Archivist Virginia Mills examines Humboldt's role in establishing a network of magnetic observatories across the world, and his philosophy that everything in nature is interconnected.

This is the year of Humboldt! Baron Friedrich Wilhelm Heinrich Alexander von Humboldt ForMemRS, to give him his full name, and this September marks the 250th anniversary of his birth.

Humboldt was something of a celebrity in his own day, and the centenary of his birth was widely commemorated. However, in the intervening years between that jubilee and this, he has perhaps been somewhat neglected; certainly he is no longer a household name despite the fact that he was influential across so many disciplines. He determined the magnetic equator, laid the foundations of biogeography, made the first scientific explorations of South America, gave us the modern use of the word ‘Cosmos’, espoused romantic philosophy, and was the first to describe human-induced climate change. And he has a penguin named after him.

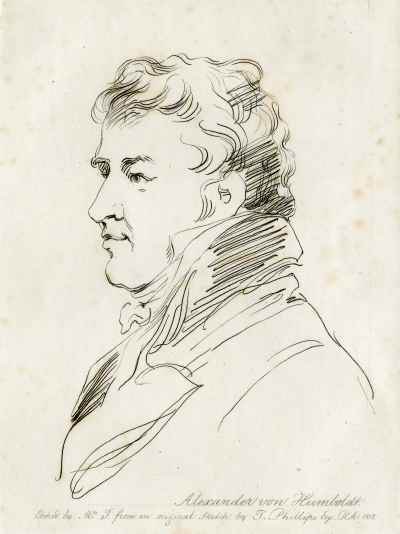

Portrait of Alexander von Humboldt, engraving by Harriet Turner after Thomas Phillips, 1815

Humboldt is justifiably being celebrated and remembered in the year 2019 amidst wider recognition of the relevance of his scientific worldview – the belief that everything in nature is interconnected. I’ve pulled out one document from the Royal Society’s archive that I think highlights some Humboldtian principles that resonate today:

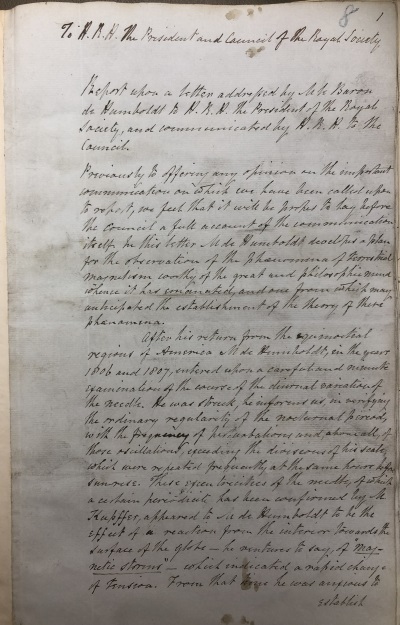

Report for the Royal Society Council on Humboldt’s letter (AP/20/8)

The document is a letter on terrestrial magnetism written by Humboldt to the President of the Royal Society, HRH the Duke of Sussex, in 1836. Humboldt’s aim was to secure the Royal Society’s cooperation in establishing a network of magnetic observatories across the world, with ‘apparatus similar to his own … in order to obtain corresponding observations made at great distances at the same hours.’

Humboldt hoped that this would allow him to determine the causes of disturbances in the earth’s magnetic field that he called magnetic storms. But more than this, he recognised the need for collective scientific endeavour to gather a uniform data set comprised of comparable concurrent observations from different continents, in order to make possible the extrapolation of ‘great physical laws … which govern some of the most interesting phenomena in physical science.’

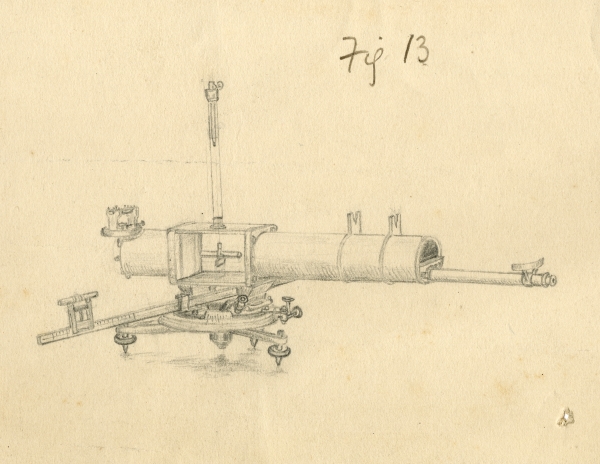

Study of a magnetometer, an instrument used to measure the strength of the Earth’s magnetic field, by William Fletcher Barrett. Used in Barrett’s book Outlines of magnetism and electricity (London, Bell & Daldy, 1871). MS/377/2/3/5/10.

Using his own vast network of correspondents, by 1836 Humboldt had already established permanent magnetic observatories across Europe and Russia, stretching from Paris to China. Having been elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society in 1815, Humboldt was also well placed to appeal to the Society to use their influence and international Fellowship to include observation stations in the British dominions.

The letter was considered important enough for the Royal Society to set up a committee specifically to formulate a response. The unimaginatively-named ‘Committee for Considering the Letter of Baron Humboldt’ only recorded minutes for a single meeting, but they did decide to cooperate with Humboldt’s request. British Colonial observatories were set up in Toronto, Singapore, Simla and Madras, and during James Clark Ross’s Antarctic expedition (1839-1843) he established observation stations in St Helena, the Cape of Good Hope, Hobart Town, Kerguelen, Auckland Island, New Zealand and the Falkland Islands.

In a 1991 article, S.R.C. Malin and D.R. Barraclough stated that ‘the network … that currently monitors the geomagnetic field … can, with some justification be said to owe its existence to Humboldt’s efforts in organizing simultaneous observations for the study of magnetic storms’. Considering the significance today of magnetism on communications and navigation technology, this is quite a legacy.

Humboldt as an organiser of international scientific endeavours reminds us that collaboration was and remains essential to science, and that this has always been one of the functions of the Royal Society, founded in part to gather knowledge and empirical evidence from around the world. From the Society’s first major internationally collaborative scientific effort – the observation of the Transit of Venus in 1769 – to modern examples of data-sharing such as the array of telescopes that made the first black hole photograph possible earlier this year, Humboldt’s magnetic observatories fit into a rich history of scientific collaboration, and long may it continue.

Humboldt penguins

Further reading

To find out more about Humboldt, check out Andrea Wulf’s book The invention of nature: Alexander von Humboldt’s new world, winner of the 2016 Royal Society Insight Investment Science Book Prize.

Activities to commemorate Humboldt’s 250th birthday can be found on the website of the Humboldt Foundation, Berlin: https://avhumboldt250.de.