Keith Moore untangles the threads linking writers Alfred Jarry and Geoffrey Household with Royal Society Fellows C.V. Boys and J.G. Frazer.

It wasn’t just Edward Lear’s Jumblies who went to sea in a sieve. Another madcap fictional mariner, Doctor Faustroll, took to the waves in a perforated copper boat supported by surface tension alone. He also boasted a shirt and skiff made from quartz fibres, threads that were quite the latest thing in scientific hardware at the turn of the twentieth century.

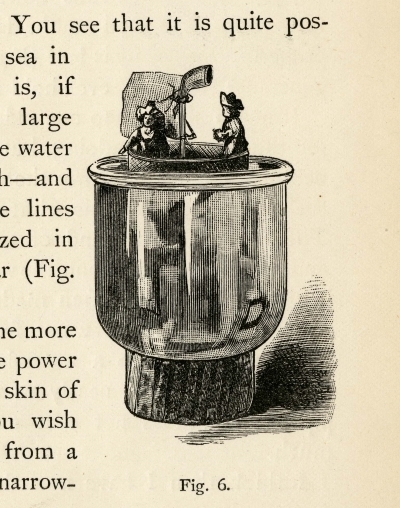

Sailing a sieve, from Soap Bubbles (1890) by Charles Vernon Boys

Given that the inventor of superfine quartz fibre suspensions for radio-micrometers and the like, Charles Vernon Boys FRS (1855-1944), would charge one guinea per instrument part, that makes the skiff imagined by the French surrealist Alfred Jarry (1873-1907), quite up there with the most expensive of modern super-yachts. And how would you begin to use the near-invisible crystalline threads to build a boat? That’s not the only piece of absurdist fun to be had from Jarry’s final book, Exploits and Opinions of Dr. Faustroll, Pataphysician, posthumously published in 1911. The playfully warped fantasy is packed with ideas filched from scientists of the day – Lord Kelvin, William Crookes, John Tyndall and others; but most often from Boys, himself the author of a weird and wonderful book of popular science, Soap Bubbles (1890).

If you’ve come across Jarry before, it may be second-hand, via English surrealist writers such as Angela Carter and J G Ballard. I’m now officially adding Faustroll’s exploits to my recommendations for summer reading. But if you’d like to have a classic British thriller instead, then Geoffrey Household’s Rogue Male (1939) might be the thing for you. Just as Jarry owed a debt to the colourful C.V. Boys, so Household took inspiration from another Royal Society Fellow, this time one with a flair for the dramatic – the anthropologist James George (‘J.G.’) Frazer FRS (1854-1941).

Rogue Male begins with that most essential feature of a good read – a simple but brilliant premise. It is 1939 and a man with a rifle stalks a European dictator. Now of course we know what didn’t happen in Germany. But having set up a why-didn’t-anyone-think-of-that plot line, the book veers into some very strange territory, as the protagonist, an aristocratic big-game hunter, escapes Nazi assailants before going to ground in Dorset, dogged by an equally skilled hunter-adversary.

Mistletoe cover design from J G Frazer’s The Golden Bough

J.G. Frazer’s classic work was the book The Golden Bough (1890) a serious and encyclopaedic set of researches into ritual and magic, which opens with a thriller-like flourish. Frazer was inspired, he wrote, by an attempt to understand the curious and savage priesthood of the Temple of Diana at Nemi in Italy. Here, Diana’s priest would guard a sacred grove, but lived as a king of the woods, in fear of being murdered and replaced by a novitiate carrying the eponymous golden bough.

I won’t tell you how that story ends either – really, you should read some books – but the theme and landscape of Geoffrey Household’s Dorset is that of Frazer’s ancient Italy, where woodlands and lakes are both sacred and lethal and where two men contest the grove dedicated to a very modern Diana.

Apart from their scientific undercurrents, there is a curious, entirely coincidental connection between the two books. Jarry was quite familiar with how Charles Vernon Boys made his quartz fibres, and mentioned the technique. It was a fascinating collision of medieval technology and cutting-edge physics as Boys would fix a quartz rod to a crossbow bolt, heat the quartz, and then fire the bow to draw out the fibre. Household’s thriller is resolved by his hero’s knowledge of ancient Roman ballista and their construction, allowing him to build a crossbow (the details are too gruesome for this blog, gentle reader) with which to cast his equivalent of the golden bough of antiquity.

Two books, two bows and two Fellows – it all adds up to some great reading, with just a little thread of science attached.