The Royal Society declared that women were eligible for election to the Fellowship in 1922 but, as Keith Moore notes, a fallow period persisted for another two decades.

In looking over papers relating to the history of women scientists at the Royal Society, I’m always struck by that strange fallow period between 1922 (when women were declared to be eligible for Fellowship), and the efforts to elect Kathleen Lonsdale and Marjory Stephenson, which came to fruition in 1945. It wasn’t as if female scientists were inactive within the Society’s areas of influence during those years, far from it. And there were people looking to turn things around.

By 1919, equal opportunities legislation had, in theory, made women able to claim parity with men in some spheres, although voting rights remained an issue until 1928. For the Royal Society, it meant revising institutional thinking; and in 1922 a Council-requested legal opinion overturned the barriers which had led to the rejection of Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923) as a candidate for election twenty years earlier.

1919 also marked the creation of the Women’s Engineering Society, and its first Secretary, Caroline Haslett (1895-1957), was quick to broach the topic of women’s Fellowship of the Royal Society. Annoyingly, her original letters do not seem to have survived in the collection, but we do have copies of the secretarial responses, including by James Jeans, who replied that women were indeed eligible, provided that their scientific attainments were of the requisite standard.

Hertha Ayrton in her laboratory (frontispiece of Evelyn Sharp’s 1926 memoir)

Hertha Ayrton in her laboratory (frontispiece of Evelyn Sharp’s 1926 memoir)

Evelyn Sharp (1869-1955), the suffragist who became Hertha Ayrton’s official biographer, posed an interesting question for the Royal Society Secretary at this point. In June 1923 and amid other questions on Ayrton’s career, she asked ‘Should I be right in supposing that if Mrs Ayrton had lived, she would have the honour of being the first woman member of the Society?’

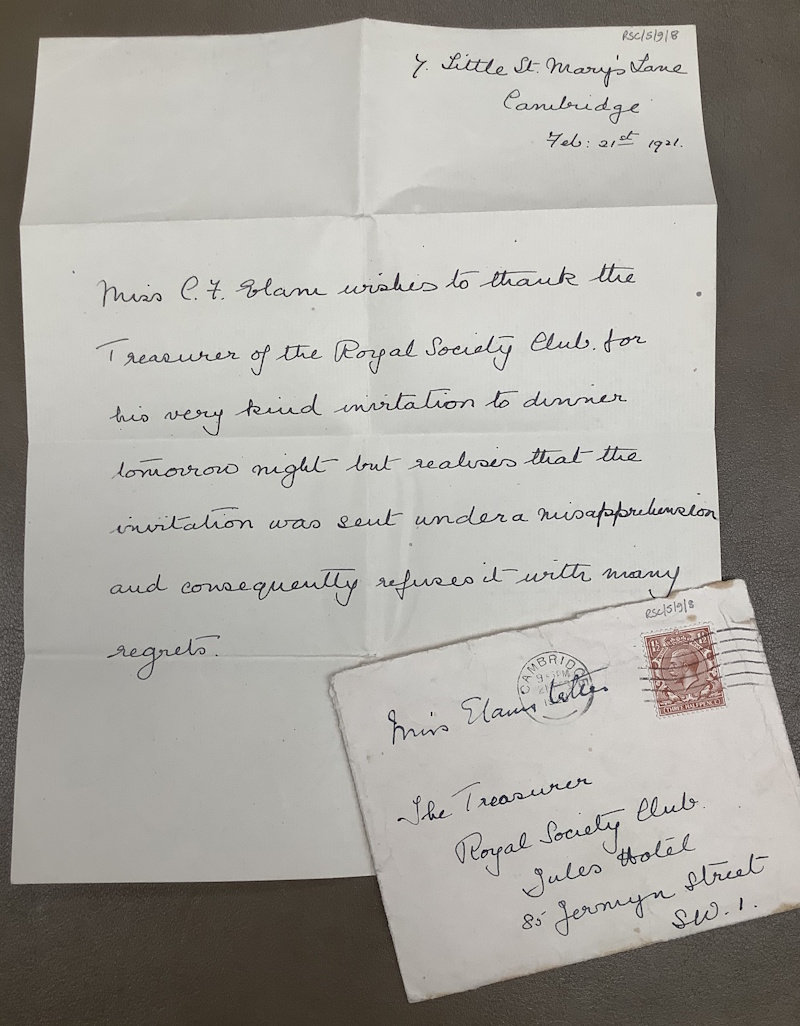

Two other incidents in the inter-war years are alternatively amusing and thought-provoking. The first involves the Royal Society Club, the dining group founded by Fellows as the ‘Thursday Club’ in 1743, for conviviality on the days when the Society met to discuss science. It was a tradition to invite Bakerian Lecturers to the Club, and in 1923, the podium was shared by G I Taylor and C F Elam, speaking on ‘The distortion of an aluminium crystal during a tensile test’.

The trouble (for the Club) was that no-one had realised that one author wasn’t Charles, Christopher or Colin, but rather Constance Fligg Elam. Before the poor Fellows could react to their heinous error, Miss Elam sent a gracious note, thanking the Club Treasurer, but ‘realises that the invitation was sent under a misapprehension’. The relieved Fellows followed things up with the inevitable ‘beautiful box of chocolates’. Constance Tipper (1894-1995) as she became, was a leading metallurgist, best known for her work from 1943 on brittle fracture in the rapidly built (and occasionally quickly sinking) wartime Liberty ships.

Letter from Constance Fligg Elam to Sir Henry Capel Loftt Holden FRS, Treasurer of the Royal Society Club, 21 February 1923 (RSC/5/9/8)

Letter from Constance Fligg Elam to Sir Henry Capel Loftt Holden FRS, Treasurer of the Royal Society Club, 21 February 1923 (RSC/5/9/8)

The second historical footnote is, like Evelyn Sharp’s question, another ‘what-if’. In July 1938, the naturalist John Stanley Gardiner FRS (1872-1946) wrote to the Society’s President, Sir William Bragg (1862-1942) asking about the Society’s position on electing women and suggesting that Sidnie Manton might be a candidate. Gardiner certainly knew what he was talking about: his own work on the Royal Society’s expedition to Funafuti in 1896, and elsewhere, was a forerunner of the Great Barrier Reef expedition of 1928, which he helped to plan. He also managed to get Sidnie Milana Manton (1902-1979) a Cambridge job as a demonstrator, then a role as one of the Australian expedition’s collectors and authors. This launched her distinguished career as an invertebrate zoologist. Sidnie Manton would be elected to the Royal Society in 1948, one of the earliest women to receive that honour.

Portrait of Sidnie Manton ©Godfrey Argent Studio (RS.14150)

Portrait of Sidnie Manton ©Godfrey Argent Studio (RS.14150)

Fascinating to imagine that if Gardiner had his way, we would be celebrating Sidnie Manton as the first woman Fellow, rather than Stephenson and Lonsdale. I thought it sad that Gardiner did not live to see Manton receive her very well-deserved Fellowship, but that was before looking at Sidnie Manton’s certificate of candidature. There, Gardiner’s name appears on the list of supporters. Rather touching, I think.