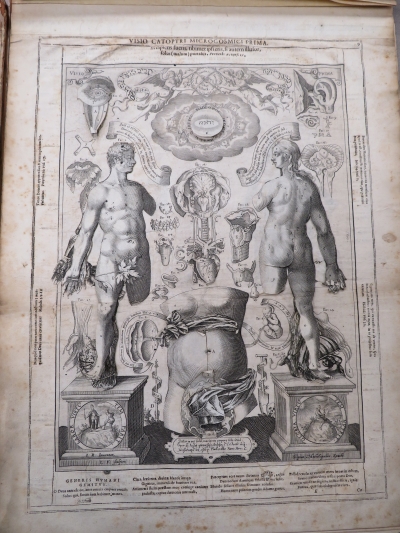

Read more about a donation made to the Royal Society by the family of one of the Society's founding members.

The first portraits were presented to the Royal Society in the 1680s, and since then our collection has grown to include over 300 pieces. Earlier this year we were lucky enough to receive a donation from a family whose ties to the Society date back to our foundation.

Abraham Hill (1633-1721) was a founding Fellow of the Royal Society. A merchant by trade, he also studied at Gresham College and was an avid book and coin collector. Though not generally remembered for his scientific genius, Hill’s administrative commitment made him a valued Fellow and the first to fill the role of Treasurer. In 1950, his portrait was offered to the Society on permanent loan by a descendant, Mrs Ursula Hill:

Portrait of Abraham Hill attributed to John Hayls, n.d. © The Royal Society (P/64)

Seventy years later, in January 2020, we heard from Ursula’s grandson, who offered us a portrait they believed to be of Abraham’s first wife Anne Hill (née Whitelocke) – an offer we welcomed with open arms:

Portrait of a woman, believed to be Anne Hill, n.d., attributed to John Hayls

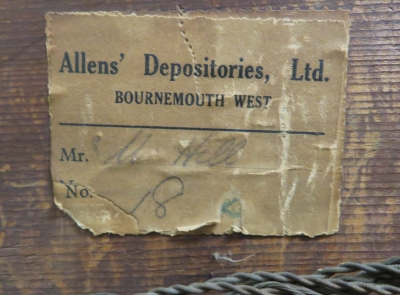

The portrait certainly seems to be a pair with that of Abraham. Though this woman’s frame is a little chunkier, the ‘by-site’ dimensions of their canvases are similar, and her backboard provides evidence that she travelled with the portrait of Abraham, as it has an identical label from a furniture removal company:

Label on the reverse of portrait of Anne Hill. ‘Allens’ Depositories, Ltd. BOURNEMOUTH WEST. Mrs U. Hill. No. 18’

The existence of a portrait of Abraham’s wife allows us to narrow the date window on our portrait of Abraham which, until recently, was listed as ‘seventeenth century’. Abraham was twice married. His first marriage, to Anne, lasted from 1656 until Anne’s death in 1661, while his second marriage, to Elizabeth Pratt, lasted from 1662 to 1672. In order to establish that our sitter was either Anne or Elizabeth, I first wanted to rule out the possibility that she was the wife of Abraham’s brother, Thomas Hill (1630?-1675).

I had become aware of a portrait of Thomas, now hanging in the Pepys Library, Magdalene College:

Thomas Hill by John Hayls, 1666 © Magdalene College, Cambridge; donated by Mrs Ursula Hill’s son, Major P. M. Hill, in 1945

What we know about Thomas Hill has largely come from the diary of former Royal Society President Samuel Pepys (1633-1703). Pepys speaks highly of Thomas on a number of occasions (‘So to the Coffee-house, and there very fine discourse with Mr. Hill the merchant, a pretty, gentile, young and sober man’), and the two often enjoyed a night of music and singing together. Also a merchant, Thomas was based in the West Country, though he spent extended periods in Italy, where he was sent by their father to learn the trade, and Lisbon, where he died in 1675.

