The Royal Society's Louisiane Ferlier examines the world of rare book collecting, and how important provenance can be when valuing works.

In the rare book marketplace, the value of a volume has always depended on a variety of factors such as rarity or completeness. In the last 100 years, in an interesting reversal, provenance seems to have replaced more objective criteria such as physical condition in dictating the value of a specific copy.

Gone are the days of crazed Victorian book collectors trimming out marginalia to fit a binding style or removing traces of previous ownership in their quest for a pristine copy! Now, the most expensive books in the world are explicitly valued because of their ownership, and entire research projects are dedicated to establishing the meaning of a smudge or the doodling habits of a reader.

Front pastedown of our copy of Agrippa De Occulta Philosophia (Cologne, 1533), previously owned by Sir Isaac Newton

Front pastedown of our copy of Agrippa De Occulta Philosophia (Cologne, 1533), previously owned by Sir Isaac Newton

Provenance marks – whether bookplates, stamps or handwritten annotations – give the book collector clues to ownership, and provide the scholar with evidence of how a book was really read, valued, used or abused. They guide the book enthusiast through the re-imagined journey of an object: here you see it beginning its life at the printer and the bookseller, there it lies open to collect the spills of the alchemist, now it is scribbled on with crayons by the creative offspring, or later left to collect dust on a packed shelf. For a collection like that of the Royal Society Library, provenance allows us to understand who used its books, who gifted what to the institution in different periods, what topics were considered of interest, and what was deemed irrelevant in the pursuit of science.

Although our online Library catalogue provides a complete list of the collection, little provenance information has so far been captured, even with a wealth of evidence to be discovered in nearly every single book and in the manuscript catalogues I love so much. To investigate how we could improve, on 9 March we held a workshop dedicated to the subject of provenance in the Royal Society’s collections from 1650 to 1750. Rare book cataloguers, book historians and provenance specialists discussed topics such as the libraries of historical Fellows, how some copies from the Royal Society Library found their way into other collections, and how related libraries handle provenance information.

The participants were truly inspiring, leaving Library Manager Rupert Baker and myself with some excellent ideas to implement: gathering information gleaned by readers through a form available in the reading room, creating a chronological list of Royal Society book stamps, and continuing our digitisation of collection catalogues and unique Library copies, to name but three. The general conclusion was to capture as much provenance information as feasible and share it as widely as possible.

As a first step in this direction, here’s one of the provenance stories from the collection that we shared with the workshop participants. It features a 1639 edition of Johann Remmelin’s Catoptrum microcosmicum, a flap anatomy book which tells a cautionary tale of mistaken identities in the quest for provenance.

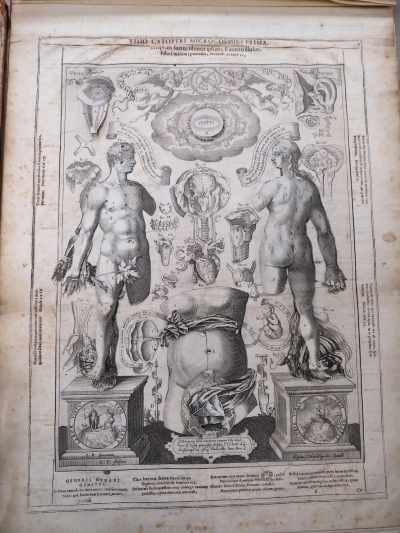

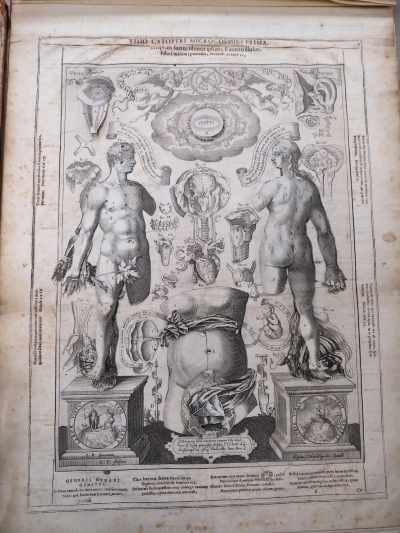

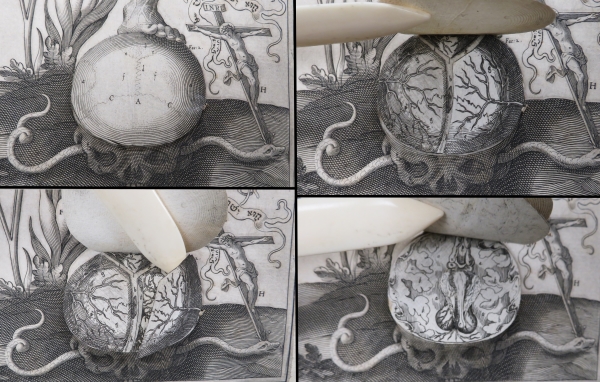

Plate 1 of Remmelin Catoptrum Microcosmicum (Ulm, 1639)

Remmelin seems to have designed his ‘survey of the microcosm’ as early as 1605. The book features a unique journey into the human body through paper-flaps. It follows the foundational work of Andreas Vesalius’s De Humani Corporis Fabrica and that of the many anatomical fugitive sheets which circulated in the sixteenth century. Anyone who has ever played with a 3D anatomical model understands that layering is a powerful educational tool in understanding the human body.

