Read more about the story of a mummy that was once part of the Royal Society’s museum.

I recently visited the excellent Tutankhamun exhibition at the Saatchi Gallery in London. It’s an amazing collection of artefacts and objects from the Boy King’s tomb, all created to help him on his journey through the afterlife. The exhibition inspired me to do a bit of digging through our own archives, to unearth the story of a mummy that was once part of the Royal Society’s museum.

King Tutankhamun’s golden funerary mask, from Wikipedia (Creative Commons licence)

King Tutankhamun’s golden funerary mask, from Wikipedia (Creative Commons licence)

Regular readers of our blog may recall that Henry Howard, 6th Duke of Norfolk, donated an Egyptian mummy to the Society’s museum, or Repository. Nehemiah Grew described it in his 1681 Musaeum Regalis Societatis catalogue as ‘an entire one taken out of the Royal Pyramids. In length five feet and ½, defended with several linnen Covers, all woven like ordinary Flaxen Cloth’. We don’t know where the Duke got the mummy from, though trade in mummified remains from Egypt was common throughout Europe, and specimens often found their way into private hands for display, or were destined to be unwrapped and examined. Mummies were also ground up to make medicine, while mummy brown was a popular colour used by Pre-Raphaelite painters. You can probably guess what the main ingredient was…

The Royal Society might not seem the most obvious place to deposit a mummy, but it’s worth remembering that we were one of the few learned societies with an interest in antiquarian matters at the time. The College of Antiquaries had been shut down by King James I in the early seventeenth century, and its successor organisation, the Society of Antiquaries of London, wasn’t established until 1707. A number of early Royal Society Fellows were certainly avid antiquaries: John Aubrey and William Stukeley were both well-respected in the field, while Sir Hans Sloane’s enormous collection was bequeathed to the nation upon his death in 1753, becoming the British Museum.

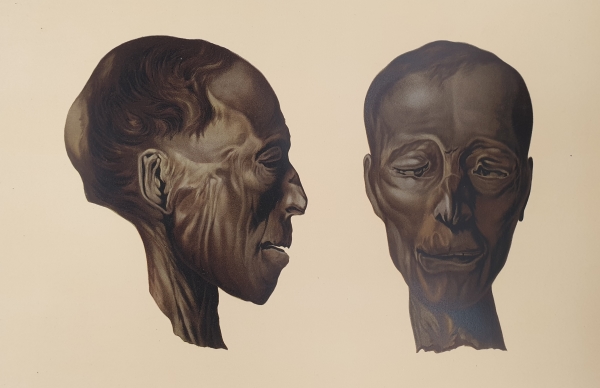

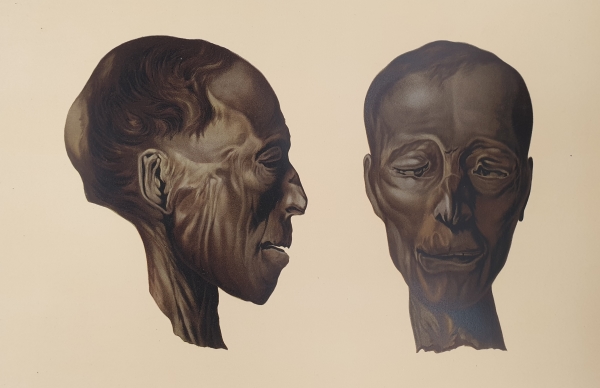

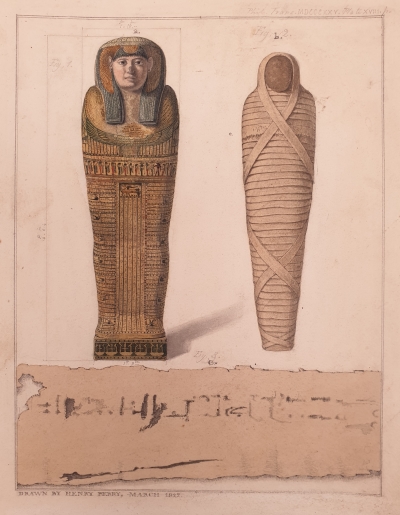

Profile and face of a male mummy, from a book plate for a late 19th century publication about Pharaonic Egypt (RS MS/827)

Sadly, the Repository was not always well cared for, and numerous artefacts were lost or damaged. Norfolk’s mummy was in poor condition by the 1730s, so in 1733 the Council of the Royal Society arranged for it to be cleaned and housed in a protective case. However, in 1734 a committee appointed to inspect the state of the museum collection reported that Norfolk’s mummy was falling to pieces, having been stored upright rather than laid flat.

