Guest blogger Louise Devoy reflects on the first generation of paid female astronomers at Greenwich, who helped to prove that women could actively contribute to professional science.

As we continue to mark the 80th anniversary of the election of the first female Fellows of the Royal Society, here’s a guest post from the Royal Observatory commemorating some earlier pioneering women in STEM:

In July 2025, Professor Michele Dougherty FRS was appointed as the sixteenth Astronomer Royal, the first female post-holder since the role began in 1675. It’s an exciting milestone moment that offers us a great opportunity to reflect on the first generation of paid female astronomers at Greenwich – the ‘Lady Computers’ of the 1890s – whose ingenuity, tenacity and perseverance proved that women could actively contribute to professional science.

Women have always played an important role in the life and work of the Observatory. With the Astronomer Royal expected to live onsite, it was natural for the women in his household to take an interest in the Observatory’s activities. For example, Margaret Flamsteed, wife of the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed FRS, took on the arduous task of assembling and publishing Flamsteed’s work after his death in 1719 to ensure that his catalogue of 3,000 accurate star positions would not be forgotten.

Over the centuries, successive generations of wives, daughters and sisters supported the Astronomer Royal by receiving guests, providing illustrations for books, and even accompanying their husbands on eclipse expeditions. As demonstrated by surviving letters in the RGO Archives and the Royal Society Archives, we can see how they were embedded within a network of astronomers’ wives who took a keen interest in the scientific debates of the day. In addition, census records reveal how Flamsteed House, the dwelling space of the Astronomer Royal and his family, was the workplace for a small team of domestic servants, both male and female.

Cleaner Mrs Dignum stands proudly with her vacuum cleaner in front of John Harrison’s first marine timekeeper, ‘H1’, as displayed in the Octagon Room in 1933. © National Maritime Museum, London (AST1113.43)

Cleaner Mrs Dignum stands proudly with her vacuum cleaner in front of John Harrison’s first marine timekeeper, ‘H1’, as displayed in the Octagon Room in 1933. © National Maritime Museum, London (AST1113.43)

