Intrigued by a portrait that was briefly part of the Royal Society’s collection, Ainsley Vinall investigates some other 'paintings that got away'.

Ahead of our Scientific Portraits and Portraits for Science conference, to be held at the Royal Society in March 2026, I’ve been looking into the provenance of some of the paintings in our collection.

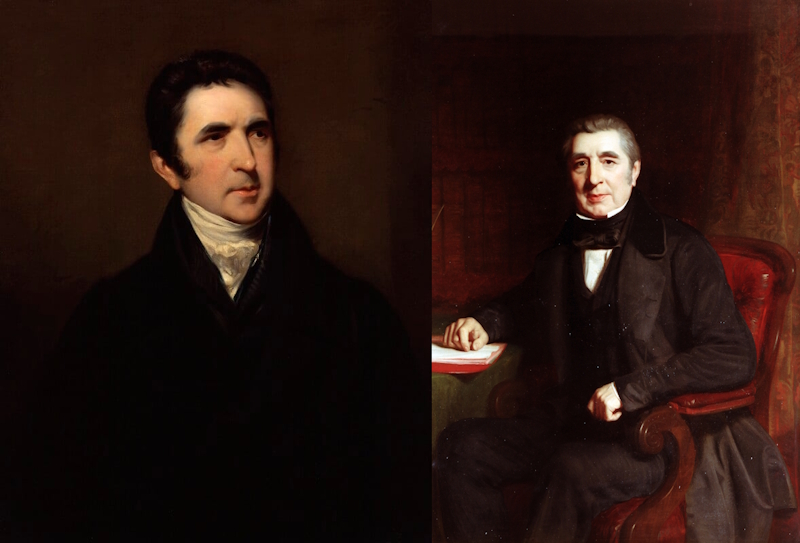

While checking the acquisition date of our portrait of John Barrow FRS (1764-1848), I noticed that it had come to us via a rather unusual route: rather than being purchased or received as a gift, it was acquired in exchange for a different portrait of Barrow we already held! This has led to some confusion over the identity of the artist, as our early catalogues didn’t distinguish between the two paintings.

The first one we received, a copy after a painting by John Jackson now in the National Portrait Gallery, was presented by John Barrow himself in 1846. However, in 1865 we received a letter from the painter Stephen Pearce explaining that he had, some years earlier, painted a portrait of Barrow from life and that Barrow’s family would now like to present this painting to the Royal Society in exchange for the earlier Jackson copy. Council agreed with the proposal and by January 1866 the swap had taken place.

(L) John Barrow, attributed to John Jackson, c.1810 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 886). (R) John Barrow, by Stephen Pearce (1819-1904), c.1840s (RS.9641)

(L) John Barrow, attributed to John Jackson, c.1810 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 886). (R) John Barrow, by Stephen Pearce (1819-1904), c.1840s (RS.9641)

The family then seems to have kept the Jackson copy for a few generations, as it is likely this is the painting that was later presented to the Africana Museum in Johannesburg (now known as Museum Africa) by Barrow’s great-great-grandson Wilfred Barrow, as noted in the extended catalogue entry for the NPG portrait. Intrigued by this painting that was briefly a part of the Royal Society’s collection, I began to research some others that slipped through our fingers.

For a while in 1869 we held another painting by John Jackson, showing Royal Society President Humphry Davy FRS (1778-1829). This occurred shortly after the death of chemist John Davy FRS (1790-1868), who left the Royal Society his own painted portrait as well as a set of silver plates from his more famous brother. The plates were left with instructions that they should be melted down and sold to fund an annual award for outstanding work in chemistry, the Davy Medal, still awarded by the Royal Society every year.

Although we held a large painting of Humphry Davy, presented by his widow Jane in 1829, the Society wanted the portrait on the Davy Medal to be based on a simpler likeness, and therefore borrowed a small John Jackson painting from the Davy family. Whilst the medal was being designed and cast, the Fellows were also deliberating over the John Davy portrait: they did want to acquire the picture, but it was only offered on condition that it would ‘be allowed a place in the meeting room near my brother’. Ultimately the Society accepted the painting on these conditions, but then agreed to loan it back to John’s daughter, Grace Rolleston, for the remainder of her life.