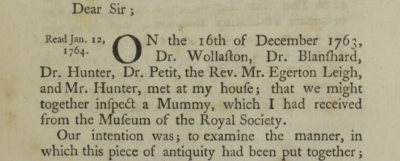

In December 1763 John Hadley FRS, a London doctor, borrowed the mummy from the Society on behalf of a group of physicians who planned to dissect it and study the embalming process. He wrote a report on their findings which was published in the Philosophical Transactions in 1764, making it one of the earliest printed accounts of the unwrapping of a mummy.

Extract from ‘An account of a Mummy, inspected at London 1763’ by John Hadley, in Philosophical Transactions Volume 54

In his report, Hadley began by noting the poor condition of the specimen. The wrappings were badly damaged and a number of bones were recorded as broken or missing. Worst of all, the outer layer of painted wrappings had been nailed to the torso, and the feet had been attached to the mummy’s case with wire. Comparing the sorry state of the body to Grew’s 1681 description, he concluded that the damage ‘had most probably been done by those, who had orders some years since to repair it … they seem to have done their work in a most clumsy manner’.

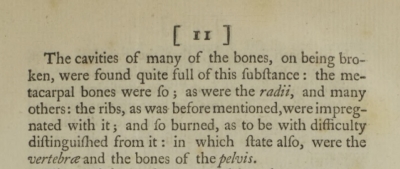

The dissection began with the removal of the linen wrappings, and Hadley remarked that each subsequent layer had been wrapped in a different direction to the one before. Once the torso was exposed, they had to break through the hardened layers of bandage and preservation oils in order to examine the skeleton underneath. The investigation was certainly undertaken carefully and scientifically, but it nevertheless caused further damage to the remains of Norfolk’s mummy. This included breaking bones to examine the medullary cavity inside.

Most of the soft flesh of the mummy was missing, and Hadley concluded this had been caused by the boiling of the body in hot oil. It was erroneously believed at the time that this was undertaken during embalming; in reality, Egyptian embalmers would dry the bodies in natron after removing the internal organs, and then apply oils and preserving agents throughout the process. The most likely explanation is that the poor state of the specimen exposed the flesh and caused it to decay. The wrappings on the feet remained intact, however, and a remarkably well-preserved root was still bound to the left foot, where it had been placed during the embalming process:

Drawing of the left foot of Norfolk’s Mummy, from Hadley’s account

It isn’t clear what happened to Norfolk’s mummy after Hadley’s group had completed their dissection. If it was returned to the Royal Society (we don’t hold any records confirming this), then it might have been transferred to the British Museum in 1781, along with the rest of the Repository collection. The left foot, complete with plant bulb, was separated from the rest of the remains at some stage, and still survives in the collection of the Royal College of Surgeons.

From ‘An essay on Egyptian mummies; with observations on the art of embalming among the ancient Egyptians’ by Augustus Bozzi Granville, published in Philosophical Transactions volume 115

Hadley didn’t expect his report to make any great contribution to the study of ancient Egyptian burial practices: ‘A greater number of authors have written on this subject, than I was aware of; so that, in all probability, we have not made any new discoveries’, was his slightly downbeat conclusion. However, his methodical approach to dissection and documentation was an important influence on later investigations undertaken in the nineteenth century. Italian physician Augustus Bozzi Granville FRS carried out what is widely recognised as the first full medical autopsy on an ancient Egyptian mummy. In his report in the Philosophical Transactions in 1825, he praised Hadley’s work, stating that it ‘contains a very clear statement of the successive operations for ascertaining the real condition of the mummy’. The story of Granville’s mummy is fascinating in its own right, but I think we’ll have to unravel that tale another time.