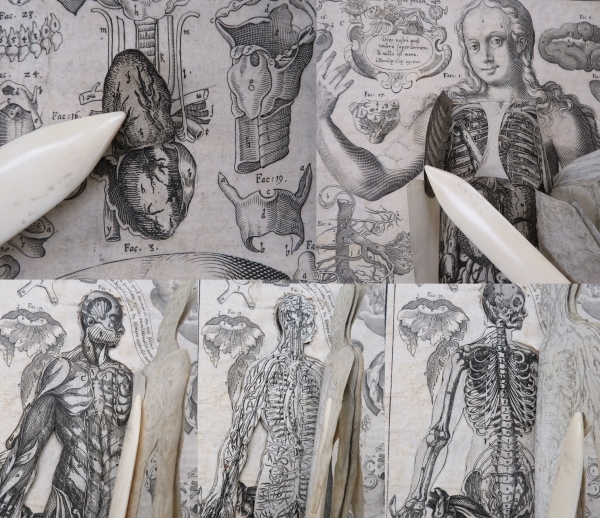

A later English edition delightfully describes this ‘little world’ as ‘an anatomie of the bodies of man and woman wherein the skin, veins, nerves, muscles, bones, sinews and ligaments are accurately delineated. And curiously pasted together, so as at first sight you may behold all the outward parts of man and woman. And by turning up the several dissections of the paper take a view of all their inwards’:

Remmelin reveals Adam and Eve’s most intimate anatomy in successive plates, where the reader, dissector or casual player can flip up to eight layers of nerves, bones, muscles and organs, including a rare anatomical view of the brain:

Lavish with biblical quotations and symbols, and containing a medical knowledge already outdated at the time of publication, Catoptrum microcosmicum looks like a memento mori. The volume is also famous because it was the subject of a long ownership dispute: in 1613 the publisher, a certain Michael Spacher, circulated the anatomical plates under his name, without key or text and without citing Remmelin or the skilful engraver, including only their initials. As this dispute has been summarised elsewhere, allow me to return to the Royal Society’s copy.

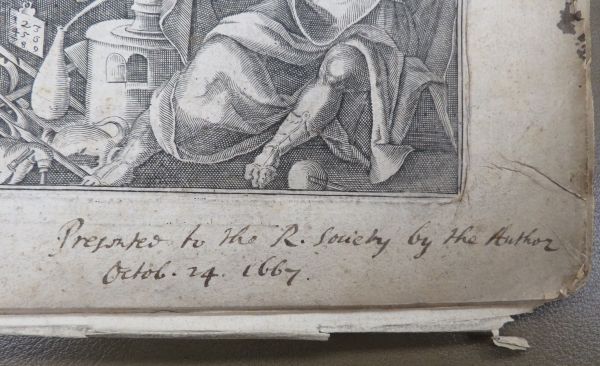

On the title-page is inscribed in the trusted hand of Henry Oldenburg: ‘Presented to the R. Society by the Author Octob. 24 1667’:

This would be a great starting point to establish provenance… if Johann Remmelin had not died in 1632! Could the term ‘author’ refer misleadingly to the anonymous Ulm publisher responsible for our 1639 edition? Could it be that these were the plates the London printer Joseph Moxon used to publish his 1670 edition of An exact survey of the microcosmus, translated into English by John Ireton, the former Lord Mayor of London? A much more prosaic answer comes from the Royal Society’s Journal Book entry for the meeting of 24 October 1667 – the copy was in fact donated by newly-elected Fellow John Collins, alongside various of Collins’s own books. It is therefore likely that Oldenburg inscribed everything donated by Collins that day with the same sentence, failing to notice that this volume was not in fact authored by the mathematician. Perhaps we should forgive Oldenburg, who was fresh out of the Tower of London!

Remmelin’s anatomical flaps would continue to be associated with the Royal Society later in the seventeenth century, when the poetically-named physician Clopton Havers (1657-1702) published a revised version of the Catoptrum microcosmicum in 1695, updated for medical practitioners. Lianne Habinek notes in her informative volume on early modern neuroscience, The subtle knot, that Havers’s corrected edition included the most-up-to-date brain imagery and symbolised the scientific impetus of the Royal Society.

In addition to being a fascinating and beautiful volume, Catoptrum microcosmicum is an excellent example of the pitfalls of provenance information, and a way to introduce you to some of the tools that can be used to study the origins of the Royal Society’s historical collections. By way of conclusion, and before anyone requests that we digitise our rare 1639 edition, I would invite you to read further on the type of conservation and technical challenges faced by such enterprises.