Historian of photography Rose Teanby describes her collaborative investigation, with photographer and fellow researcher Graham Harrison, into one of the most beautiful treasures in the Royal Society Library collection: the cyanotypes of algae created by Victorian photographer Anna Atkins.

In October 1843 a package of cyanotype photographs was delivered to the Royal Society. It had not been donated by the inventor of photography William Henry Fox Talbot FRS (1800-1877), or the inventor of the cyanotype photographic process Sir John Herschel FRS (1792-1871). The collection of stunning blue and white photographs was the gift of a Mrs Atkins of Halstead, Kent.

Anna Atkins (1799-1871) eventually contributed three volumes containing over 400 photographic images, completing Photographs of British Algae, Cyanotype Impressions by 1853. The ten-year project reserved her a place not only within the gift register of the Royal Society, but also in photography’s hall of fame. This donation was the first photographically illustrated book, preceding Talbot’s Pencil of Nature, published in 1844.

The Royal Society Library and Archives are an accessible treasure trove of scientific history. It is quite easy to lose yourself in obscure books of 1827 Society meeting reports or carefully preserved letters to Fellows exchanged two centuries ago. The register of gifts is another intriguing repository of generosity from individuals wishing to donate their contribution to scientific progress. This is where Anna Atkins made photographic history. Looking through the gift register from 1831 to 1844, it was clear that donations from women were extremely rare.

In a previous visit to the Royal Society Library I had researched the extensive correspondence of Sir John Herschel, particularly in connection with stereoscopic photography of the moon. Herschel’s many photographic interests included the invention of the cyanotype process in 1842. The method was adopted by Anna, and by the following year she had produced the first part of the volume we had come to see.

I booked to view these original photographic treasures at the Royal Society Library in November 2017 with my fellow researcher Graham Harrison. We hoped to photograph her books for use in a lecture I was to present at the National Portrait Gallery, and to illustrate an article to appear on Graham’s website. Access to such a rare, valuable artefact was indeed a privilege, but nothing can prepare you for the impact these images make.

© Graham Harrison

The exhibition case alarm system was temporarily disabled, and Library manager Rupert Baker retrieved the first of Anna’s three volumes. It had been inscribed in October 1843 with the words ‘For the Royal Society, Presented by Mrs Atkins’. The first page was dedicated to her father John George Children FRS (1777-1852) who had nurtured Anna’s artistic and scientific interests from an early age.

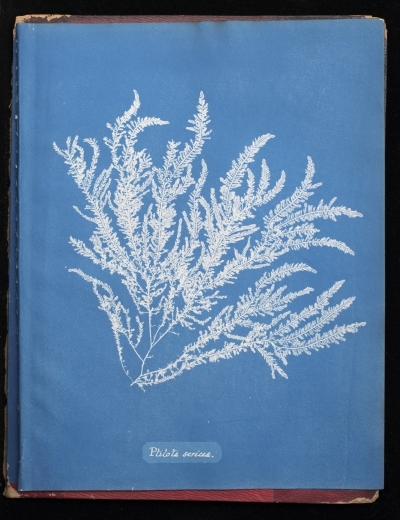

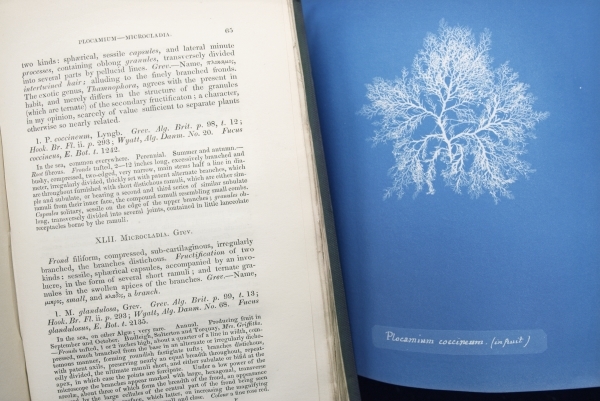

Anna’s cyanotype photographic images were created as an accompaniment to William Henry Harvey’s 1841 book A manual of the British Algae. Harvey – later elected FRS, in 1858 – had compiled a definitive reference guide to British algae but the book contained no illustrations. So Anna produced a volume of the images that Harvey’s book lacked, which corresponded as faithfully as possible to his 1841 guide.

