A new J. R. Soc. Interface paper examines the wider possible social effects of violent conflict in human prehistory, specifically in terms of population distribution. We spoke to the lead author, Dr Dániel Kondor at Complexity Science Hub Vienna, to find out more.

Tell us about your study

The main objective of our study is to gain a more complete understanding of inter-group conflicts in their wider context in prehistory. More specifically, our focus is on Europe around 5000-9000 years ago, a time when agriculture was widely practised, but without persistent large-scale political organization.

In public debates, questions about conflicts and violence in prehistory are still often presented and perceived in dualistic terms, as either a ‘war of all men against all men’ which was popularised by Thomas Hobbes or a view of prehistoric humans as ‘noble savages’ which was put forward by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The latter theory suggests that humans, in their ‘natural state’, were essentially free and innocent.

In contrast, scholarly research recognises diverse possibilities in human behaviour at both the individual and group level and takes a more nuanced approach to the question of conflict as well. The focus is on collecting and interpreting evidence for or against conflicts, potential causes and consequences, and the role of environmental and social factors. However, due to the ambiguity of evidence, it is still difficult to reliably establish such interpretations, even in well-researched regions.

In our work, we use computational modelling and focus on possible consequences of group-level conflicts. We demonstrate that these can include wide-ranging changes in the spatial configuration of settlements and regional population numbers due to people fleeing from and avoiding conflict areas. We validate our model with a statistical analysis using a database of archaeological finds in Europe, and show that conflicts and their wider, indirect effects could plausibly explain large-scale and long-term population dynamics of this period.

What led you to research this topic?

In the past decades, a growing amount of evidence has accumulated suggesting large-scale population fluctuations in prehistoric Europe. These include cases where large regions saw significantly reduced human activity or even complete abandonment for extended periods of time. Finding the causes of such declines presents a challenge, and so far environmental explanations (such as proposed changes in climate or soil conditions) have been challenged, especially in light of growing evidence for the resilience of early farmers facing environments which were often unpredictable. As such, explanations stressing social interactions are favoured by many; however, it is not easy to conceive how large-scale patterns would arise from mostly local interactions among people living in small independent groups.

Our previous modelling work has already shown that conflicts, and specifically changing cultural attitudes to conflict (interpreted as alternating periods of social integration and disintegration) can generate large-scale and long-term patterns, including the substantial and prolonged population declines observed in the archaeological record. However, our earlier models still treated conflicts in a highly abstract way. In the current work, we were able to incorporate a wider set of possible effects of conflicts beyond battle casualties, including adaptations to avoid conflicts, and have shown that these provide more plausible explanation for large-scale regional population declines. Specifically, we find that such "indirect" effects, such as abandonment and avoidance of conflict areas, are key to reproduce realistic population trajectories that are also consistent with our knowledge about conflicts among small groups.

Are there specific takeaways that policymakers and academics can apply to modern day challenges?

Our research shows that human societies have likely formed complex, interconnected systems since prehistory, even without actively creating large-scale political or economic organizational structures. In our simulation model, all groups are independent, and interactions happen on local scales; however, effects eventually propagate to much larger areas, including groups who do not have a role in the original initiation of conflicts. More generally, this demonstrates that local interactions and local connections can lead to global effects, which potentially could only be managed by global-scale action. We believe that there are many similar issues in the modern world where local interactions contribute to global dynamics, and thus necessitate global-scale cooperation to overcome.

How was your experience publishing in J. R. Soc. Interface?

We had quite a positive experience: the submission process was convenient, and we got positive and constructive reviews in a timely manner.

To take a look at more work that applies modelling to innovative topics and to find out how to submit, check out our website.

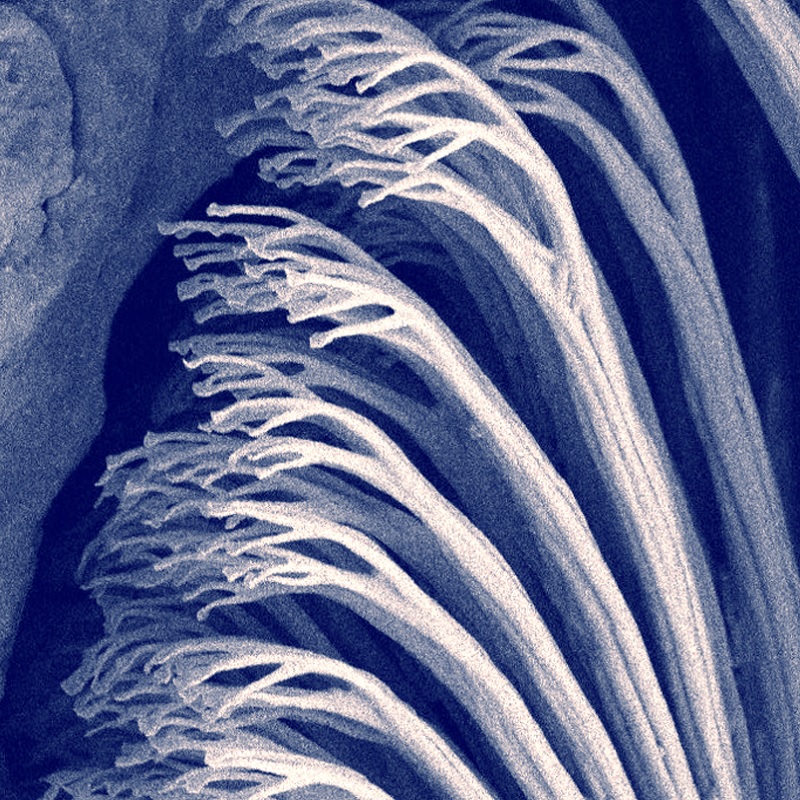

Image credit: Enclosed hill-top site of Kapellenberg, Hofheim, Germany. Visualisation of the settlement around 3700 BCE (Copyright: Magistrat der Stadt Hofheim; LEIZA-Leibniz-Zentrum für Archäologie, Architectura Virtualis 2020: http://www.leiza.de/kapellenberg).