Dr Ferenc Jordán, guest editor of the latest Philosophical Transactions B issue, tells us about the background and content of the new theme issue.

In ecological research, different kinds of interactions among organisms are modelled by networks. These various network types are traditionally studied in separation, by ethologists, community ecologists and landscape ecologists. However, all of these connections concern the same individuals that can socialize, eat and be eaten or migrate, being involved in all kinds of processes in parallel. In a new theme issue of Philosophical Transactions B, a broad range of researchers present examples for how to connect various networks, considering several processes in parallel. Studying multiple networks is highly beneficial, especially for better understanding socio-ecological systems and challenges across scales. In this blog post, Guest Editor Dr Ferenc Jordán (University of Parma) introduces the topic.

Thanks to technological development and new data, in the past few decades our knowledge on interactions and networks has greatly expanded. We have been able to construct food webs and other kinds of networks representing inter-specific interactions in multi-species ecological communities, including marine, freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems. There are a growing number of known social networks for animal groups of various species, ranging from ants to primates and from meerkats to water striders. We use network models also for the spatial configuration of habitat patches connected by ecological corridors, for birds and carabids and for agricultural fields and tropical forests. All these networks help us to look at nature from a systems perspective. One may pose novel questions about centrality, feedbacks, indirect effects and modular architecture. These are not only methodological but also conceptual advancements. Our new theme issue brings together 18 new papers providing new approaches to this field.

In the past, great research had already been done using concepts of network design and system structure. In ecology, simple feedback loops among organisms helped to understand their relationship. However, looking only at one or even two interacting species may not be enough. A famous example is the ‘Utricularia’s secret’, presented by Professor Robert Ulanowicz, discussing a three-species positive loop, where the population dynamics of any species could not be understood without looking also at the other two. In landscape ecology, now we speak routinely about linear landscape elements, knowing their structure and consequences, and the properties of linearity means much more to us than before. Similarly, the concept of source and sink populations refers to directed networks of spatial connections – with so many implications. The youngest examples surely come from animal social network analysis: famous concepts of sociology, including cliques and clusters, make much more sense now to animal behaviour researchers who have been traditionally mostly interested in linear pecking orders beyond group size.

While we can understand the mentioned ecological systems, social groups, communities and landscapes better, we can also realize that these systems are hierarchically embedded. In addition to interactions among similar agents (connecting, for example, two species), there are interactions between different kinds of agents, too. For example, the dynamics of a predator-prey connection depends also on the social organization of the prey. The interaction between two species is connected to the internal interactive system of one of the species. From the viewpoint of hierarchical organization of life, these are horizontal and vertical connections, respectively. Horizontal connections, such as trophic links in community ecology, social links in ethology and spatial connections in landscape ecology, are traditionally better studied, fitting well within disciplinary boundaries. But we need to look beyond this and break down the boundaries created by research being done in different departments, within different research cultures. Linking a predator-prey effect to the social organization of the prey is out of the box in an epistemological sense. This is why this cross-disciplinary approach is so exciting and useful.

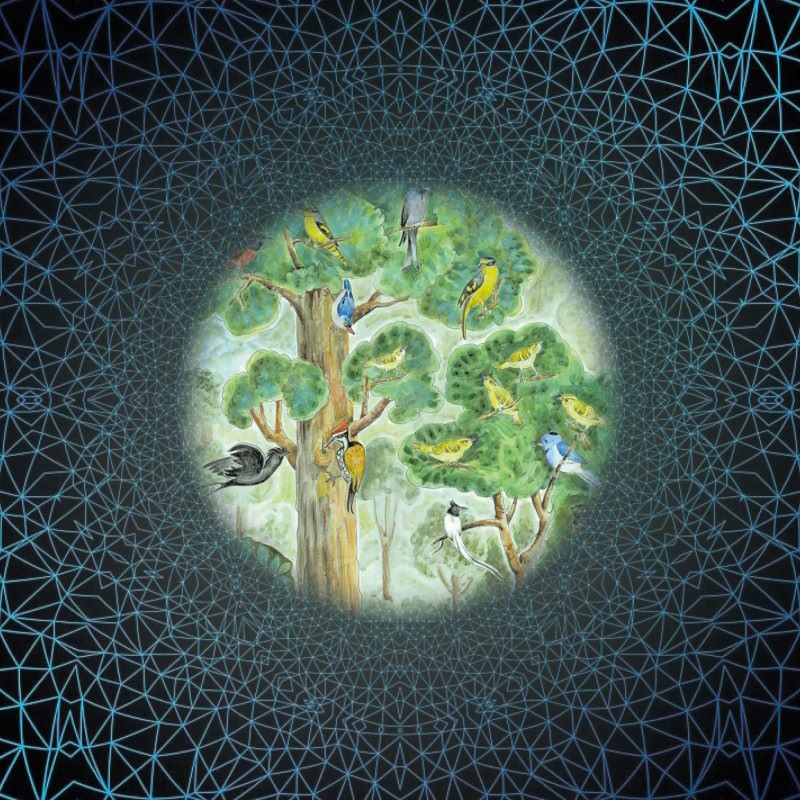

We could dramatically expand our systems perspective by connecting different kinds of connections. Trophic links can be connected to spatial connections and social interactions, as the probably most important and currently most feasible way to build networks of networks. There are many examples for this line of interest and this volume presents a number of excellent examples related to this. One should not always expect large networks in these papers, but complexity is guaranteed by the multiplicity of either players and connections among them, or both. We focus on mechanisms and conceptual challenges instead of big data and computational novelties. But the direction of future research seems to be like this: integrating several dimensions of connections. The meeting point is often the individual organism: it can eat and be eaten, it can move to another location and it can socialize or become isolated in the group. All these interactions and processes are naturally connected at the probably most neglected level of biological organization, at the level of the organism.

In a few papers, the authors make one step beyond the above: the human component is also included. This always increases complexity (sometimes in an unpleasant way) but the challenge is important: today we speak about and need to understand socio-ecological systems almost everywhere. Pristine natural systems are vanishing all around us and, along with this, we are losing novel connections, structures and functions. But also our own role can be better understood (and engineered?) if we have a more developed, hierarchical view on the rest of the biosphere.

Visit our website to read more content from Philosophical Transactions B, or to find out how you can become a Guest Editor for the journal.

Image: Centre: painting by Rangu Narayan of a mixed-species bird flock in a tropical forest of the Western Ghats, India. Outside: network by geralt/Pixabay. Composition created by Silvia Garante, EFT GIS and graphics, Parma, Italy.