After Grace’s death in 1914, her son Humphry Rolleston dutifully got back in touch with the Royal Society to return the portrait, only to be told that Council had determined that ‘lack of wall space in the Meeting Room now makes it impossible for them to observe the conditions of the bequest’. The donation was therefore declined after all. Not many details are given about the portrait, but it has been conjectured that the artist could be Spiridione Gambardella, so it’s likely that this is the portrait of John by an Italian painter reproduced in Anne Treneer’s 1963 biography The mercurial chemist: a life of Sir Humphry Davy:

John Davy, by an unknown Italian artist, c.1825 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

John Davy, by an unknown Italian artist, c.1825 (public domain via Wikimedia Commons)

Although somewhat overshadowed by his more flamboyant brother, John Davy was a noted chemist and physician who discovered a number of chemical compounds. As the Royal Society declined to receive his painting, no likeness of him is currently on display in any public institution.

As for the Jackson portrait of Humphry Davy, this was returned to the family once the medal had been produced. However, word must have spread, as we were offered another Humphry Davy portrait in 1897. The suggestion came from Victoria Mary Louise King, whose late husband had been the nephew of Davy’s close friend Thomas Poole. Davy had left Poole some money to ‘purchase some token of remembrance’, which he had used to buy a portrait of a young Davy painted in 1803 by Henry Howard. Victoria now intended to sell this painting and offered it to the Royal Society first.

The matter was referred to the Treasurer, John Evans FRS (1823-1908), who declined the offer, likely as the Society already owned the larger portrait of Davy. The Howard painting is now at the National Portrait Gallery, having been purchased at auction in 1967; it is held alongside the smaller John Jackson portrait, presented by the Davy family in 1917:

(L) Humphry Davy, by Henry Howard, 1803 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 4591). (R) Humphry Davy, by John Jackson, c.1820 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 1794).

(L) Humphry Davy, by Henry Howard, 1803 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 4591). (R) Humphry Davy, by John Jackson, c.1820 © National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG 1794).

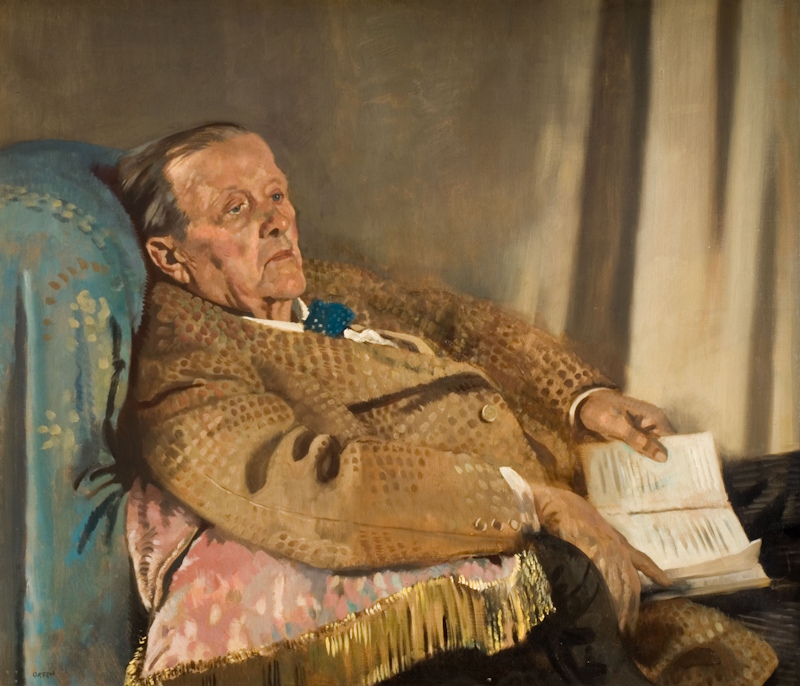

Lack of wall space and a stricter acquisition policy seem to have slowed down our portrait collecting in the twentieth century. When the Officers were notified that a portrait of the prominent evolutionary biologist Ray Lankester FRS (1847-1929) was up for sale in 1942, they declined to purchase it, noting that to do so ‘would be at the risk of creating a new and awkward precedent if we thus used the Society’s funds to purchase a portrait of a recent Fellow, however eminent, whose association with the Society never reached the stage of holding office.’ The painting was instead purchased for Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery:

Edwin Ray Lankester, by William Orpen, 1928 (public domain via Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery)

Edwin Ray Lankester, by William Orpen, 1928 (public domain via Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery)

Over the years, shifting attitudes and varied collecting policies have shaped the portrait collection at the Royal Society. The collection includes a number of understudied anomalies, including portraits of non-Fellows and paintings with unknown acquisition dates. If you’re interested in learning more about scientific portrait collections and how scientists have made use of portraits, keep an eye out for our upcoming Scientific Portraits and Portraits for Science conference next March – we’re aiming to launch the registration page early in the new year.