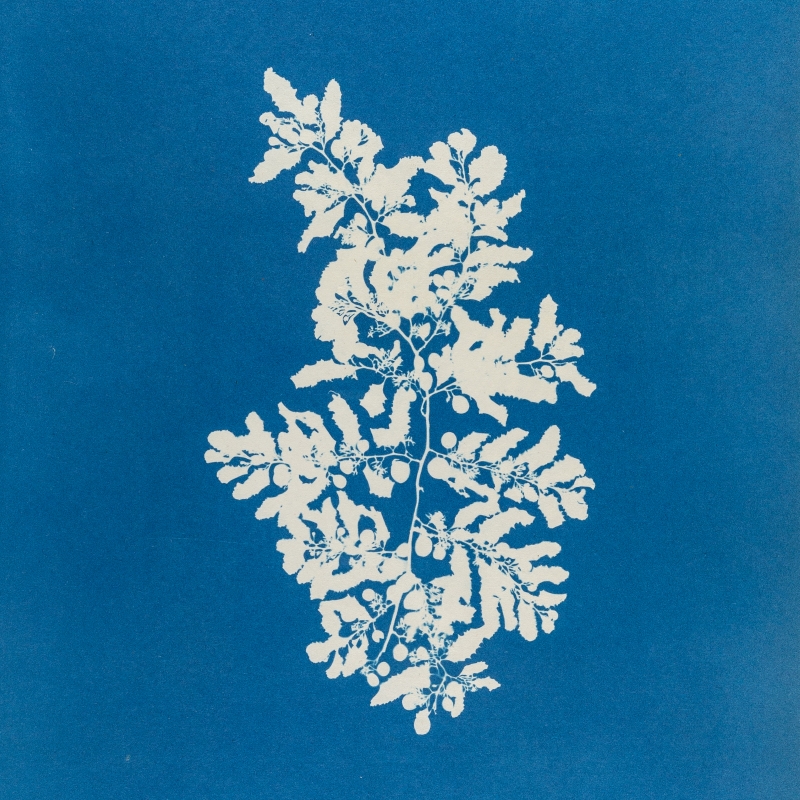

Anna was a keen botanist and combined her knowledge with the new art of cyanotype photography. Each specimen of algae had been carefully placed onto paper coated in iron salts, then exposed to light, then washed in water. A white negative image remained where the specimen of algae left its delicate profile against a background of deep Prussian blue, as distinctive as Wedgwood Jasper.

The book in front of us contained page after page of vibrant cyanotypes of her ‘flowers of the sea’, as visually stunning as the day they were brought into being by the 1843 Kent sunshine. To be edged in gold seemed entirely appropriate for a book of such value to the history of photography.

© Graham Harrison

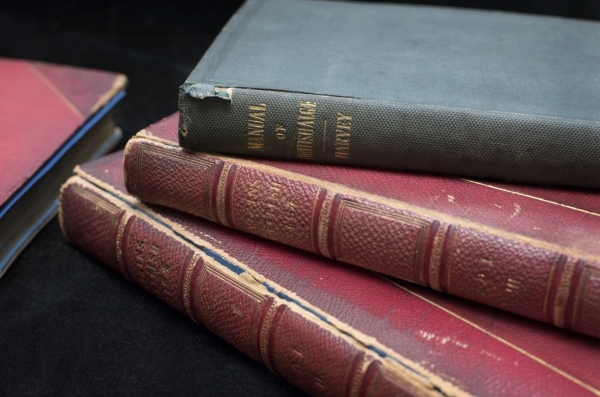

Many archives restrict camera use but the Royal Society supported careful photography of Anna’s fragile volumes. Graham captured several images during our November visit but a second visit was necessary to complete our list. In January 2018 we returned, politely asking the impossible: could we photograph all three volumes plus Harvey’s original 1841 British Algae together? There is no record of a similar Royal Society photograph and we were given permission to assemble this priceless collection of books.

Photographs of British Algae, Cyanotype Impressions by Anna Atkins, with A manual of the British Algae (1841) by William Henry Harvey. Photo © Graham Harrison

Photographs of British Algae, Cyanotype Impressions by Anna Atkins, with A manual of the British Algae (1841) by William Henry Harvey. Photo © Graham Harrison

Rare books are usually issued individually so this was a generous gesture. We also wanted to photograph one of Harvey’s descriptions of algae with the corresponding cyanotype impression in Anna’s work. This entailed finding an entry on a right-hand page of Harvey’s volume that corresponded with an appropriately sized cyanotype image in Anna’s book.

© Graham Harrison

On 3 May I delivered the National Portrait Gallery lecture Who was Britain’s First Female Photographer? Anna’s photographs took centre stage and looked sensational. Her vivid blue cyanotype specimens were in sharp contrast to the pervading sepia tones indicative of the early days of photography. These images introduced vibrant colour into a monochrome world, something hard to comprehend with the mass of full coloured images we now see daily.

The Royal Society has been the birthplace of innovation and discovery since 1660. It also became the birthplace of photography in January 1839 when William Henry Fox Talbot announced his invention of photogenic drawing. Photography has evolved from Talbot’s 1839 announcement into an essential part of daily life, making a world without photographs hard to imagine.

In recent years Anna’s cyanotype images, combining botany with photochemistry, have assumed a new status as individual works of art. But on that cold, rainy January 2018 day, the Royal Society made it possible for modern digital photography to be re-focused on its extraordinary heritage. Anna’s gift of 1843 burst into life once again, resuming its place beside Harvey’s British Algae, bringing shape and colour to his words, exactly as she intended 175 years ago.