Keith Moore pays a visit to Dorset, and discovers the links between fossil collector Mary Anning and Royal Society Fellows William Conybeare and Henry de la Beche.

The coastline around Lyme Regis was bathed in half-term autumn sunshine for most of last week and its cliffs were ringing with the hammers of pint-sized chain gangs breaking rocks for ammonites. Two hundred years ago there were few fossil-hunters but their quest for unknown saurians produced a sensational period of discovery.

David Attenborough and Tracey Chevalier were among those launching a programme of festivities at the Philpot Museum to mark the opening of the Royal Society-sponsored Local Heroes exhibit Mary Anning and the Men of Science, which runs until spring 2011. Anning was of course the local woman who linked Dorset with the more formal nineteenth-century geological community, racking up many discoveries including finding the first British pterosaur.

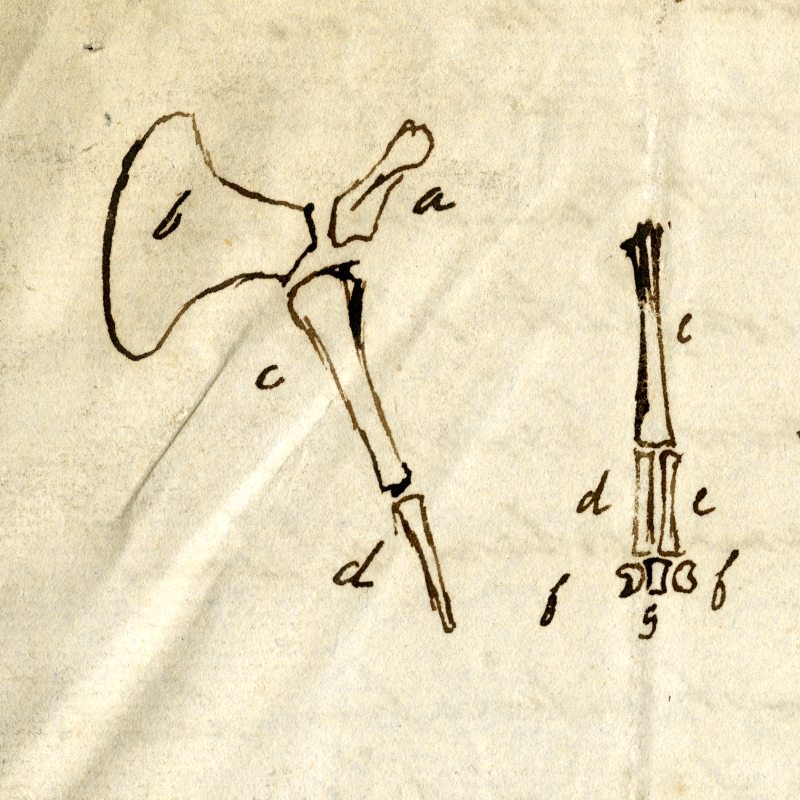

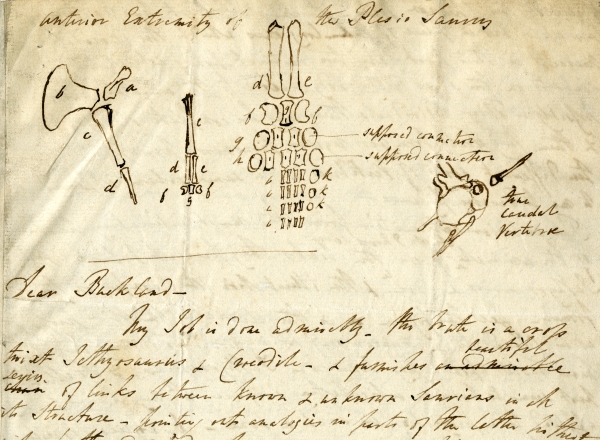

Selling fourteen-foot skeletons was a precarious way to make a living, but Anning established a ready market for specimens. One of the most significant is recorded in a small letterhead sketch in the Royal Society’s archives in which William Daniel Conybeare (1787-1857) described the paddles of a sea creature to the Oxford geologist William Buckland. It was the most famous of marine reptiles, dubbed 'Plesio-Saurus' by Conybeare. Eager to get into print (mostly to pre-empt Sir Everard Home, who had written widely, if erroneously, on the same topic) Conybeare didn’t credit Anning’s assistance: 'I expect by speedy publication to secure this discovery to myself & Mr de La Beche who meticulously helped me especially in drawing”, he wrote. The completed paper was Notice of the discovery of a new fossil animal forming a link between the Ichthyosaur and Crocodile… (1821) and Everard Home was comprehensively 'kicked down the stairs'. Not that Conybeare was gloating. By 1823 Anning had found a complete plesiosaurus, confirming many of Conybeare’s ideas.

Plesiosaur fossil by William Conybeare FRS, 1821 (MS/251/20)

Co-author Henry de la Beche (1796-1855) was a longstanding friend of Anning’s and he made amends by producing the extraordinary watercolour Duria antiquior (1830) to support her financially. This landscape was a bold visualisation of ancient Dorset life based upon Anning’s animal and plant fossils. The work is engrossing in its detail, scientifically defensible even to climatic and behavioural elements and daring in its omissions – there is no human presence here.

To find out what motivated Anning and her peers I had to try finding fossils for myself. It is curiously exciting to see something so old revealed by splitting a tide-rolled stone. My own moment came on Monmouth Beach in Chippel Bay as a small serrated edge and black point stood out from my cracked rock. Scalpel-work revealed a beautifully reticulated shark’s tooth, baroquely detailed, with nearby, a fossilized fish-scale. I half-hoped the tooth would belong to the local beast Hybodus delabechei (after Henry) but later the more expert eyes of Chris Andrew at the Fossil Workshop gave it the preliminary identifications of Hybodus cf. reticulates or perhaps Palidiplospinax sp. I handle archival objects routinely, all of them made to be read and seen: quite different to being the first to view something discarded on the ancient sea-bed those millions of years ago.