Jon Bushell reports on the papers of the physicist and glaciologist John Nye FRS, recently acquired by the Royal Society Library.

The Royal Society’s archival collections continue to grow each year, as we receive donations from more recent Fellows and their families. I’m currently hard at work cataloguing a set of papers relating to John Frederick Nye, a physicist who spent most of his career at Bristol University and had a particular interest in glaciers.

Photograph of John Nye, taken upon his election to the Royal Society in 1976 © Godfrey Argent (IM/GA/JGRS/7971)

Photograph of John Nye, taken upon his election to the Royal Society in 1976 © Godfrey Argent (IM/GA/JGRS/7971)

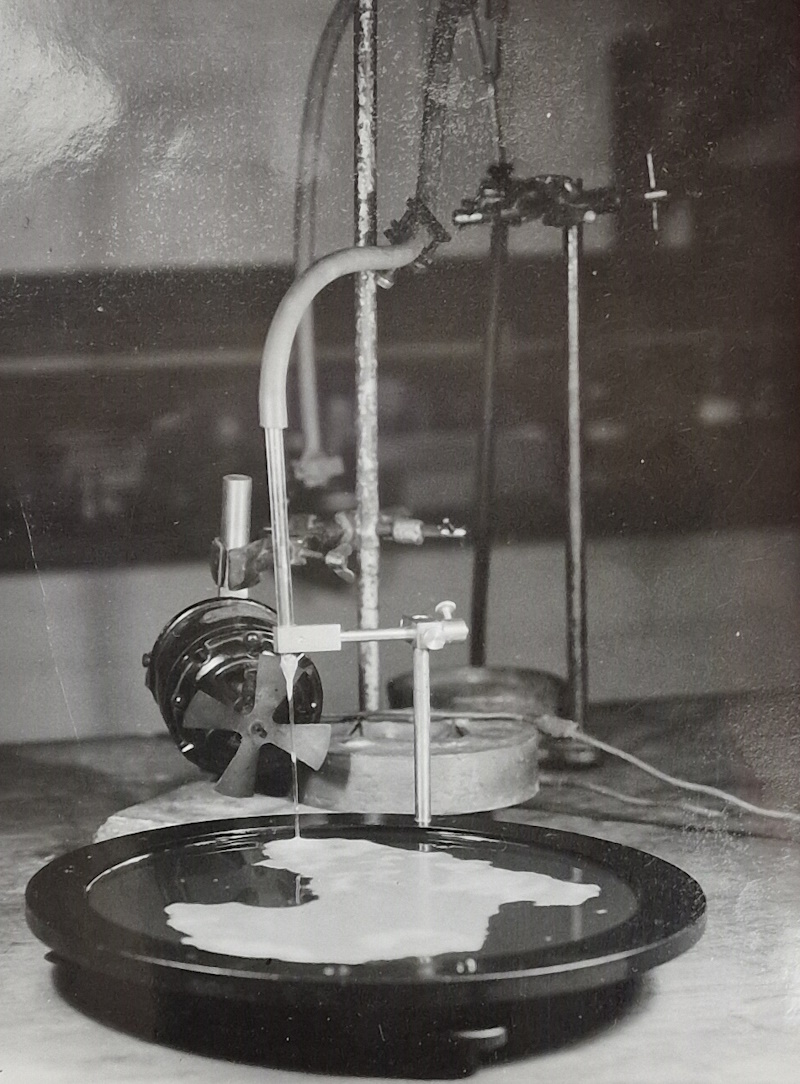

Nye’s early research focused on the properties of crystals. His PhD thesis covered dislocations: defects in crystals where the arrangement of atoms changes. His work led to an important collaboration with Sir Lawrence Bragg at the Royal Institution, in which the pair used soap bubbles to develop a two-dimensional representation of a crystal lattice. This ‘bubble model’ helped scientists visualise how individual atoms are responsible for the deformation of solid objects, such as when a piece of metal is bent. Their work was published in the Proceedings of the Royal Society A in 1947, and a film was made by the Royal Institution.

The equipment used by Bragg and Nye to create the floating bubble raft (this, and all subsequent pictures, are from the papers of John Nye in the Royal Society Library)

The equipment used by Bragg and Nye to create the floating bubble raft (this, and all subsequent pictures, are from the papers of John Nye in the Royal Society Library)

Nye’s interest in glaciers was sparked by his PhD supervisor, Egon Orowan, who had a background in metallurgy and was interested in the long-standing problem of how glaciers moved. The prevailing theory in the 1940s was that they flowed like a thick liquid under pressure. In particular, it was thought that an effect known as extrusion flow was occurring, where ice deep in a glacier was squeezed by the pressure above it, pushing the base of the glacier downhill and dragging the ice on top along with it.

