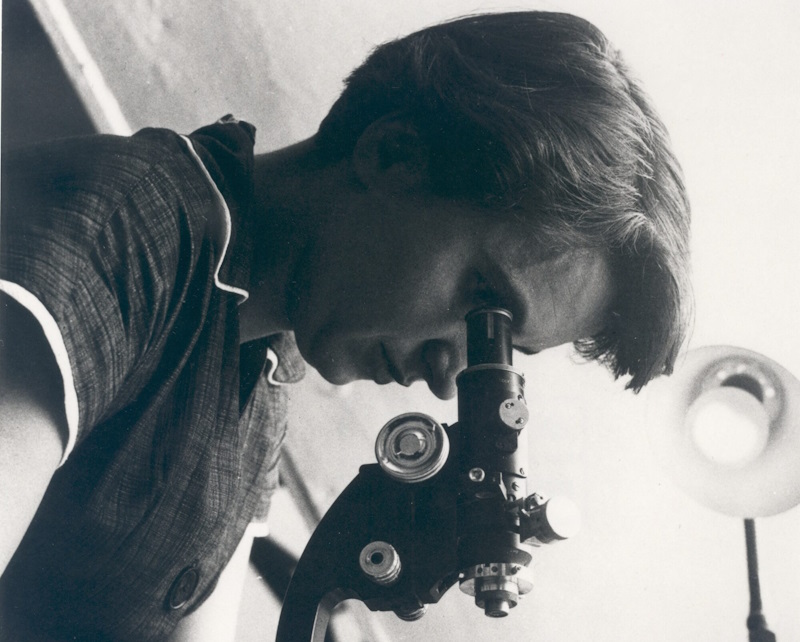

Rosalind Franklin never lived to see the full impact of her discoveries. She didn’t witness how her work on DNA would revolutionise biology, nor did she witness the impact she would have in encouraging women researchers in science. For International Women’s Day, Liz Sockett FRS, Chair of the Royal Society’s Rosalind Franklin Award committee, and Isabelle Moss, Royal Society Diversity and Inclusion Officer, reflect on Franklin’s enduring legacy.

Best known for providing key X-ray diffraction evidence, along with her student Raymond Gosling, for the structure of DNA, Rosalind Franklin’s work was crucial for proposing and supporting the double helix model. In 1962, several years after Franklin’s death, Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins were awarded the Nobel Prize for their work on DNA and no reference was made to Franklin’s significant contribution to this discovery.

Franklin died tragically young from cancer, but the achievements she made in her career were nothing short of remarkable. In addition to her work on DNA, she also used X-ray crystallography techniques to investigate and publish a wide range of molecular structures including RNA, viruses (such as the tobacco mosaic virus), coal and graphite. Franklin’s gravestone reads, “Her work on viruses was of lasting benefit to mankind.” Perhaps it is not altogether unsurprising that her contributions to DNA structure were not recognised until long after her death, considering her commemoration reflects the biases of her time through the traditional but gender biased wording “mankind.”

Her long years and hours of meticulous and repeated experimental work, some of it during ill health, and with both the stimulus and the pressure of ongoing theory developments in the field, is familiar to many scientists. It is right to remember her and her devoted research.

In 2003, the Royal Society launched the Rosalind Franklin Award and Lecture, to celebrate the legacy of Franklin’s contributions, as a scientist, unsung hero and touchstone that she has evolved to be for women in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM). The award is given for a project, by an early-career scientist, to promote women in STEM by an individual with an established track record of very high standing in any area of STEM. All winners are awarded a £40,000 grant, £30,000 of which should be spent on a project to support women in STEM and £10,000 to support their research in a way that they choose. In addition to this, winners are invited to present a lecture at the Royal Society providing an overview of their research and plans to support women in STEM. Since its inception in 2003, the award has supported numerous projects aimed at increasing diversity and inclusion in scientific research.

In its first year, the award received 68 nominations; clear evidence of the importance of this topic at a time when women made up less than 9% of the UK’s full time and part-time professors in science. The inaugural award was given to Professor Susan Gibson of King’s College London, for her research on organometallic reagents. Gibson used the award to convene women synthetic chemists from around the world to the UK with the aim of encouraging younger researchers to pursue academic or industrial careers.

Today, 21 years later, we have the pleasure of running the Rosalind Franklin award committee. And we still receive 15-30 very high-quality nominations a year. It’s fascinating to read about nominees’ incredible achievements, both in their scientific pursuits and in their efforts to promote diversity in STEM. In research, achievements are too often measured solely by publication rate and number of citations, which leaves contributions to improving research culture overlooked. Therefore, initiatives such as the Rosalind Franklin award are an important part of addressing this balance by recognising the contributions of individual scientists to improving diversity and inclusion in STEM.

In 2024 Dr Jess Wade from Imperial College won the award and gave a captivating talk explaining both her research in the chirality of molecules and her outstanding initiatives to promote and recognise the careers of women scientists. Dr Jess Wade’s lecture and those of others recent winners including Professor Julia Gog and Professor Sarah-Jayne Blakemore FRS are available from the Royal Society’s YouTube channel. It is clear that the award has recognised several early-career scientists who have gone on to be leaders in national and world science, including Professor Dame Ottoline Leyser FRS (who received both Rosalind Franklin and later Croonian Awards), maybe as Franklin might have done, had she lived.

Rosalind Franklin’s legacy continues to inspire generations of women to pursue careers in STEM. As we recognise her contributions and those who have followed in her path, it’s clear that building a more inclusive and equitable future in science remains essential. There’s no telling how many talented individuals are yet to be recognised.