Archivist Virginia Mills looks in on the Red Lion Club, founded in 1839 by Edward Forbes FRS as a protest against the ‘Dons and Donnishness of science’.

For as long as there have been learned societies there have been banquets, dinners and dining clubs for the members. They provide a more social and informal forum for exchanging views, on the principle that intellectual stimulation is improved by satisfying the demands of the body in the form of copious food and drink.

The Royal Society is no exception, with early Fellows meeting in coffee houses and taverns. From 1743 – possibly earlier – a subset of Fellows chaired by the President met to dine and hear speakers at the Royal Society Club, also known as ‘Thursday’s Club’ after the day of the Society’s weekly meeting. A parallel dining club, the Philosophical Club, begun in 1847 as a group seeking reform within the Fellowship. The two later merged, and there continues to be a Royal Society Club to this day.

There is also the example of the influential X-Club, an exclusive group of nine respected Victorian scientists who were champions of Darwin’s revolutionary theories. The members, among them Joseph Hooker PRS, John Tyndall and John Lubbock, dominated the administration of the Royal Society and many other learned societies, particularly from 1865 to 1880, exerting enormous influence over the direction of scientific study and the dissemination of information. They were united by similar ideals for academic liberalism and the professionalisation of science.

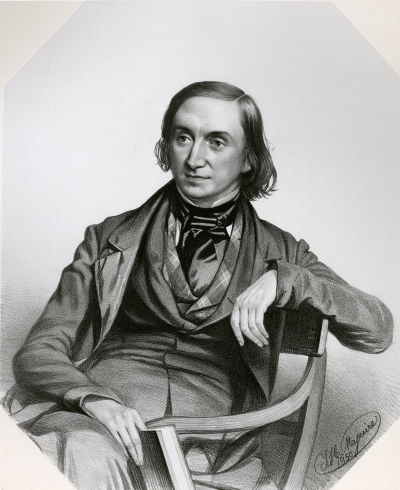

Edward Forbes FRS (1815-1854), founder and ‘Lion King’ of the Red Lion Club, by J H Maguire, 1850 (RS IM/001489)

At the other end of the scale is the Red Lion Club. In the words of one of its members Thomas Huxley (also ironically a member of the X-Club), this was set up as a protest against the ‘Dons and Donnishness of science’, and its dinners were deliberately of ‘spartan simplicity and anarchic constitution’. The founder of this irreverent feast was naturalist Edward Forbes FRS, who held the first gathering at the Red Lion Inn, Birmingham, during the 1839 annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, in order to ‘counterblast the official Banquets of the Association’ which he found dull and conventional.

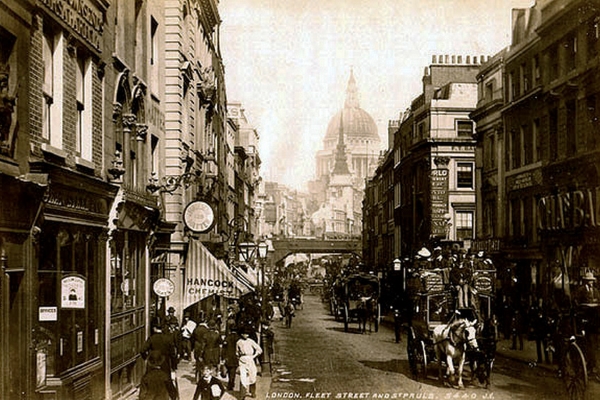

Fleet Street by James Valentine c.1890 (Wikimedia Commons)

Forbes appointed himself the Lion King and his fellow scientist-diners as cubs, and the pride continued to meet during the annual Association meetings until the beginning of the twentieth century, After Forbes became Chair of Botany at King’s College in 1842 there was an active metropolitan branch of the club in London. They met in Fleet Street (known colloquially in the nineteenth century as ‘tippling street’), sometimes at the famous old institution the Cheshire Cheese, still a quality boozer to this day, and sometimes at the old Anderton’s Hotel, proprietor Frederick Clemow.