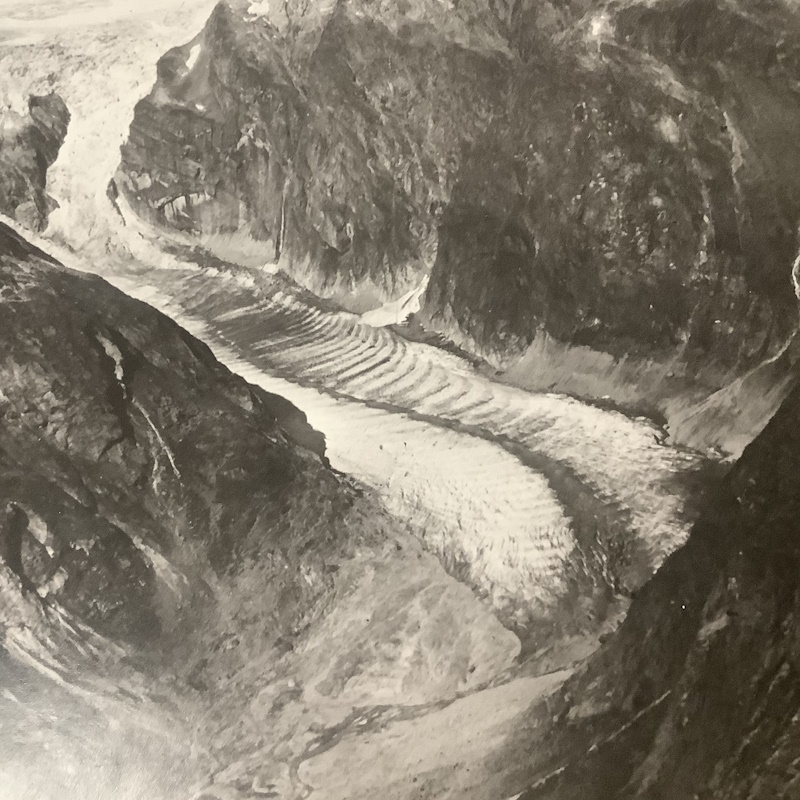

Orowan considered an alternative model which presented glacier movement as the result of plastic deformation instead. This caught Nye’s attention, as there was considerable overlap with the work he’d been doing on crystal deformation. He believed he could improve upon Orowan’s initial idea to create a much more accurate model of glacier flow. Soon enough, he joined Max Perutz and John Glen on an expedition to the Jungfraufirn glacier in Switzerland.

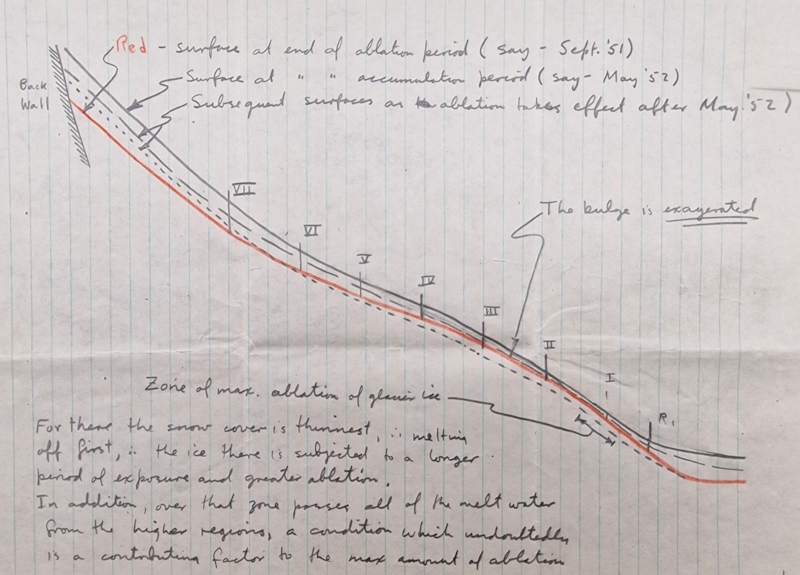

Diagram drawn by Glen in 1952, showing accumulation and ablation of Skauthöe glacier in Norway