In the introduction to a printed edition of The letter book of Thomas Hill, 1660-1661, editor June Palmer argues that Thomas never married. The untimely deaths of his mother and father in 1660 left Thomas, as their only son still living in Devon, preoccupied with settling their estates. This was a time-consuming task and prevented any immediate possibility of marriage. Certain of Thomas’s comments to friends in the letter book (‘The new hint of my getting married is in no ways true. God grant that there might be ladies young, rich, beautiful, but they cannot be found on the streets so easily’), and the fact that no wife is mentioned in his will, seem to support this notion.

Whether our sitter is Anne or Elizabeth Hill is less clear, though a strong argument seems possible for Anne. Firstly, the portraits of Abraham and his wife were passed down through Abraham’s children, Richard and Frances, whose mother was Anne rather than Elizabeth. Furthermore, there appears to have been a tradition within Anne’s family towards commissioning portraits. A couple of likenesses of her father Bulstrode Whitelocke, the well-known Cromwellian Ambassador to Sweden, survive, as does one of her mother Frances by Michael Dahl.

Bulstrode Whitelocke by an unknown artist, 1634 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Michael Dahl moved in the same circles as John Hayls (1600-1679), the painter to whom we currently attribute our portrait of Abraham. We know that Hayls is responsible for Thomas’s portrait. Again, we have Pepys’s diary to thank for this. On 14 February 1666, Pepys writes that ‘I took Mr. Hill to … his painter, Mr. Hales, who is drawing his picture, which will be mighty like him.’ Indeed, Pepys was so impressed that he had Hayls paint his wife, his father and himself, which led to Hayls’s best-known piece:

Samuel Pepys by John Hayls, 1666 © National Portrait Gallery, London

It’s very possible that Hayls’s interaction with the Hill family didn’t start or end with Thomas. The similarities between the painted depictions of the brothers are present in their matching dark robes, white neckties and the finish on their hair. Significantly, too, their frames are identical. We know from Pepys that Hayls supplied his own frames – ‘thence to Mr. Hales’s, and paid him for my picture, and Mr. Hill’s, for the first 14/. for the picture, and 25s. for the frame’ – so if we can prove that these are the originals, we’re closer to moving from artist attribution to confirmation than ever before.

Frame close-ups: left, our portrait of Abraham Hill in Carlton House Terrace; right: the portrait of Thomas Hill in Magdalene College, Cambridge

I sought the opinion of the Royal Society’s frame restorer on this. He believes the frames of Abraham and of his wife date to the late seventeenth century, citing as evidence the fact that they are carved: composite, mass-produced frames replaced most carved frames in the eighteenth century. He also explained that artists such as Peter Lely and Anthony van Dyck introduced the trend of designing their own frames in the seventeenth century, as it allowed them to be more creative and express movement in their framing, so it’s not out of the question that Hayls, who was a known imitator of Lely, designed his own frame.

Hayls’s portraits of men seem to favour their sitters’ straining their neck to look out at the viewer (other examples can be found here and here), and when we look at another female sitter…

Portrait of a Lady, said to be the Countess of Loudoun, by John Hayls, n.d. © The Great Steward of Scotland’s Dumfries House Trust

… we see a similarity in posture, while the treatment of the drapery, and details such as the neckline, choice of jewellery and the curls around the face, are almost identical. Furthermore, though the frame of our female sitter appears different to that of Abraham’s and Thomas’s on first glance, our framer noted that the shot bead and waterleaves from the latter two appear alongside the floral carvings in hers. In other words, there’s a common pattern uniting all three frames.

Though we cannot know for sure, there’s a strong sense that Hayls is at work somewhere in the painting and framing of these portraits of Abraham and his wife. As for our female sitter, it’s possible I’ve raised more questions than answers in this research (but is that a hint of Bulstrode Whitelocke I detect around her eyes…?) More Hill family papers, including eleven of Abraham’s commonplace books, are distributed between the British Museum and the British Library. I hope to have the chance to sift through these for clues in future, possibly settling this mystery once and for all.