Read more about the story of Hertha Ayrton and the Royal Society.

Early in January 1902, the Secretary of the Royal Society received a short but startling communication from John Perry FRS. On a single sheet of notepaper was written the following:

To the Secretary, the Royal Society

Gentlemen

I enclose a form of application for membership on behalf of Mrs Hertha Ayrton, duly signed

I am gentlemen

Your obedient servant

John Perry

Perry was an electrical engineer, and had been Professor of Engineering and Mathematics at Finsbury Technical College. He had collaborated for many years with Will Ayrton FRS, another electrical engineer at the Technical College, and it was on behalf of Will’s wife Hertha that the nomination had been prepared.

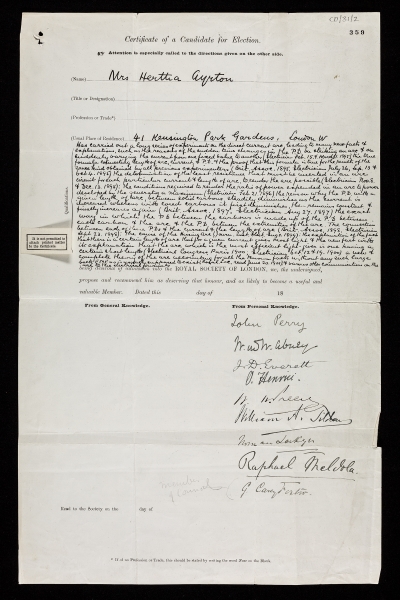

Hertha Ayrton's nomination certificate

Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923) was born Phoebe Sarah Marks but was named Hertha by a friend while a teenager, after Swinburne’s poem about the earth-goddess Erda. The name stuck, perhaps because of Hertha’s innate vitality. Later in life one of her friends said of her ‘If she paints shelves, she paints them as if nothing in the world mattered except painting shelves!’ Introduced to the study of mathematics by her cousin, Hertha began her working life as a governess at the age of sixteen to provide for her invalid mother. Later she met Barbara Bodichon, the founder of Girton College (Cambridge’s first college for women), and won a scholarship to continue her studies at Girton. She studied mathematics and physics, and founded the Girton Fire Brigade. She was a friend of George Eliot, who may have based the character Mirah in Daniel Deronda to some extent on Hertha.

On her return to London, Hertha attended evening classes at Finsbury Technical College taught by Will Ayrton. They married in 1885, and both worked on electricity. The results of Hertha’s experiments with the electric arc were published in twelve papers in The Electrician (1895-6), and she made a demonstration at the Royal Society’s Conversazione (an exhibition of scientific work) in 1899. She spoke on ‘The hissing of the electric arc’ at the Institution of Electrical Engineers, who elected her a member (the only woman to be elected until 1958). John Perry gave her paper on ‘The mechanism of the electric arc’ at the Royal Society in 1901, and in 1902 she published 'The Electric Arc', which became the standard work on the field. She later patented anti-aircraft searchlights, developed for the Admiralty, and arc lamp technology.

With all this work to her name, and with the support of nine Fellows who signed her certificate of candidacy ‘from personal knowledge’, what became of Hertha’s nomination to the Royal Society? It was taken to Council as a first step. Not wanting to act hastily (or rashly), the Council sent off for a legal opinion on the case. The papers are preserved in the Society’s archive and make interesting, though rather depressing, reading. Here is an extract from the Royal Society Council’s statement of the case:

“For the first time it is believed in the history of the Society a Certificate in all other respects perfectly regular has been delivered to the Assistant Secretary contining the name of a female candidate for the Fellowship, the lady being the Wife of a Fellow of the Society. The Secretaries have brought this Certificate to the notice of the Council asking for directions and the Council have decided that before coming to any conclusion as to whether the Certificate shall be registered and read at an ordinary meeting as required by the Statutes the opinion of Counsel shall be taken as to the duty and powers of the council in the matter.

From the complete list of Fellows . . . it is clear that no lady ever has been elected a Fellow of the Society and though a bust of the distinguished Mary Somerville stands in a place of honour in the Library of the Society . . . the archives of the Society so far as can be ascertained contain no evidence that either she or any other woman was ever even nominated for the Fellowship. The Statutes of the Society from its incorporation . . . and indeed the rules of the Society of 1660 before its incorporation, always refer to Fellows and Candidates for the Fellowhips as “he” or “him” the rules of 1660 stating “that no man shall be elected the same day he is proposed”.

On the other hand the Charters do not appear to contain any words which would not refer to women equally with men. The Fellows are termed “sodales” which does not seem to be confined in meaning to men . . . ”

I find it rather curious that Mary Somerville’s bust is introduced into this document, as though having a marble statue of a lady ‘in a place of honour’ in the Library might somehow create a precedent for having a flesh-and-blood lady among the Fellows. The legal counsel W. O. Danckwerts KC seems not to have taken any notice of this irrelevancy, but in his response cuts straight to the chase:

“We are of opinion that married women are not eligible as Fellows of the Royal Society. Whether the Charters admit of the election of unmarried women appears to us to be very doubtful. Certainly the statutes of the Society are framed on the footing that only men can be elected, and we think that no woman can be properly elected as a fellow even if the Charters admit of such election without some alteration in the statutes. A woman if elected would become disqualified by marriage. Under all the circumstances we think that if the Society desire that women should be eligible as fellows it would be wise to apply for a supplemental Charter rather than to proceed by way of passing a new Statute the validity of which if passed to admit unmarried women, might having regard to the doubtful construction of the existing Charters remain a matter of uncertainty.

Married women could not be made eligible by Statutes”

The situation, in a nutshell, was that in common law, married women had no status – they were not regarded as ‘persons’ in the eyes of the law. As such, they could not be fellows of a society incorporated by charter. In the event the Society did not apply for a supplemental Charter, but instead ordered the Secretary to convey the judge’s opinion to John Perry. And not only John Perry – the legal papers were ordered to be printed and sent to all the Fellows (presumably in a bid to avoid receiving further nominations of women). This gambit worked so well that the next time women were considered for the Fellowship occurred in 1945, despite the Council’s explicit statement in 1922 that the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act of 1919 meant that women could no longer be barred by existing statues or charters.

And what of Hertha Ayrton? She went on to report her work on wavelengths, eddies and vortices in person at the Society several times, and in 1906 she won the Society’s Hughes medal for her work on the electric arc and on sand ripples. (It was another 102 years before the Hughes medal was again awarded to a woman.) Hertha was also an active suffragette, taking part in processions and protests, at considerable personal risk. In 1910 she wrote in a letter to the Times:

‘I was marching immediately behind Mrs Pankhurst when she entered Downing Street, but was prevented from reaching No. 10 by an attempt at strangulation on the part of a policeman. . .’. In 1912 her daughter Barbara was taken to prison following a demonstration: Hertha sent news of this to her stepdaughter with the words ‘Barbie is in Holloway . . . I am very proud of her’.

History is silent about Hertha’s response to the failed Royal Society nomination, but she and her friends in the women’s movement must have known that the time was coming when they could no longer be denied education, voting rights, or even membership of learned societies on the grounds of sex.

Happy International Women’s Day!

[You can read more about Hertha Ayrton in Joan Mason’s Notes and Records article ‘Hertha Ayrton (1854-1923) and the Admission of Women to the Royal Society of London’.]

Portrait photograph from "Hertha Ayrton: a Memoir" by Evelyn Sharp (London, Edward Arnold & Co,1926)