Diagram drawn by Glen in 1952, showing accumulation and ablation of Skauthöe glacier in Norway

Perutz was conducting an experiment in which he had melted a metal pipe into the glacier vertically. By returning each year to measure the change in its angle, it was possible to determine the velocity at different depths of the glacier. The results, published in Proceedings of the Royal Society A in 1952, showed that glaciers moved more slowly at depth, not faster. This was more evidence in support of Orowan’s plastic flow hypothesis. That same year, Glen published the results of his laboratory experiments on the deformation of ice under stress in the Journal of Glaciology. Nye got to work to synthesise these ideas into a comprehensive glacier flow model.

Nye’s paper, ‘The Mechanics of Glacier Flow’, was published in the Journal of Glaciology in 1952. In it, he provided calculations for the laminar flow of ice under gravity, which backed up the results of Perutz’s pipe experiment. He also refined Orowan’s approach, calculating the effect of deformation throughout the glacier rather than only at the base, and showing how drag from the valley bottom and sides would slow a glacier down as it moved along its channel. Finally, he considered how faults and crevasses could form in the glacier as it moved.

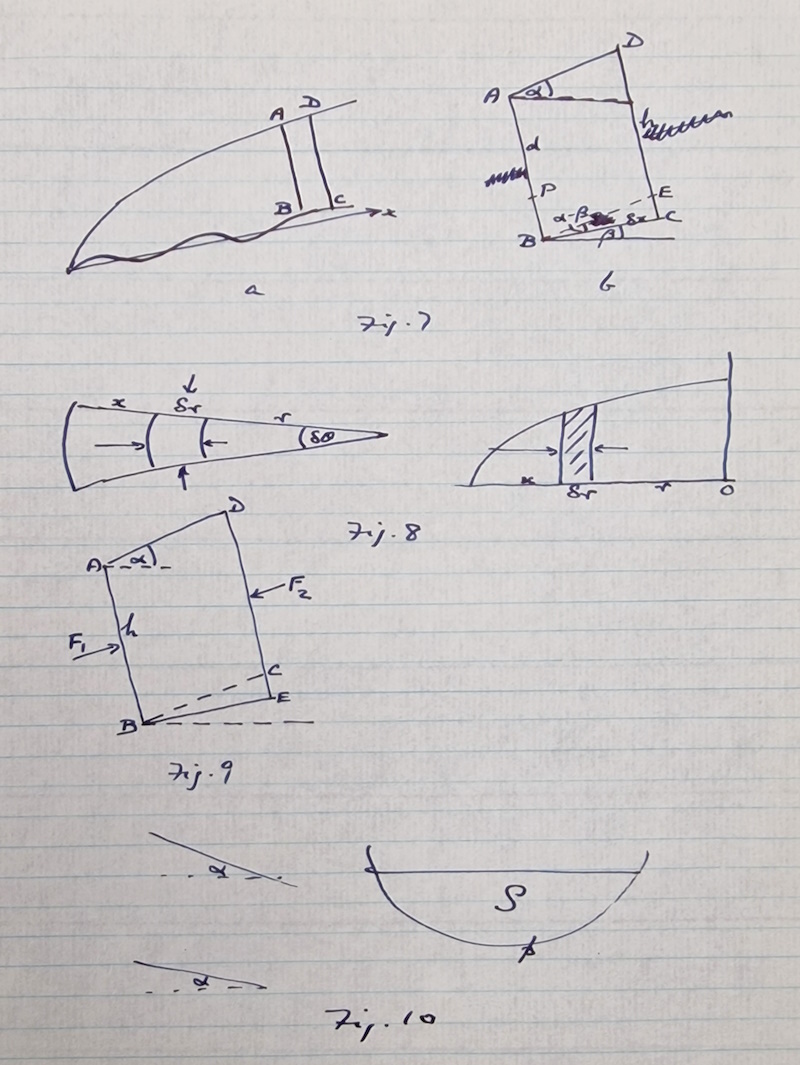

Diagrams drawn by Nye in 1964, for a book on glacier flow that was never published

Diagrams drawn by Nye in 1964, for a book on glacier flow that was never published

It was an important paper. By unifying the various theories and experimental results from his contemporaries, Nye’s model provided a solid foundation for modern glaciology, though it wasn’t without its critics. His paper effectively disproved free extrusion flow in glaciers, a theory that had numerous supporters at the time. One of those was Joel Fisher, a mountaineer and glaciologist who had previously served as president of the American Alpine Club. His critique of Nye’s paper was also published in the Journal of Glaciology, along with Nye’s own rebuttal. There was further correspondence between the pair as Fisher tried unsuccessfully to convince Nye that his model was incorrect.

