The Royal Society's Keith Moore examines the illustrations found in Thomas Bewick's books on nature.

A little girl turns the pages of a decorated book in a deserted sitting-room, poring over its frozen vignettes: ‘Each picture told a story; mysterious often to my undeveloped understanding and imperfect feelings, yet ever profoundly interesting…with Bewick on my knee, I was then happy’.

The opening of Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre is one of the most famous and familiar in English novels and the reference to Thomas Bewick’s A history of British birds is perfectly fitting. The engraver’s books – A general history of quadrupeds (1790) and the two volumes that formed the British birds (1797-1804) – would have been found in the libraries of the professional classes and country gentlemen, especially in northern counties, in the early nineteenth century. Cheaper than the lavishly-illustrated natural histories garnished by the hand-coloured copper engraving, Bewick’s books were of a piece with Gilbert White’s Natural history of Selborne (1789). They were deceivingly simple in tone, beautifully executed in form and had intimate and local knowledge of their subjects.

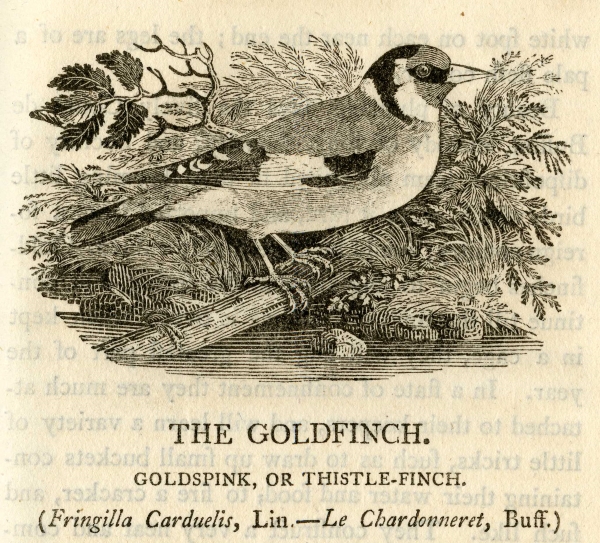

Goldfinch, by Thomas Bewick, from A history of British birds, vol.1 (1797)

Thomas Bewick (1753-1828) of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, perfected an old technique of illustration, using the cross-grain surface of boxwood to reproduce usually small, but highly detailed designs. Before the advent of photography, the method was widely adopted, since the wooden blocks could be used for large print runs and many editions of books without major loss or degradation of the image. Bewick’s mini-encyclopedias of animals and birds were blessed with other advantages. The artist had an enquiring mind and sought out books by previous writers on his subjects, many of them Fellows of the Royal Society. The works of John Ray and Francis Willughby, and George Edwards’s bird etchings, impressed Bewick greatly. The popularity of his Quadrupeds led to offers of help and he took advantage of a network of landowners and collectors, who supplied him with avian specimens for his second natural history project. By then, he had attracted the attention of the naturalist Thomas Pennant FRS (1726-1798) and of Sir Joseph Banks, the Royal Society’s President.

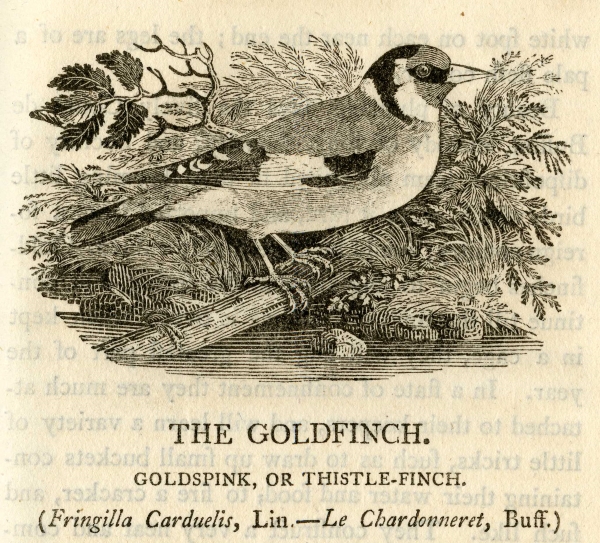

Spoonbill, from A history of British birds, vol.2 (1804)