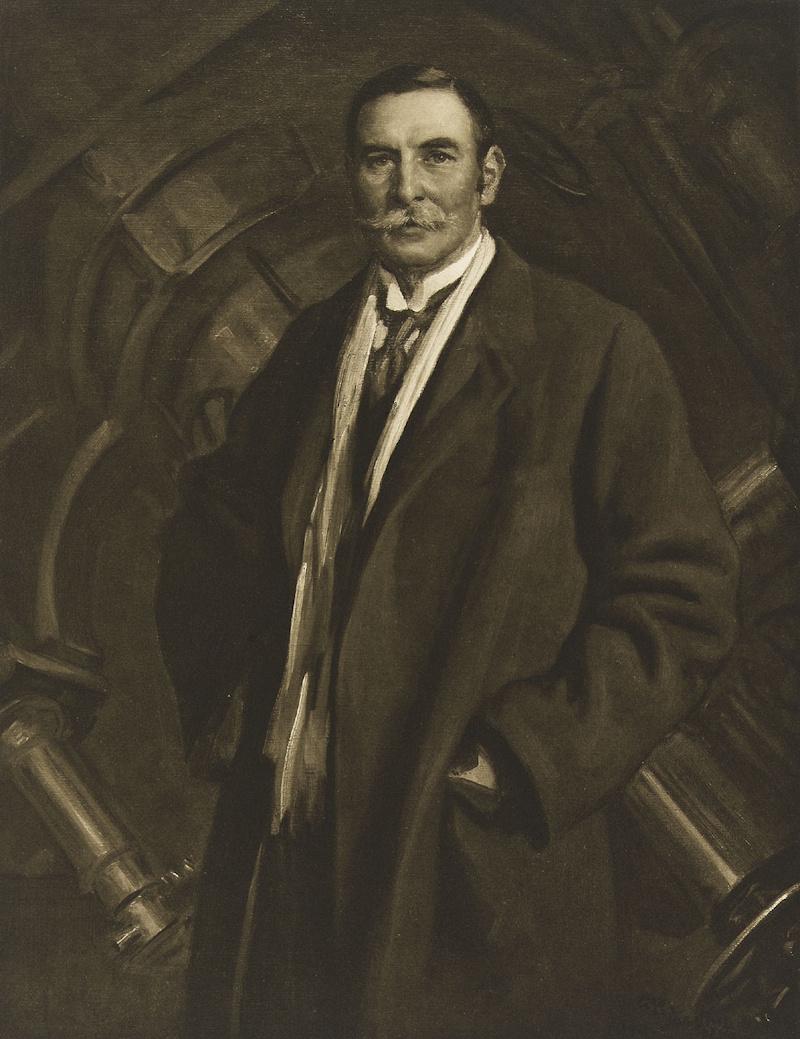

Working as a female professional astronomer at Greenwich was another matter entirely, one that did not take shape until the 1890s with the arrival of a new photographic project. In April 1887, the eighth Astronomer Royal, William Christie FRS, travelled to Paris Observatory where he and other observatory directors agreed to create a giant photographic atlas and catalogue of the night sky. Each observatory was assigned a specific part of the sky and the directors expected to finish the project within five years. It soon became apparent that the task was much more demanding and labour-intensive than previously imagined, leading some of the directors to recruit women – daughters, teachers and even nuns – as cheap labour.

William Christie © National Maritime Museum, London (PAH5622)

William Christie © National Maritime Museum, London (PAH5622)

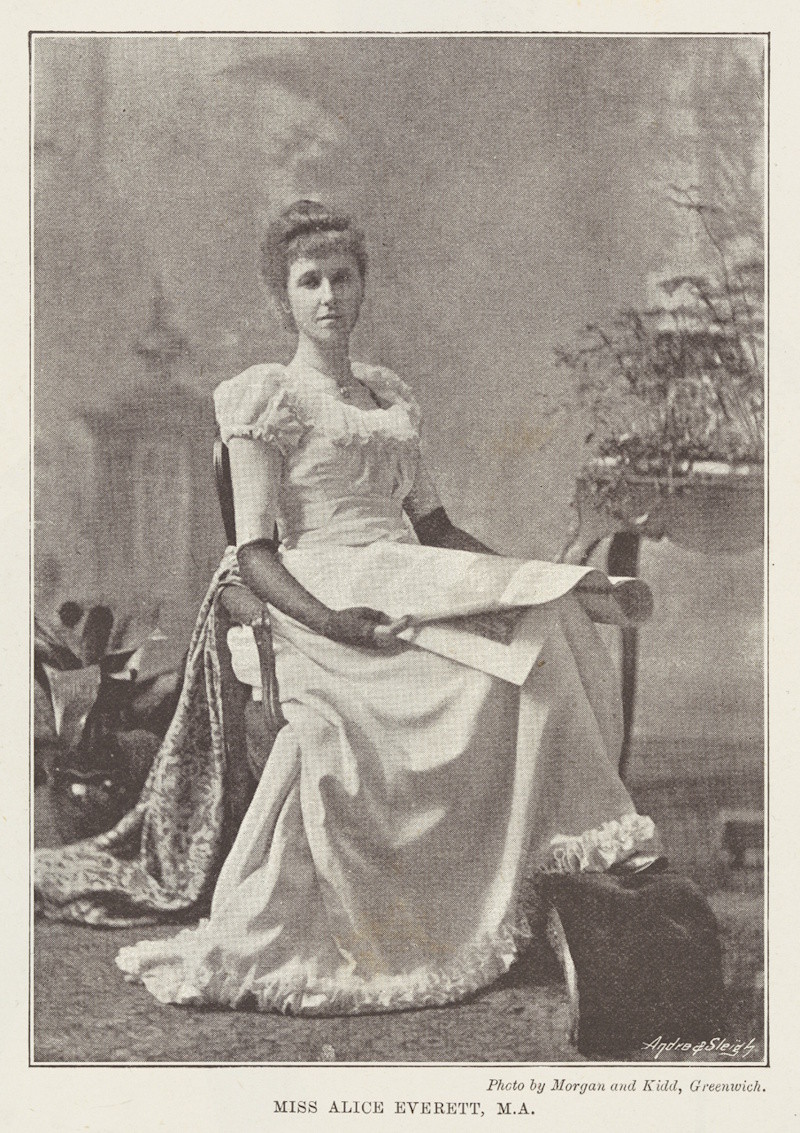

In the spring of 1890, Christie decided to recruit a small group of women mathematicians from the all-female colleges at Cambridge University – Girton and Newnham – to help with the Astrographic Department. Despite having completed the same courses and exams as their male counterparts, the women were denied receiving full degree certification, a situation that did not change until 1948! Once at Greenwich, the ‘Lady Computers’ were also paid the same lowly rate as the teenage boy ‘computers’, rather than the higher rate paid to their fellow male assistants. It was a disappointing offer for such educated women, but four candidates decided to take on the role: Isabella Clemes, Alice Everett, Harriet Furniss and Edith Rix. With the resignations of Clemes and Furniss in 1891, Christie filled the gap by recruiting Annie Scott Dill Russell, a Girton classmate of Alice Everett, who started in September 1891.

