It seems like a lifetime ago that the Daffodil DNA Project started. Way back in 2019, Beaulieu Convent School was successful in receiving a Royal Society Partnership Grant to study the DNA sequences in daffodils.

In 2018, I was becoming a reasonably experienced 'head of biology' and looking at how to tackle some of the more challenging parts of the course. The abstract ideas of DNA sequencing and the accompanying computational techniques stood out as struggles, but then I started thinking about the way students approached biology. There was a strategy of seeking the path of least resistance, compartmentalising the topics and reducing processes to the minimum series of bullet points. It was a subject built upon recall, far from what biology means for me.

When I think of the great biologists, they share a trait; the ability to see commonality across different fields but revel in the details. There is an unsatiable curiosity, no final answers but always more to discover. I felt that this was missing in my students, they simply wanted to consume the knowledge without ever questioning “why?”.

But the Daffodil DNA Project changed all that. Students became contributors to science, invested in the journey rather than simply the destination. After the first year of the project, I could see the wider impact that the project was beginning to have on students, which naturally led to the desire to measure these changes. This is a project that I hope will continue indefinitely and so I am invested in the legacy beyond the usual timescales of a Partnership Grant.

One of the most conspicuous changes I noticed in the first year of the project was the aspirations of students. Typically students who chose A-level biology as a key subject, wanted to do something related to healthcare like medicine, midwifery or nursing. I saw some big changes, such as students who had wanted to do history now wanting to do biochemistry. So the question was whether this was only related to what they were seeing. Were their aspirations being limited by the lack of breadth that they came across? If this was the case, all we would have to do is share a presentation on every career and aspirations would change. Unfortunately, there seemed to be more to it than that, students needed to see how they fit into a particular career.

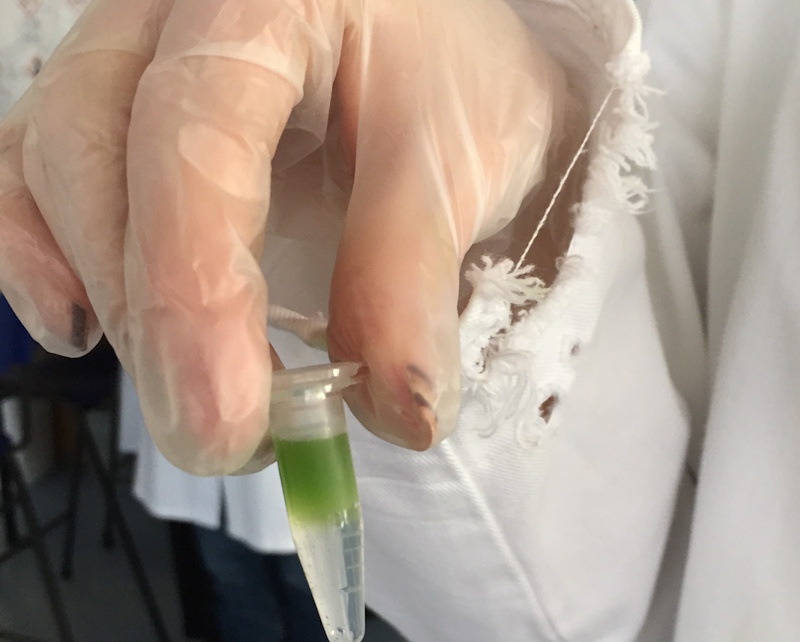

In year three of the project, this aspect became central. At each point in the method, students were having a meaningful interaction with scientists involved in that step, from recording observations from the field and preparing herbarium vouchers, to analysing the DNA sequences. Students were asking these scientists questions that went beyond the procedures and science, focusing on the more mundane aspects of the job, trying to gather information as to whether being a particular type of scientist was for them.

Coupling these interactions with the real research that the students were doing had a genuinely positive impact on the aspirations of these students. For three years in a row, all of the A level biologists have successfully gone on to study a biological subject at university, and they’ve also positively changed their attitudes towards mathematics and computing, which undoubtedly will become key for any biologist in the future.

As the project continued in my school beyond the initial Royal Society Partnership Grant funding, I became interested in formally collecting this data rather than simply relying on the anecdotal evidence I was witnessing. I used a couple of questionnaires to measure impacts and was delighted to share the results within a paper.

These results acted as a catalyst for the growth of the project beyond my own school, as the University of Dundee - and in particular Dr Liz Lakin - wanted to see if it could be scaled up and welcomed me into a part-time PhD programme to investigate the question.

It has been fantastic to see the project expand over the last few years to around 30 schools across the UK, with the support of the University of Dundee and the James Hutton Institute providing the majority of STEM partners for individual Partnership Grants. However, it is truly exciting to see scientists from other institutions and industry get involved in supporting young people to contribute to real science.

Daffodils are only one of our team’s specialities, so the vast majority of schools and STEM partners are truly collaborating and learning together. This project would not have been possible without the dedication of the teachers and students from all the schools involved. Similarly, each and every scientist has helped these young people and their teachers contribute to the body of scientific knowledge, from the James Hutton Institute, University of Dundee School of Life Sciences, Sellafield, University of Edinburgh, Royal Horticultural Society, University of Newcastle, University of Highlands and Islands, University College London, and Durrell Conservation.

A special thanks must go to James Abbott for his tireless dedication to make the data shine; Malcolm Macaulay and Craig Phillips for their support in running the teacher training activities; Jenna Foster for producing imagery to support the students’ understanding of the science and finally the Executive Group, chaired by Dr Liz Lakin, (University of Dundee, Education), supported by Drs Jorunn Bos, Davide Bulgarelli and Malcolm Macauley (STEM liaison), Dr Suzanne Duce (bioinformatics and digital resources), and Kevin Frediani (horticulture).