For Black History Month, Ankita Anirban shares how Earl Shaw combined his research in laser physics whilst advocating for the rights of Black researchers and inspiring future generations of scientists.

In 1969, Earl Shaw graduated with a PhD in physics from the University of California, Berkeley and became the first African-American PhD physicist to be hired by Bell Laboratories. There, he co-invented the spin-flip Raman tunable laser and built a free electron laser that could reach into the far infrared spectrum and probe the inner workings of biochemical processes.

“You have to go to Bell Labs” his PhD advisor said, when Earl got the job offer. In the 1960s, Bell Labs was the place to be – home to the best and brightest scientific minds of the 20th century. Now it was Earl’s turn to enter this elite network of scientists. He joined the laser physics research group, headed by Indian physicist, C. Kumar N. Patel. Laser science had really taken off in the previous decade, and had piqued Earl’s interest during his PhD research.

Lasers come in different forms – they can be made from crystals like ruby, or gases like carbon dioxide. At Bell Labs, carbon dioxide lasers were the focus of research, and they emitted infrared light. The problem facing the team was how to change the frequency of this light. The experiment was hard. Then, one night, a clear peak appeared in their data. This was the signal that it had worked: the first sign of a tunable, infrared laser.

Science and social justice

“[Earl] was energetic… I just remember how exuberant he was, how he loved talking about science all the time,” Evelynn Hammonds told me, while recalling her time as a Bell Labs summer student in the 1970s.

Over two decades at Bell Labs, Earl became a pillar of the community. He not only brought his energy into his science, but also into advocating for the rights of Black employees and into recruiting the next generation of Black scientists. With little interest in joining the ranks of corporate management, Earl focussed on his scientific work, but always with a strong social conscience. When talking about racial integration at the labs, Earl put it like this: “I was very very involved – not in memo writing – but I knew everybody, so I would go to people, who were in principle not inclined [towards racial integration], get in their office and present my case.”

Earl’s involvement in social justice blossomed in his time as a PhD student in Berkeley, California in the 1960s. Against the backdrop of the Civil Rights movement and the Vietnam war, he soon got involved in student politics. Berkeley was also where Earl found his identity as a physicist. He would spend hours reading old physics papers in the library, trying to get into the minds of physicists, and understand what made them tick. “I really went into it rebelliously”, Earl recalled many years later, in an interview with journalist, Dick Russell. He was trying to find other ways of articulating classic theorems. In the end, he realised that it didn’t matter how they were formulated – the fact that they worked was enough, and what was important was to keep going forward.

A lifetime project

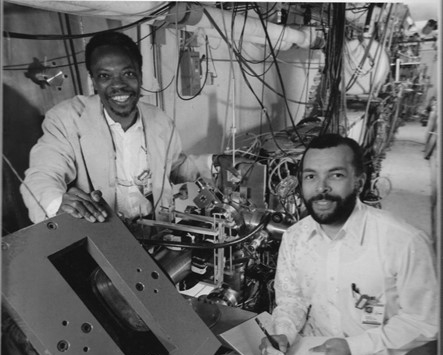

After the success of the tunable laser experiment, Earl turned to a bigger project; to build a free-electron laser. Ordinary lasers rely on the movement of electrons within an atom to generate light. A free-electron laser uses a bunch of electrons that are not bound to atoms: this means a lot more flexibility in terms of the type of light they can generate. Huge, and very complicated to build, they are usually hosted in large, shared facilities. During the 1980s, Earl, along with his support engineer, Rob Chichester, developed and built a free-electron laser at Bell Labs (pictured) – one that could reach into the far infrared spectrum, which is the frequency at which proteins vibrate.

In 1991, Earl moved to Rutgers University in New Jersey, taking the laser with him. Here, he turned his attention to using the laser to study biological processes. The academic environment also gave him a chance to interact more closely with students. Throughout his career he mentored and inspired multiple generations of Black scientists. As he told Russell in the 1990s, “I’ve been involved with so many young physicists. If there’s a Black physicist in the country, I know him.”

Image caption: Earl Shaw and Rob Chichester at Bell Labs with their free-electron laser. Circa 1990.

This post has been written as part of the Reclaiming narratives: ScienceWrite blog series which highlights the lives and achievements of extraordinary scientists from minoritised groups.