Keith Moore takes a look at the secret love messages hidden in Victorian flower bouquets, and the pioneering iris cultivation work of Royal Society Secretary Sir Michael Foster.

I had some awareness of the Victorians’ mild obsession with reading coded meanings into gifts of flowers, but I’ve been slow to pick up on the notion that it was all the fault of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu (1689-1762).

Lady Mary is very familiar to us, of course, for her pioneering work in introducing inoculation against smallpox to Britain. Her open-minded Italian physician Emanuel Timoni (1670-1718) aided her in Constantinople and wrote to the Royal Society about the local practice of disease protection. But by 1718, Lady Mary penned a very different letter to a friend, referring to the Turkish custom of linking small objects (including flowers) to poetry, thereby creating a shared secret language. She explained that: ‘There is no colour, no flower, no weed, no fruit, herb, pebble, or feather, that has not a verse belonging to it; and you may quarrel, reproach, or send letters of passion, friendship, or civility, or even of news, without ever inking your fingers.’ The published version of her Turkish letters (1763) is said to have popularised the idea.

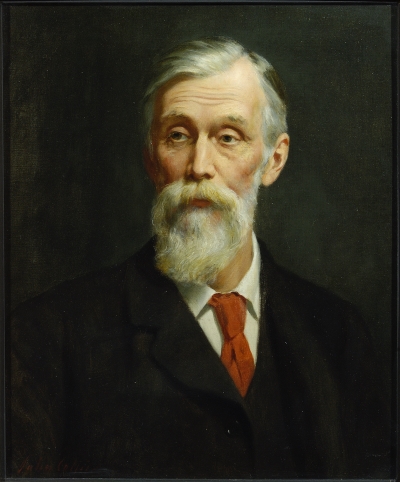

I have to say, I’m mildly sceptical about this – why did it take so long to catch on? True or not, by the nineteenth century there were many guides to outlining the love-messages that might be sent via ‘talking bouquets’ sometimes known as tussie-mussies. Quite how anyone figured out the variable meaning of such things is beyond me. My own favourite flower, the iris, seems to have half-a-dozen different interpretations, so I would have been a very confused and lovelorn Victorian. However, there was one period scientist who was very keen to explore some of the secrets of irises: the Royal Society’s secretary, Sir Michael Foster (1836-1907).

Michael Foster, by John Collier, c.1908

In a business letter from 1895 that I noticed within the Royal Society’s archives recently, which prompted a little research, there is a brief personal note to Foster from his assistant Herbert Rix. Rix mentions in passing that he has some iris bulbs in a drawer for Foster, sent by a Dr Sclater (probably Philip Lutley Sclater FRS) and he is liable to forget them during the Society’s anniversary meeting.

Now Michael Foster wasn’t a botanist. He was a physiologist, specializing in heart muscle, and a university teacher by profession. Iris collecting and breeding was his passion and one linking him with the greatest scientist of his era, Charles Darwin. Darwin wrote about the problems of cross-pollination and the fertility in plants and hybrids in several of his books. He experimented in his own garden at Down House and wrestled with the hidden meaning of their still secret genetic codes. Therefore, it’s easy to see Foster’s hobby as a private tribute to the great man, one of reciprocated curiosity.

Foster became one of the leading lights of iris cultivation, both identifying new varieties from the wild, and creating new types of hybrid for commercial flower catalogues. His very readable articles appeared in The Gardener’s Chronicle and elsewhere. Foster named many varieties, some of them after Darwin family members of his acquaintance – there was a Charles Darwin iris (tall and bearded, naturally) and hybrids named for Mrs Horace Darwin and Mrs George Darwin.

Iris xiphiodes, by Arthur Harry Church, 1907

Meanwhile, the iris was about to have an even more curious connection to hidden information. Another expert in hybridization, the American botanist Edgar Shannon Anderson (1897-1969) had spent his early career in the Twenties and Thirties gathering information on regional iris varieties in the United States. A short study visit to England brought him into contact with the statistician Ronald Fisher FRS (1890-1962). In 1936, Fisher produced a short, but hugely influential paper from Anderson’s fieldwork on three different species of wild iris. Fisher took the measured physical characteristics of specimens collected on the same day and combined them into a classic dataset, with a view to distinguishing (or not) three varieties of iris.

The Iris flower data set (sometimes named after Fisher, sometimes Anderson) has had a long afterlife. The blooms may have faded for getting on a century, but their information lives on, widely used for algorithm testing and training in the field of machine learning.

So, three very different species of scientist finding meaning, both serious and frivolous, in the simplest of spring flowers. Bouquets all round: but what will the messages be?