A new addition to the Royal Society Library's book collection tells the story of Elias Ashmole FRS, alchemist, antiquarian, botanist and freemason.

We’ve just acquired a copy of a book by one of our earliest Fellows, Memoirs of the life of that learned antiquary, Elias Ashmole, Esq; drawn up by himself by way of diary (1717):

While tiny in size – I had to trim our standard Royal Society bookplate to fit the inside of the front cover – the book documents the life of a larger-than life character, whose name you’ll doubtless recognise if you’ve visited a certain museum in Oxford.

Elias Ashmole (1617-1692), from Newtoniana Volume II p.151 (MS/648).

Elias Ashmole was born in Lichfield on 23 May 1617, at ‘3 Hours 25 Minutes 49 Seconds A.M. … the Quarter 8 of II ascending’. This precise entry on page two of the Memoirs hints at his lifelong interest in astrology; indeed, he name-drops the seventeenth-century equivalent of Mystic Meg in his next sentence: ‘Mr Lilly's Rectification thereof, Anno 1667 … makes the Quarter 36 ascending.’ As further proof of Elias’s astrological – and alchemical – leanings, here’s an image from a 1652 book already held in our collections, his (deep breath) Theatrum chemicum Britannicum: containing severall poeticall pieces of our famous English philosophers, who have written the Hermetique mysteries in their owne ancient language:

The Memoirs cover the 75 years of Ashmole’s life at an average of just over a page per year, so they fairly race along. Elias himself seems to have been somewhat accident-prone: smallpox, swinepox and measles on page two, a nasty gash to the knee on page three, and a particularly rough time in 1647-8 when he suffered successively from ‘Boyles’, a violent fever, a Quartan Ague and Phlegm, and was robbed in Maidenhead Thicket on a journey to London. And you can see why the first objective on Robert Boyle’s ‘to-do list’ is the prolongation of life, as many pages of the Memoirs feature a premature death, notably Elias’s first wife, who died while pregnant only three years after their wedding.

Elias’s second marriage, to the wealthy and thrice-widowed Lady Mainwaring, took place in 1649. After much legal wrangling, on 11 February 1652 he records that ‘the Statute of 3000 l. [£3000] and Mr. Stafford’s Counterpart of his Lease of my Wives Jointure was delivered to me, by direction of [first husband] Sir Arthur Mainwaring’s Lady, who had been trusted with it.’ This huge sum left Elias free to pursue his interests in alchemy, botanical classification, freemasonry and antiquarianism, all of which feature with increasing frequency in the Memoirs.

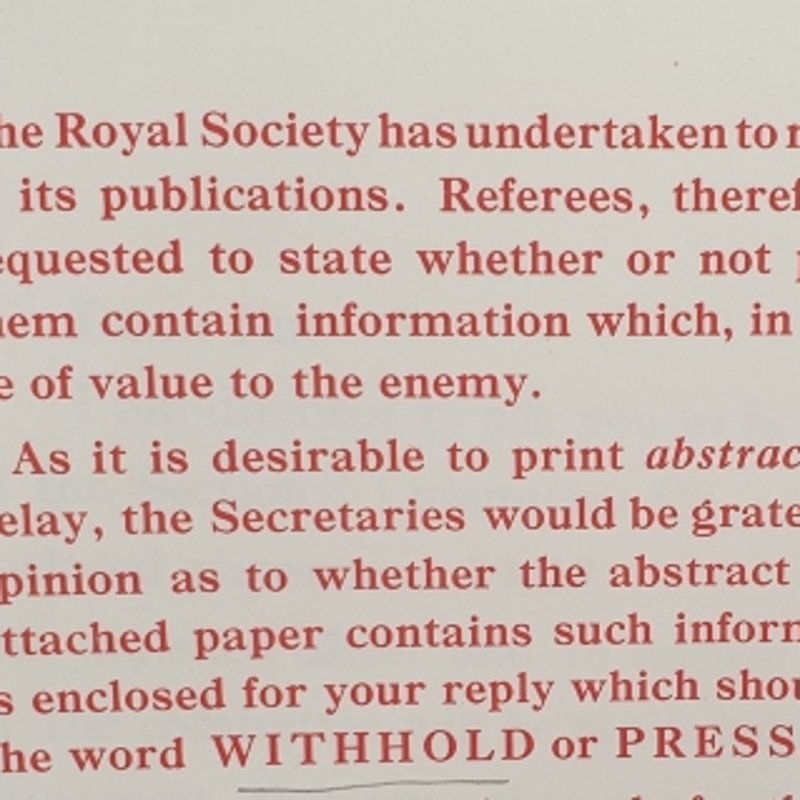

We also find Ashmole falling into good company: on 14 June 1652 ‘Dr. Wilkins and Mr. Wren came to visit me at Black-Fryars, and this was the first time I saw the Doctor.’ It was certainly not the last: on 28 November 1660, when Wren and Wilkins were among the twelve natural philosophers who pledged to form a college ‘for the promoting of Experimentall Philosophy’, Ashmole’s name is on the list of 41 persons ‘judged willing & fitt’ to join (below), and he notes that on 15 January the following year, ‘I was admitted to the Royal Society at Gresham-College’. Within a month or so either side of this date, the Memoirs also record that he was admitted to the Bar, took an oath as Comptroller of the Excise, and was appointed ‘Secretary of Surinam in the West-Indies’ – a busy man indeed!

Excerpt from the minutes of the first meeting of the Royal Society, 28 November 1660 (JBO/1 p.2).

The lack of subsequent mentions of the Royal Society does rather support Professor Michael Hunter’s categorisation of Ashmole, in his monograph on the early Fellows, as ‘barely active’. He’s also not a patch on Samuel Pepys in his coverage of great historical events – the entry for 2 September 1666 reads simply ‘The dreadful Fire of London began’, with the next, more than a month later, recording in much greater detail how he got some of his books back from his cousin.

Nonetheless, despite the later pages of the Memoirs cycling between a diminishing range of topics – social climbing and financial improvement, legal disputes, and further ailments (so much gout!) – we’re pleased to add it to our collection of books on our early Fellows. There are darkly intriguing snippets on how Elias came to acquire the contents of ‘Tradescant’s Ark’, the famous Vauxhall collection of curiosities that formed the nucleus of the Ashmolean Museum when it opened in Oxford in 1683. The deed signed by Tradescant the Younger, giving the collection to Ashmole, was contested by Tradescant’s widow, who held the collection in trust until, as Elias notes in spring 1678, at precisely ‘11 Hor. 30 Minutes ante merid‘:

‘Apr. 4. … My Wife told me, that Mrs. Tredescant was found drowned in her Pond. She was drowned the Day before about Noon, as appeared by some Circumstance.’

‘22 [April]. I removed the Pictures from Mrs. Tredescant’s House to mine.’

Hmmm, let’s just leave the story right there, shall we?