As our copy of Robert Hooke's 'Micrographia' goes off for conservation, we look at the printing history behind the book's iconic images.

It seems fair to say that Robert Hooke’s Micrographia is one of the most iconic volumes of our collections. As it illustrates what is invisible to the naked eye, it gives us a taste of the effervescent reinvention of the ways of seeing and understanding the world which took place in early modern Britain.

As one of the earliest and definitely most successful Imprimaturs of the Royal Society, it establishes the importance taken by scientific communication from the earliest days of the Society. We also know that Hooke played a crucial role in shaping the early activities of the Society, not least as Curator of Experiments.

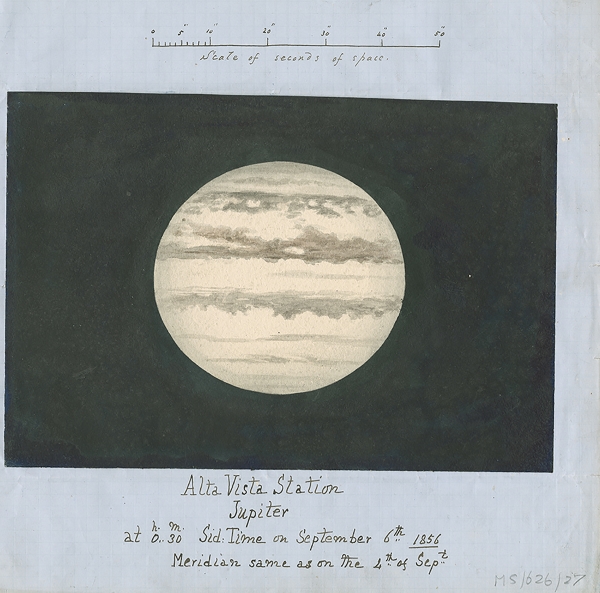

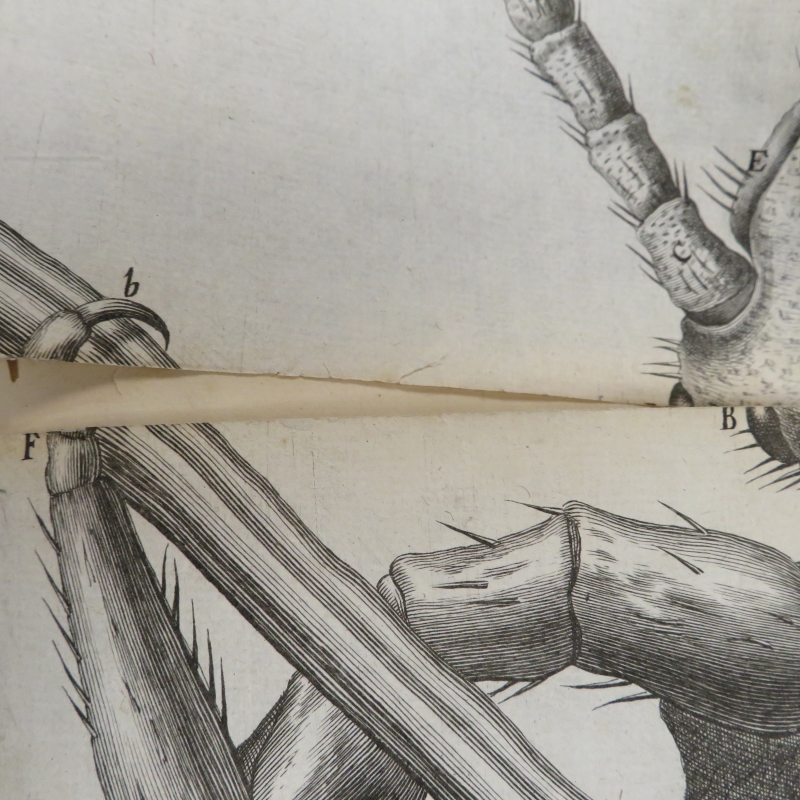

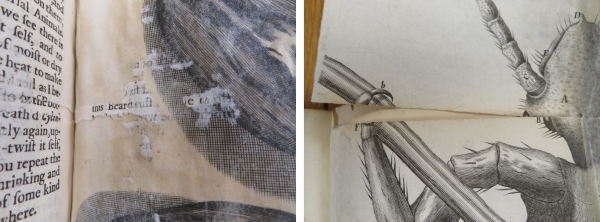

The Royal Society’s first edition, published in 1665, is therefore often requested by readers, put on display (most recently in the aptly-named Science Made Visible exhibition) or showcased in our ever-popular show-and-tell tours. With such heavy use comes some wear and tear. The fold-out plates, which made the book into a bestseller, are in particular quite damaged and it seems that previous inappropriate attempts to preserve the book led to some tears. It was time then for Micrographia to get a bit of a clean!

