Read more about a pear-shaped and lurid tale Rupert Baker found while digitising images for the Royal Society's picture library.

At the risk of becoming typecast as ‘that Royal Society librarian who always blogs about expeditions going horribly wrong’, here’s another pear-shaped and lurid tale I found while digitising images for our forthcoming online picture library.

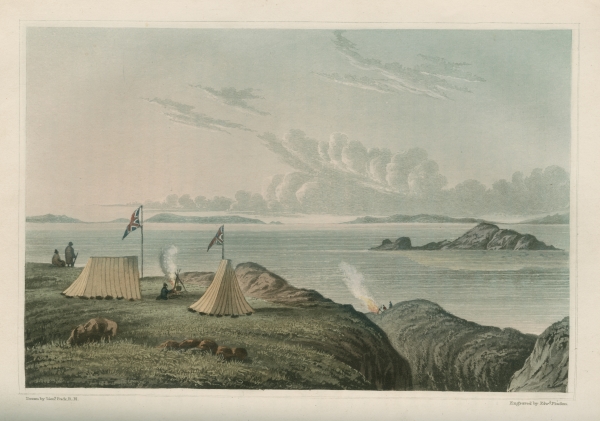

'View of the Arctic Sea, from the mouth of the Copper Mine River, midnight, July 20 1821' by midshipman George Back

With elements of both horror and sheer incompetence, the story of John Franklin’s 1819-22 Canada expedition sits, in my recent armchair travels, somewhere between the sadness of Taiata’s death in Batavia and the light relief of Charles Forbes and his shredded ptarmigan. Franklin survived (just!) to tell his tale, published as the ‘Narrative of a Journey to the Shores of the Polar Sea’ (1823), in which his words are accompanied by many vivid images of the Canadian North and its inhabitants. This landscape shown here, ‘View of the Arctic Sea, from the mouth of the Copper Mine River, midnight, July 20 1821’ by midshipman George Back, appears particularly idyllic – a late supper cooking over the campfire, Union Jacks flying above the tents, and the long-awaited vista of the great expanse of open water in the distance. However, reaching this point had been an endeavour fraught with difficulty … and much worse was to come on the return journey.

The expedition – part of a wider British attempt to find and map the fabled North-West Passage – was intended to travel overland to the Great Slave Lake, follow the Coppermine River northwards along a previously charted route and then, on reaching the sea, turn east and explore Canada’s unknown Arctic coast. Traders from the Hudson’s Bay Company and the North West Company, native tribal and Inuit guides, and Canadian porters (known as voyageurs) were all expected to provide assistance en route.

Starting from the shores of Hudson Bay in August 1819, the expedition took nearly a year to travel the 1700 miles to the Great Slave Lake, hampered by exceptional cold, food supply problems and an ongoing dispute between the two fur trading Companies. The winter of 1820-21 was spent at the encampment of Fort Enterprise on the banks of the Coppermine, where the British party hunkered down alongside argumentative voyageurs and a group of hunters from the local Yellowknife tribe. The daughter of one of the hunters, a comely 16-year-old nicknamed Greenstockings, inflamed the passions of both George Back and his fellow midshipman and artist, Robert Hood, to the point where a duel with pistols was only narrowly averted.

By June 1821, the weather had finally improved enough for Franklin and his men to head off up the Coppermine. On reaching the sea, they set up the camp shown in Back’s illustration, and the Yellowknives headed back to their homes, leaving a party consisting of Franklin, Back, Hood, Doctor Richardson and Ordinary Seaman Hepburn, plus fifteen voyageurs. Launching out to sea in three canoes, they headed eastward and managed to map over 500 miles of uncharted coastline. The plan was then to retrace their route to the mouth of the Coppermine and reach Fort Enterprise before the long Canadian winter closed in; however, rough seas prevented this, and Franklin realised that his men were now facing an arduous land journey back across the aptly-named ‘Barren Lands’.

A flavour of this desperate march can be gained by picking a few random phrases from Franklin’s account: “We were detained all the next day by a strong southerly wind and were much incommoded in the tents by the drift snow” … “Our blankets did not suffice … to keep us in tolerable warmth; the slightest breeze seeming to penetrate through our debilitated frames” … “We perceived our strength to decline every day, and every exertion began to be irksome” … “After our usual supper of singed skin and bone soup”. Even these scraps, scavenged from half-eaten carcasses along the route, often proved elusive, and the travellers were reduced to a diet of ‘tripes de roche’ (an acrid lichen which caused severe diarrhoea) and – famously – their own spare boots, lightly boiled.

Franklin reached Fort Enterprise on 12 October 1821, only to find it empty of the dried meat supplies promised by the Yellowknives. Meanwhile, at the back of the straggling expedition, Hood and Richardson, too weak to continue, had made camp with Hepburn and a voyageur named Michel. The three other voyageurs in Michel’s party had disappeared, and Hood and Richardson’s suspicions were aroused when Michel suddenly began presenting them with copious supplies of “wolf” meat from his secret larder in the woods. Michel and Hood quarrelled; Richardson, rushing back to camp on hearing a gunshot, found Hood lying dead – an “accident while Hood was cleaning his gun”, according to Michel. As this was patently impossible – the gun barrel was long and the bullet had entered the back of Hood’s skull – Richardson’s doubts about Michel were confirmed and, after conferring with Hepburn, he waited for the right moment and shot Michel with his pistol.

The (ahem) “wolf” meat seems to have given Richardson and Hepburn the strength to press on to Fort Enterprise, where they found Franklin and the advance party in a shocking state: “… the ghastly countenances, dilated eye-balls, and sepulchral voices of Captain Franklin and those with him were more than we could at first bear”. More voyageurs were to die of hunger before, on 7 November, relief finally arrived in the form of a party of Yellowknives bearing food. After being nursed back to health, the British party began the long return march, reaching Hudson’s Bay Company headquarters at York Factory in July 1822. Back home, fame and election to the Royal Society followed for Franklin; a murder enquiry into the death of Michel, meanwhile, was quietly dropped, and the expedition’s failure to map more than a short length of Canada’s Arctic coast was lost in tales of courage in the face of extreme adversity.

John Franklin’s ‘Narrative’, an immediate bestseller on its publication in 1823, still makes for a thrilling read – we’ll be happy to show you the original if you pay us a visit, and you’ll soon be able to view more of Back and Hood’s drawings in our online picture library. We’ve also added a couple of modern works on Franklin to our loan book collections – a novel in the ‘Fellows in Fiction’ section, and a fascinating recent study by Andrew Lambert of Franklin’s lost expedition of 1845, re-examining the posthumous reputation of the controversial “man who ate his boots”.