Royal Institution: science education

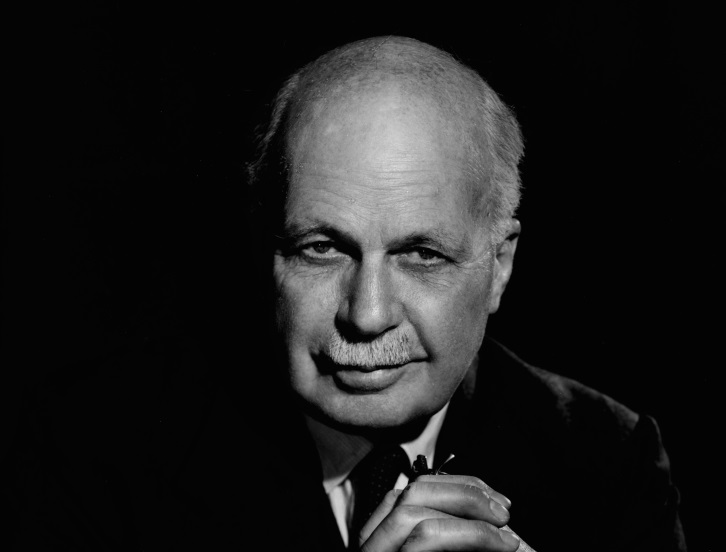

Sir William Lawrence Bragg ©Godfrey Argent Studio

Sir William Lawrence Bragg (1890-1971) was for many years the youngest ever Nobel Prize-winner for science – the award (for Physics) came in 1915. Bragg’s work in crystallography, and particularly in X-ray diffraction, opened up new techniques for analysing molecular structures and resulted in some of the most important science of the 20th century.

Small wonder that the very eminent scientist of the late 1950s, by now Fullerian Professor of Chemistry at the Royal Institution of Great Britain, should be interested in educational work with the young as part of the tradition of engagement with general audiences for which the Royal Institution has long been famous. Lawrence Bragg’s approach to the Wolfson Foundation, in March 1959, was to support just these activities – in aiding teaching within London schools, but also by investigating the best ways to approach young minds and their teachers with scientific ideas.

The Wolfson Foundation topped up the Royal Institution’s ongoing costs by the relatively small sum of £2,000, citing the work in other English cities being done by the Institution. But as can often happen, small grants may lead to bigger ones. Wolfson Foundation staff, visiting the Royal Institution’s Open Day exhibition of developments in X-ray crystallography, noted how X-ray techniques linked two existing Wolfson grants: the Chair in Metallurgy at Oxford, and Dorothy Hodgkin’s Wolfson Professorship from the Royal Society, each concentrating on crystallographic studies of this type. The way appeared to be open for another Fellowship, based at the Royal Institution “outside the range already supported by the Medical Research Council, and only if the right man was available”; at which point the file closes, with the idea intriguingly unresolved.

Explore the archives

- WF/23/1a, b

Pamphlet on the foundation, history and activities of the Royal Institution of Great Britain, late 1950s [cover and p.1 only] - WF/23/2, b

Article, ‘ “Schools Lectures” at the Royal Institution’, by Sir Lawrence Bragg, Discovery, January 1957 - WF/23/4, b, c

‘Approach to the Wolfson Foundation’, 23 March 1959, by The Royal Institution - WF/23/5

Letter from Sir William Lawrence Bragg, 23 March 1959, to Arthur Lehman Goodhart, University College, Oxford - WF/23/6

Memorandum from Sir Harold Redman, 7 April 1959, to Wolfson Trustees - WF/23/8

Letter from Sir William Lawrence Bragg, The Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, 7 April 1959, to Sir Harold Redman, The Wolfson Foundation - WF/23/9, b

Letter from Sir Harold Spencer Jones and Sir William Lawrence Bragg, The Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London, 9 April 1959, to Sir Harold Redman, The Wolfson Foundation - WF/23/12

Letter from Sir Harold Redman, The Wolfson Foundation, 22 June 1959, to Sir William Lawrence Bragg, The Royal Institution, 21 Albemarle Street, London - WF/23/19

Royal Institution Open Day announcement, ‘The Development of X-ray analysis’, June 1962 - WF/23/22, b

Memorandum on a visit to the Royal Institution’s Open Day by Sir Harold Redman, 14 June 1962