Alan Turing and DNA papers among historical peer review reports made public for first time

25 September 2024The Royal Society has today released over 1,600 historical peer review reports, available to view publicly for the first time on the Science in the Making portal.

Readers can discover what eminent scientists thought of work by mathematician Alan Turing, as well as Nobel Prize-winning chemist, Dorothy Hodgkin’s review of Crick and Watson's famous “DNA” paper.

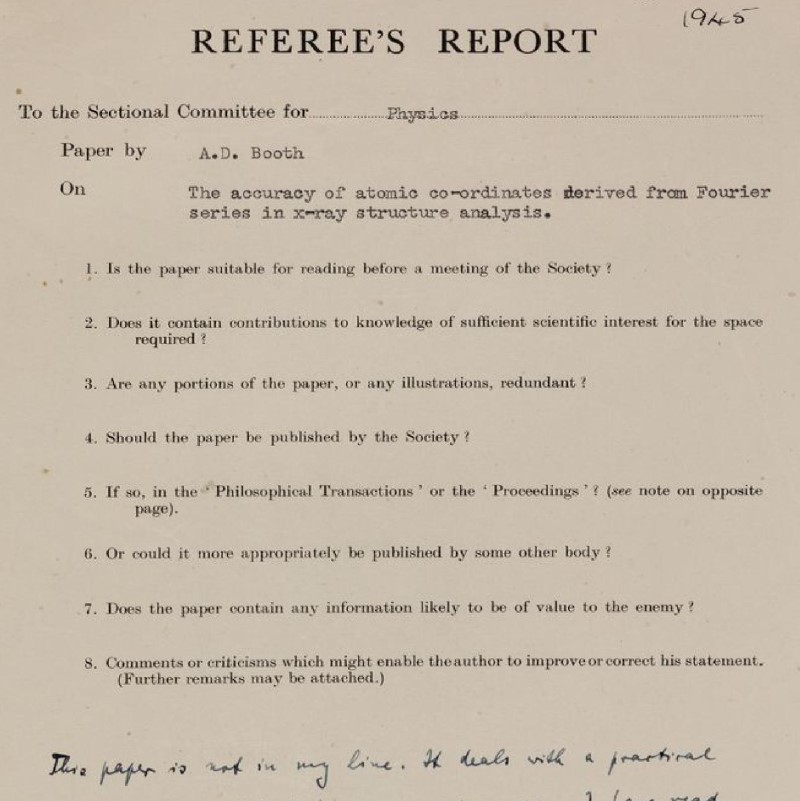

The reports, dating from 1949 and 1954, have until now been closed to researchers following a 70-year moratorium in respect of confidentiality and privacy laws. They have been added to a unique archive of referee reports dating back to 1831, allowing researchers to retrace the history of scientific peer-reviewing.

The Royal Society’s historian, Louisiane Ferlier, said: “Peer review is a vital part of all scientific endeavour. It is of course a crucial process of verification but also a unique meeting (or clashing) of minds. It’s exciting that readers can finally glimpse behind the scenes at the fascinating critiques and praises for some of the most groundbreaking papers and theories of the time, from the structure of DNA to the physiology of mushrooms.

“These newly released papers also demonstrate the arrival of more women in the Royal Society referee process in the late 1940s and 50s. Readers can delve into reports by some of our first female Fellows, Dorothy Hodgkin and Kathleen Lonsdale, who reviewed various papers by other prominent scientists. It is a wonderful way to better understand the influential role women played in the history of scientific publication.”

As one of the first women involved in the peer review process of a Royal Society journal, Dorothy Hodgkin featured as the sole referee of one of the most important papers for modern science: ‘The complementary structure of deoxyribonucleic acid’, better known as “DNA” by Francis Crick and James Watson. The paper was presented at the Royal Society's Summer Soirée the same year by biophysicist, Rosalind Franklin, whose work was critical to resolving the structure of DNA.

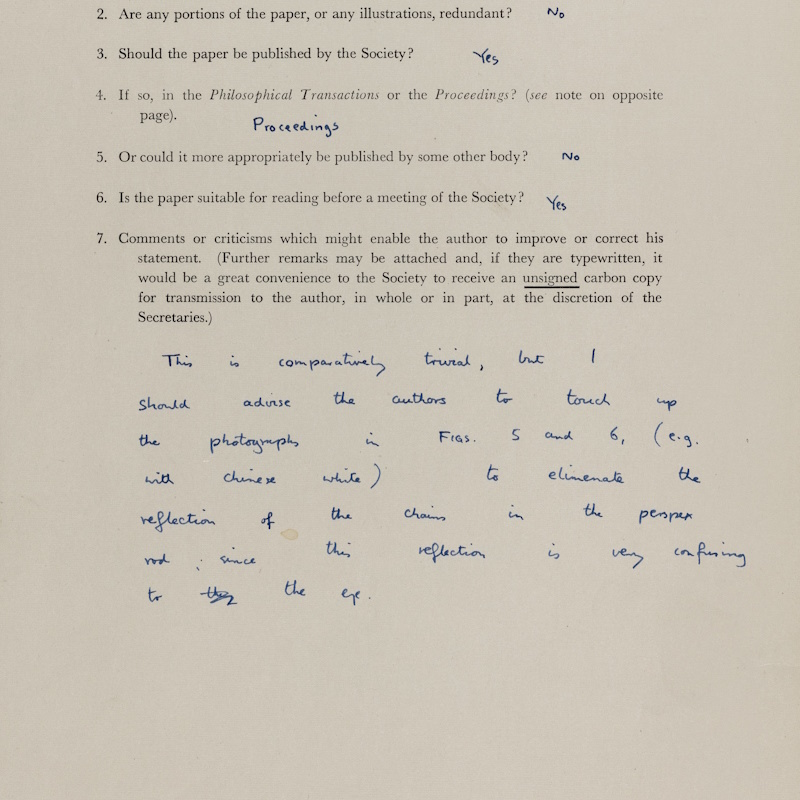

Hodgkin’s one suggestion reads:

“This is completely trivial, but I should advise the authors to touch up the photographs in figs. 5 and 6, (ep with Chinese white) to eliminate the reflection of the chairs in the perspex rod: since this reflection is very confusing to the eye.”

In the final paper, the rod instead appears as a clear white line, resolving Hodgkin’s comment.

Readers can also find Hodgkin’s referee report of Rosalind Franklin’s paper on ‘Crystallite growth in graphitising and non-graphitising carbons’, where she notes how she feels “incompetent” to review the paper, not being an expert in the field.

Alan Turing’s paper on “the chemical basis of morphogenesis” proposes new methods of mathematical modelling for the biological field, including the use of computers. A negative review by scientist J.B.S Haldane states: “I consider that the whole non-mathematical part should be re-written." Physicist and grandson of Charles Darwin, Charles Galton Darwin says: “his paper is well worth printing, because it will convey to the biologist the possibilities of mathematical morphology more definitely than has often been done hitherto.”

Ferlier said: “This is a fascinating example of how the peer review process can bring together scientists across fields. What is even more interesting, however, is that the final published article seems to have taken little notice of the criticisms, leaving Darwin and Haldane’s comments unaddressed.”