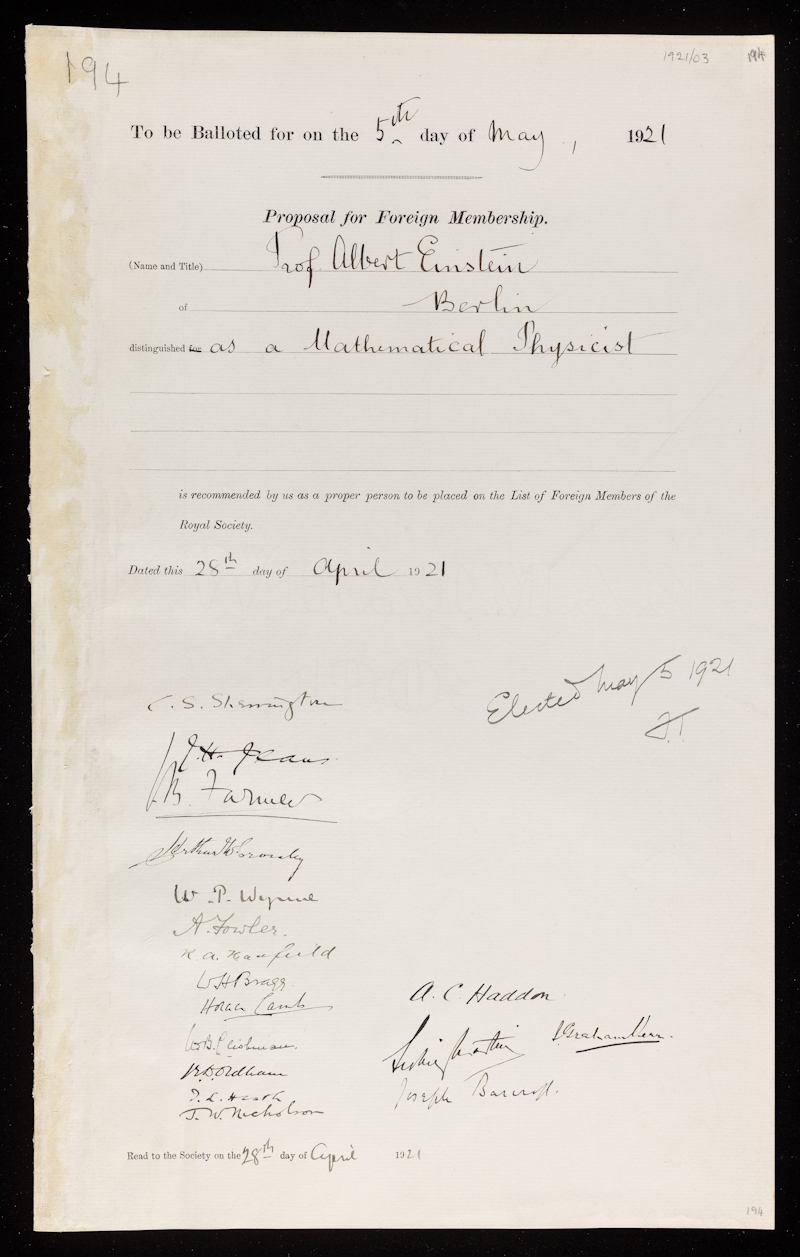

Leiberman painted Albert Einstein as a youthful-looking figure in his early forties, during the initial period of Einstein’s worldwide fame following the Eddington-Dyson 1919 eclipse expeditions, which confirmed his theory of general relativity via observations and measurements during a total solar eclipse. Einstein was elected to the Foreign Membership of the Royal Society in 1921, the same year as he received the Nobel Prize in Physics ‘for his services to Theoretical Physics, and especially for his discovery of the law of the photoelectric effect.’

By 1938, the portrait was owned by Martha Liebermann, the artist’s widow, and was sent to be displayed at the anti-Nazi ‘Exhibition of twentieth century German art’ at the New Burlington Galleries. As reported in a Time Magazine article of 18 July 1938:

‘Last week in London memories … were powerfully stirred by an exhibition of 20th Century German Art ... shown was the work of mild, good-natured Max Liebermann, who died three years ago after his work was banned ... because he was Jewish.’

Contemporary press coverage captured the very real threat to the survival of the painting, should it return to Germany. In August 1938, the New York Times reported that ‘There is every hope that Max Liebermann’s portrait of Professor Albert Einstein ... will be purchased here and so prevented from going to Germany where it would stand a good chance of being destroyed.’