Alice Everett © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

Alice Everett © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

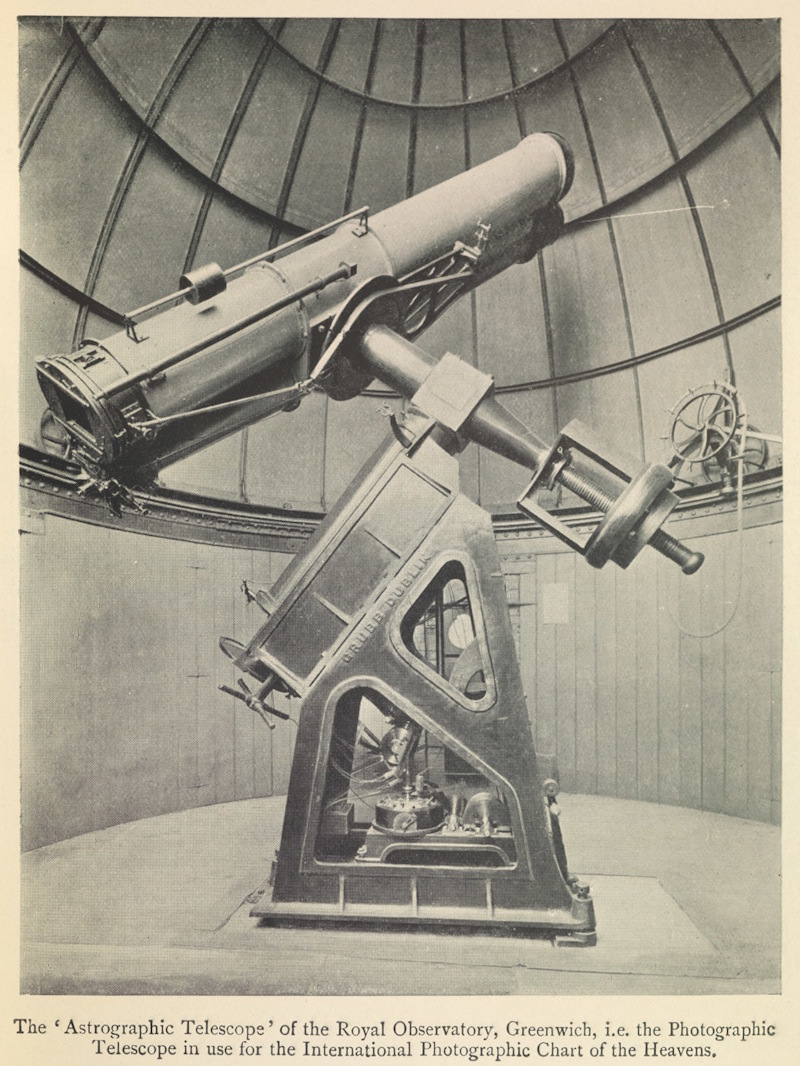

In November 1893, Everett was the subject of an interview in The Sketch that gives us an insight into the Lady Computers’ weekly routine, which involved a combination of two evenings of photographic observations and a mixture of morning and afternoon sessions in the office for computations. Working in pairs, the women used the bespoke Astrographic Telescope to systematically photograph the sky, capturing a mixture of long (40 minutes) and short (a few minutes) exposures. Everett and Russell also learned how to operate the Sheepshanks Equatorial Telescope, which they used to make observations of comets and Mars.

The 13-inch diameter Astrographic Telescope at Greenwich © National Maritime Museum, London

The 13-inch diameter Astrographic Telescope at Greenwich © National Maritime Museum, London

After a flurry of press interest at the time of their recruitment, the work of the Lady Computers seemingly disappears from view. Our next clue appears in 1904 with Christie’s publication of the Observatory’s first volume for the International Astrographic Catalogue, an achievement that few other observatories accomplished. If we look closely, we can find Everett mentioned as one of the plate measurers from October 1894, but there’s no reference to the earlier observations of the other Lady Computers.

This omission is indicative of the wider struggles that the women faced in seeking recognition for their work. Prohibited from joining professional organisations such as the Royal Society and the Royal Astronomical Society, the Lady Computers could only join the British Astronomical Association, which was open to anyone interested in astronomy, regardless of gender or professional status. For Everett and Russell, the BAA became a valuable forum for establishing their identities within the astronomical community.