Extract of a letter from Fisher to Nye, dated 21 May 1952

Extract of a letter from Fisher to Nye, dated 21 May 1952

Following publication, Nye spent the following two decades working very successfully on glaciology. He continued to collaborate with John Glen, and the pair were heavily involved with Cambridge University’s expeditions to the Austerdalsbreen glacier in Norway. These were annual research visits initially led by Vaughan Lewis, with a small army of Cambridge undergraduates in tow to carry out the digging and heavy lifting.

Members of the 1955 Cambridge Austerdalsbreen Expedition at work on the glacier

Members of the 1955 Cambridge Austerdalsbreen Expedition at work on the glacier

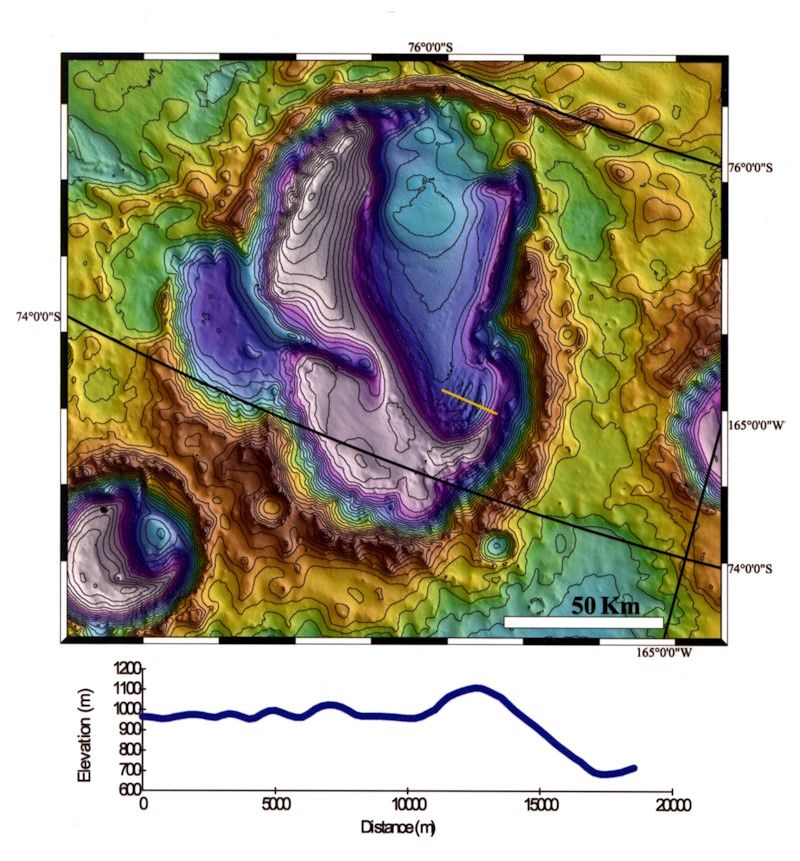

Nye found the field experience valuable, but he strongly believed that it wasn’t necessary to study glaciers in person, providing you had enough data available. Much later in his career he even applied his modelling to the Martian polar ice caps. His preference for calculation over fieldwork might explain his decision to move away from glaciology in the 1970s. Nye helped develop early methods for using radio echo sounding to determine the thickness of ice sheets, and in the process became much more interested in light and wave forms. Nevertheless, he maintained a watching brief on the field for the rest of his career. Topographical map of a region near the south pole of Mars, showing features potentially created by flowing ice, sent to Nye by Shane Byrne in 2003

Topographical map of a region near the south pole of Mars, showing features potentially created by flowing ice, sent to Nye by Shane Byrne in 2003

There’s much more in Nye’s papers we’re still cataloguing, and we hope to make these records searchable in our online catalogue in the next few weeks. There are drafts and research material for his published and unpublished works, as well as the many speaking engagements he undertook throughout his career. His international travel is also represented, including visits to the USSR in the 1980s. There are several 16mm films of both the bubble model and glaciers, plus an extensive collection of photographs. All in all, a rather Nye-ice collection of papers, I think you’ll agree.