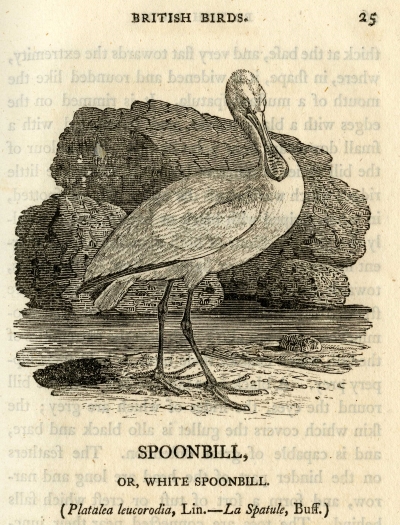

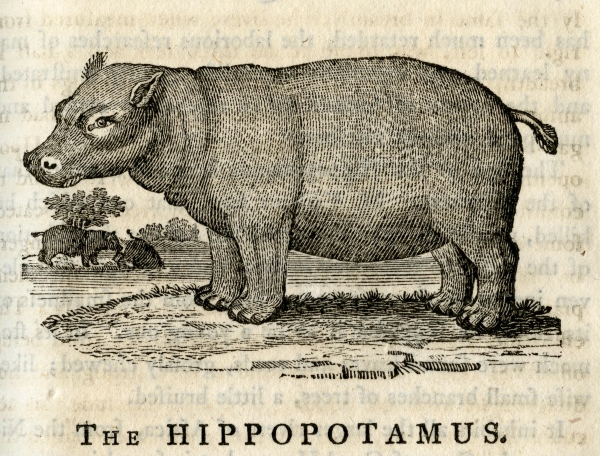

Today, you can view many of his illustrations online, and digital enlargements reveal their detail. But it’s worth picking up a Bewick original from an antiquarian bookshop, to see what the fuss was about – later editions are still affordable. You’ll need an armchair and a magnifying glass, in the manner of an eighteenth-century antiquary (it’s how I see myself), but that’s part of the fun. Notes on the hippopotamus led to a textual lament (by Ralph Beilby, Bewick’s business partner) ‘that suitable delineations have not accompanied their accurate descriptions – a general defect, by which the study of nature has been much retarded … and the errors of former times repeatedly copied, and multiplied without number’.

Hippopotamus, from A general history of quadrupeds (1791)

Hippopotamus, from A general history of quadrupeds (1791)

Thomas Bewick was certainly accurate, but of course there are very few hippos in Newcastle, and therefore one can sympathise with his dilemma in drawing the exotic in natural history. Still, updated editions of his books managed to incorporate the latest finds. From 1798, he was able to draw a nameless ‘amphibious animal’ (the platypus) from New South Wales, thanks to an account sent by the colonial Governor, John Hunter (1737-1821) to the Literary and Philosophical Society of Newcastle.

Bewick was, thankfully, parsimonious when it came to blank paper. His books are famous for their tailpieces, tiny vignettes which had the object of filling in empty spaces at the end of chapters. Therefore, among his block prints of spoonbills, or goldfinches, you will find some unexpected scenes. Most famously, Bewick dealt with country life of the period and these designs might be exercises in miniature storytelling, ribaldry, or plain horror: the child reader of Jane Eyre’s day would have to be tough-minded to view the hanging of a cat, for example.

A gruesome tailpiece: hanging cat, by Thomas Bewick

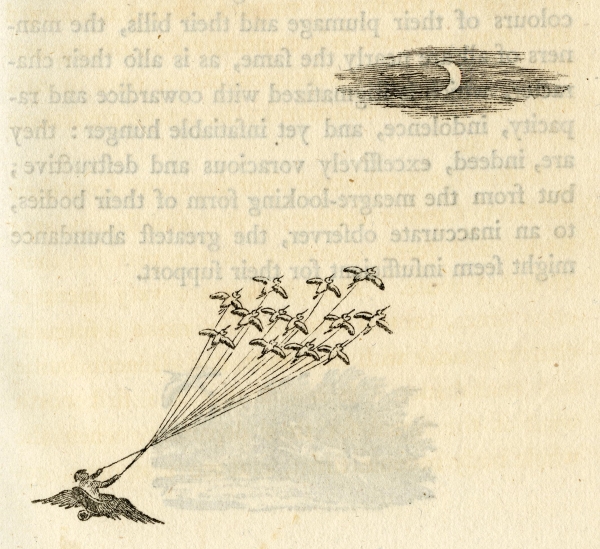

Equally, there are many examples of jeu d’esprit. My particular favourite follows the ‘Crane’ section of Bewick’s British birds where, in a few strokes of ink, the engraver presents a journey to the Moon by swan-led chariot. Here, the print takes its theme from Francis Godwin’s The man in the Moone (1638), sometimes considered an early science fiction story. The young Jane Eyre may have been fascinated by his death-white realms and forlorn regions – but Bewick could certainly make his birds fly from the page.

A flight to the Moon, by Thomas Bewick