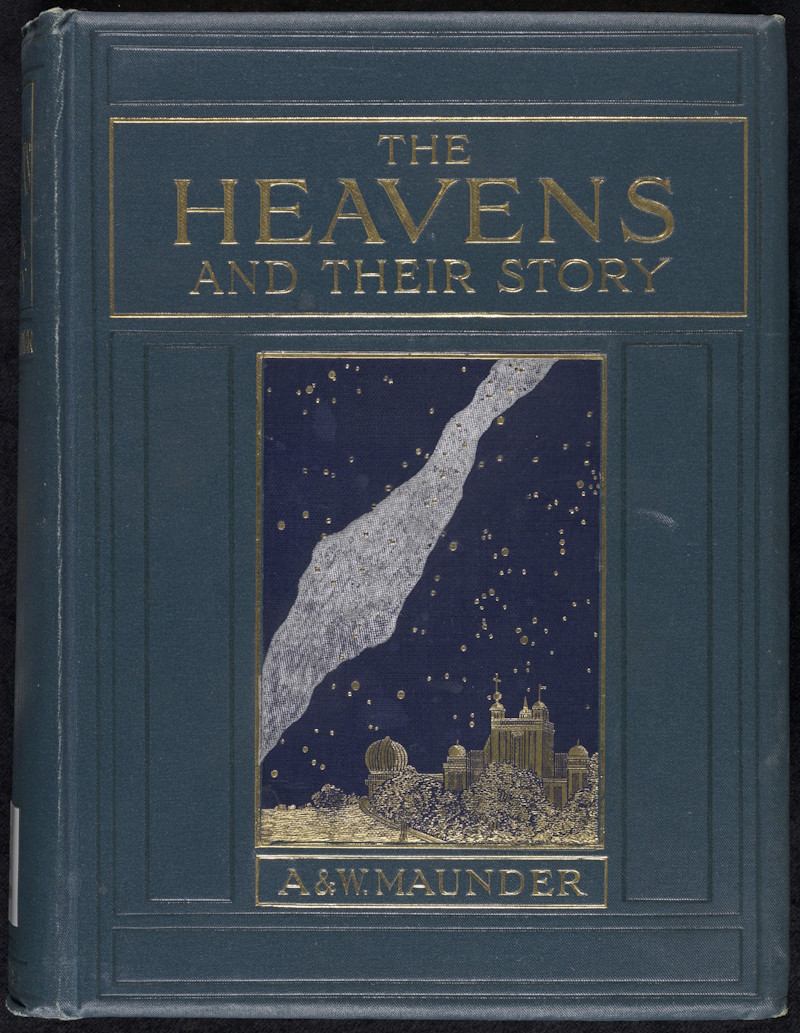

By October 1895, all the Lady Computers had left the Observatory. Everett continued working on the International Astrographic Project for another three years at Potsdam Observatory, but struggled to sustain a career in astronomy and later developed her interests in optics at the National Physical Laboratory. Russell married her colleague E Walter Maunder in December 1895 and became renowned for her pioneering solar eclipse photography and popular astronomy books. We continue to celebrate her achievements at Greenwich today with our Annie Maunder Astrographic Telescope and the Annie Maunder Open Category as part of our Astronomy Photographer of the Year competition.

The Heavens and their story, by A & W Maunder, 1908 © National Maritime Museum, London

The Heavens and their story, by A & W Maunder, 1908 © National Maritime Museum, London

Find out more…

Bigg, Charlotte, ‘Photography and labour history of astrometry: The Carte du Ciel’, Acta Historica Astronomiae, 9: 90–106 (2000)

Brück, M. T., ‘Alice Everett and Annie Russell Maunder: torch bearing women astronomers’, Irish Astronomical Journal, 21(3/4): 281-291 (1994)

Brück, M. T., ‘Lady Computers at Greenwich in the early 1890s’, Quarterly Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society, 36: 83-95 (1995)

Devoy, Louise, Royal Observatory Greenwich: A History in Objects, National Maritime Museum (available from October 2025)

Dolan, Graham, ‘Christie’s ‘Lady Computers’ – the astrographic pioneers of Greenwich’

Kidwell, Peggy, ‘Women astronomers in Britain, 1780-1930’, Isis, 75(3): 534-546 (1984)

Ogilvie, M. B., ‘Obligatory amateurs: Annie Maunder (1868–1947) and British women astronomers at the dawn of professional astronomy,’ British Journal for the History of Science, 33(1): 67-84 (2000)