Correspondence within the Royal Society Modern Domestic Archives (MDA/G/3/1) shows that contributions for most of the sum required to purchase the portrait for the Royal Society were made by Sir Victor Sassoon (1881-1961) and others. The purchase price was paid to Martha Liebermann’s agent, who organised the exhibition, but there is no proof that Martha Liebermann actually received the purchase price herself due to the circumstances of her persecution in Germany.

At the time of acquisition, the Royal Society was based at Burlington House, where the portrait remained until the Society moved to its current premises on Carlton House Terrace in 1967. In a curious twist, the Royal Society’s new home had been the German Embassy until 1939. The portrait now hangs in a prominent position on the first floor, seen every day by many visitors to the Society. I wonder whether one of the paintings and busts of Hitler known to have been on show in the 1930s Embassy once occupied that same spot? Poetic justice if so.

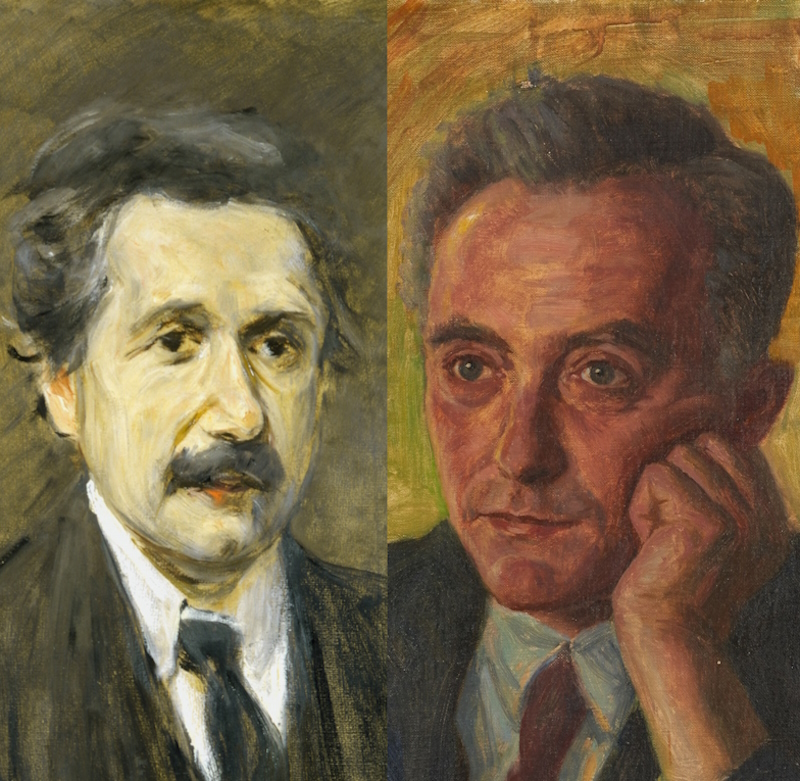

It’s interesting to compare our Einstein portrait with that of Max Born FRS (1882-1970), another famous Nobel Prize-winning physicist of Jewish descent, and a lifelong friend of Einstein’s. Their forty-year correspondence, published as the Born-Einstein letters, is a meeting of two brilliant and cultured minds in the most turbulent of centuries. The Born portrait was commissioned from artist Hermann Hirsch (1861-1934), painted in 1931, brought to the United Kingdom by the Born family, and finally presented to the Society in 2015 by the sitter’s son Gustav Born FRS (1921-2018).

The Royal Society is one of the few lucky owners of a piece by Hirsch. His art is largely privately owned, with the only major public collection of his works held in the Städtisches Museum Göttingen, plus a handful in the Virginia Holocaust Museum.

Mirroring the experience of most European Jews at the time, Hirsch experienced the steady rise of antisemitism in Germany. By 1933 he was one of the last few Jews in Bremke, a small village near Göttingen in Lower Saxony. His friends began to distance themselves from him, and with hostility towards Jews becoming commonplace, he even faced an attack on his home. His family escaped to other parts of the world leaving him no choice but to leave Bremke for Göttingen, where he moved in with a Jewish family. The dire situation he found himself in tragically culminated in his suicide on 1 March 1934, the Göttinger Zeitung lamenting that ‘A nice, honest, and pure human spirit passed with him – he broke due to the harshness on his dignity.’