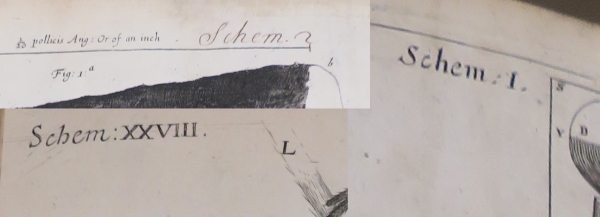

Example of damage to plates

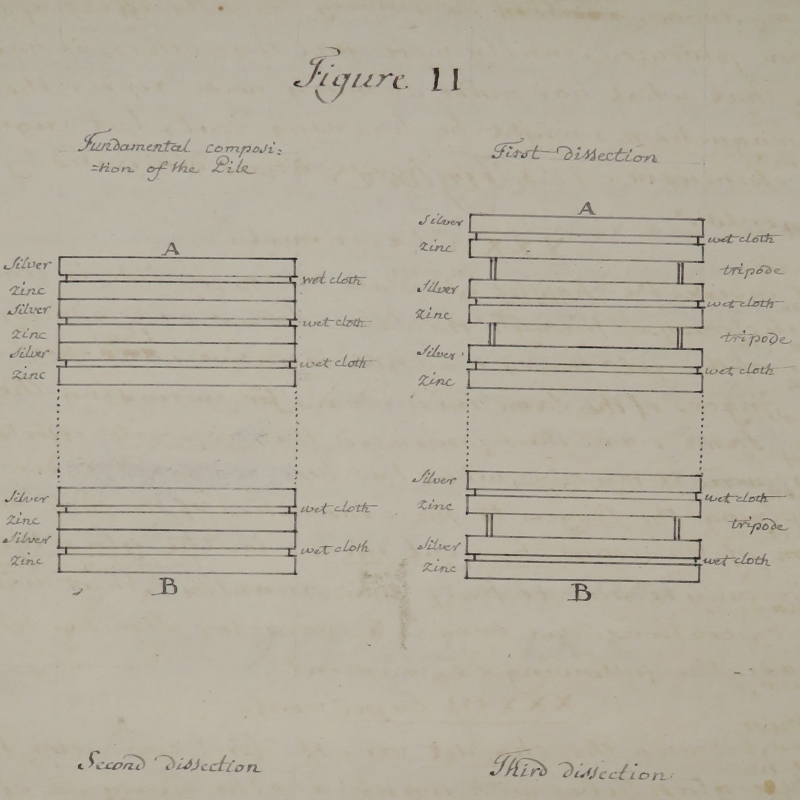

A few weeks ago, we therefore entrusted our paper and binding conservator Sarai Vardi with our precious volume so that she would surface clean the pages, consolidate brittle edges, mend the tears and re-fold the folds. One of the first steps to any conservation job is for us to write what is poetically termed a ‘condition report’. In the process of writing my report, I paid particular attention to the plates. After describing the damage to a few of the plates, I noticed that the lettering of their titles differed dramatically from plate to plate:

Some of the five types of lettering found on the plate titles, including a handwritten addition for Schema 2

The success of Micrographia means that plates were engraved for various editions, reproduced and copied. I knew from other copies that it can be quite challenging to make any definitive assertion as to which prints were printed as part of the first edition. So far as I know, no scholar has written anything regarding the printing enterprise behind the bookseller or put together a guide to identify individual plates.

The notion that there would be a ‘true’ and ‘definitive’ first edition, has long been challenged by book historians who know too well that the printing process involved so many hands and heads that attributing definitive authority to a single copy other than a signed author’s manuscript is a tricky claim to make. I had no doubt, however, that the copy donated by the author to the Royal Society would include a complete suite of the very first engraved plates. Yet, the remarkable differences in lettering seemed to signal something interesting about the making of the book. So here are my proposed explanations:

The plates were all prepared for the 1665 edition, under the supervision of booksellers John Martyn and James Allestry, but:

(1) The plates were engraved by a single engraver, then sent back for lettering to a single printer, who (for whatever reason) chose completely different sets of letters from title to title and forgot to letter a few.

(2) The plates were engraved by a single engraver, but sent to different printers who were working as a syndicate for the making of the book, under the supervision of the well-connected Martyn.

(3) The plates were engraved by different engravers, who sent back each set of plates for lettering to the printer at slightly different times, which means that the printer was then using different sets of types depending on the current project being working on.

(4) The plates were engraved by different engravers, who each lettered (or not) the plates using the types they had available in their workshops.

I would think option (3) is most likely, but whatever the explanation, one thing is sure: Micrographia will not stop surprising.

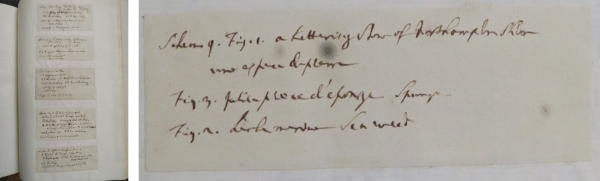

Another surprise indeed came from the back pages, which included handwritten description of most plates in an unknown hand. Could it be the titles sent to accompany the plates to the printer? Or an early modern reader trying to make sense of the plates? Then, who added the manuscript strips to the printed copy? All I can say at this point is that the strips were definitely (re?)mounted at the time of rebinding in the twentieth century. In any case, adding loose manuscripts at the end of the volume, nowhere close to the plates they refer to, seems an odd choice to make when there is an archive full of related papers.

Handwritten slips

For sure, I will reach out to our favourite Hooke expert, Dr Felicity Henderson, to solve some of those mysteries and I very much look forward to seeing the flea restored to its former g(l)ory.

Note to readers, Micrographia will be available to the public from 4 November, cleaned up. Beware, though – you might still find the odd moth, louse or flea lurking within its pages.