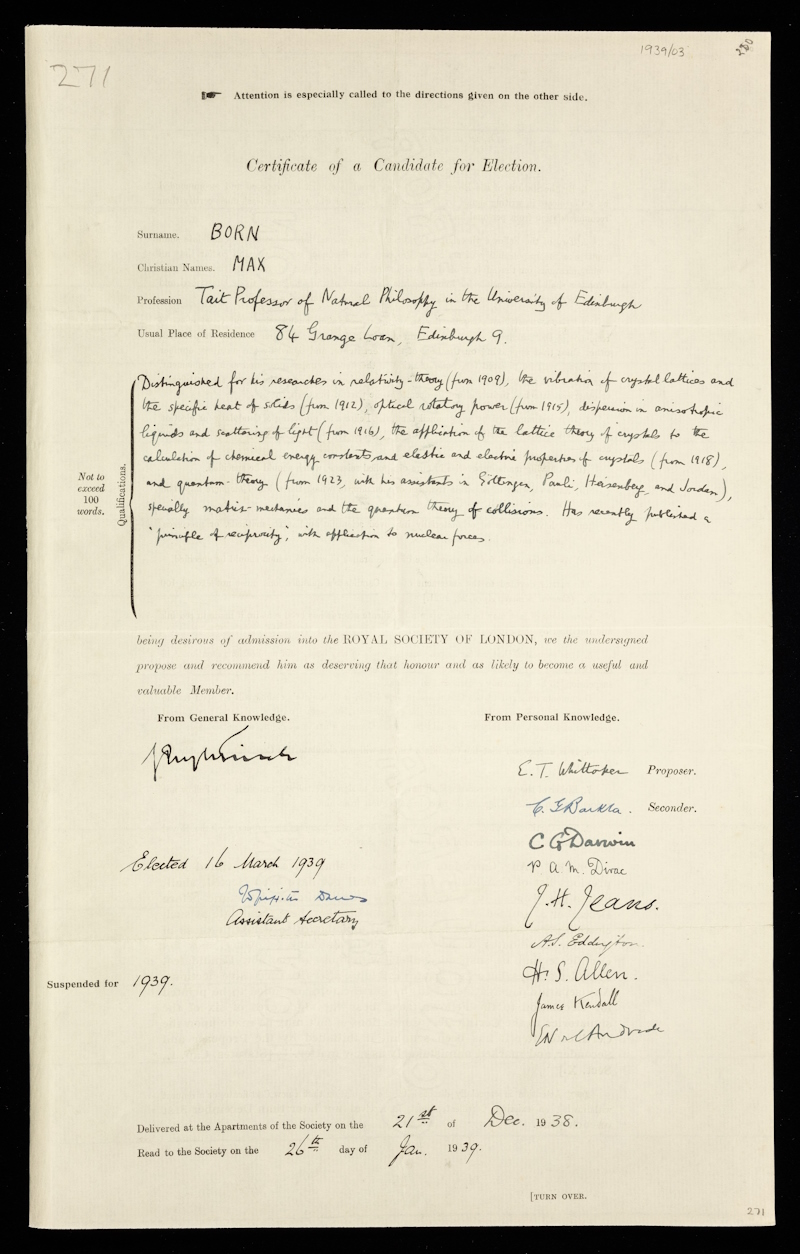

Hirsch’s sitter Max Born famously coined the term ‘quantum mechanics’ in 1924, and shared the 1954 Nobel Prize in Physics for ‘fundamental research in quantum mechanics, especially in the statistical interpretation of the wave function’. He was first nominated for the Nobel as early as 1928 by none other than Einstein, whom Born had previously defended against critics of the theory of relativity, delivering supportive speeches in 1919. Born was also awarded the Royal Society’s Hughes Medal in 1950 ‘for his contributions to theoretical physics in general and to the development of quantum mechanics in particular’.

Born was a physics professor in Frankfurt-am-Main from 1919 to 1921, then in Göttingen until 1933. After being subjected to new discriminatory legislation which dismissed all Jews from academic positions in Germany, he left for England in April 1934. Here, he was appointed to a temporary lectureship at Cambridge, becoming Tait Professor of Natural Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh in 1936.

What began as a quick personal enquiry into a painting ended in the discovery of a multi-layered story of defiance and survival. It links together two artists whose work survived against great odds, to celebrate a friendship between two of the most eminent scientists of the twentieth century.