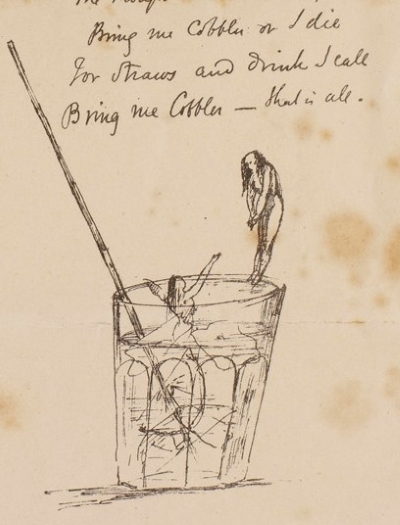

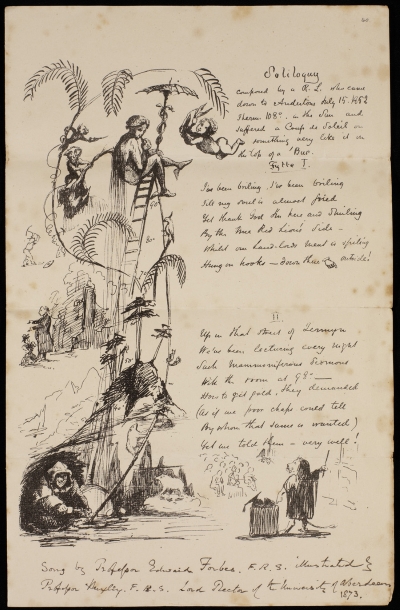

Forbes, evidently multitalented, fancied himself a bard as well as a scientist, and at every meeting of the Red Lion Club would chant at least one new satirical poem. Several examples of these poems, which Forbes referred to as ‘songs’, have found their way into the Royal Society archive amongst the papers of other members of the club. I’m featuring one entitled Soliloquy, found in the correspondence of Sir Henry James, Knight Director General of the Ordnance Survey, and originally written around 1852; ours is a later copy of the poem, illustrated by fellow lion cub Thomas Huxley in 1873:

Soliloquy: song by Edward Forbes FRS, illustrated by Thomas Huxley FRS, 1873 (RS MS/744/1/40)

In order to get the proper effect you should probably read the verses aloud in the style of Forbes, which his biographers described as ‘chauntering’ in a ‘species of recitative that rendered them highly amusing’. Also bear in mind that the club members would meanwhile be expressing their approval in the accepted manner, with lion-like roars and flapping tailcoats. As one of many who has recently watch Netflix’s Tiger King, I can’t help but wonder at the apparently enduring fascination big cats seem to hold for eccentrics! Anyway, here’s my transcription of part of Soliloquy:

I’ve been boiling, I’ve been boiling

Till my soul is almost fried

Yet thank God I’m here and smiling

By the true Red Lion’s side –

Whilst our land-lords meat is spiling

Hung on hooks – down there outside!

Up on that street of Jermyn

We’ve been lecturing every night

Such mammoniferous sermons

With the room at 98° –

How to get gold, they demanded

(as if we poor chaps could tell

By whom the same is wanted)

Yet we told them – very well!

If they find it – if they find it

Of course we shewed them how & where

The quartz we bade them grind it

Methinks I see them now

With the sweat upon their brow

Grubbing down there in the lodes

Of the distant Antipodes

And if Diamond-jolly jewel

Should in the diggings shine

Of the palaeozoical fuel

I will claim a share as mine

By Gum!

But that’s ruum!

Don’t I wish that I may get it

Well – I’m very happy here

As long’s my muzzle’s wetted

With Mr Clemow’s beer.

Yet is there consolation

Though boiled like roasted skate

Mild is my situation

To our colleague Ramsay’s fate

Doomed to the marriage halter

When the Mercury’s so high

The thought it makes me falter

Bring me cobbler or I die

For straws and drink I call

Bring me cobbler – that is all.

Forbes’s chief concern on this occasion seems to have been giving his lectures during uncomfortably hot weather. Huxley’s accompanying illustrations depict him as a lion in cap and gown, but he is not above some bawdy lampooning of his colleagues: pity poor Andrew Crombie Ramsay, whose performance as a newlywed was called into question on account of the heat wave. The date of Ramsay’s marriage in 1852, by the way, was a great help in determining the date of the original poem.

Clearly Forbes sought to be comedically irreverent to all forms of establishment, from science education to marriage. The irony – not lost on Forbes, I’m sure – is that he was a member of the scientific establishment he lampooned: elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1845, he became president of the Geological Society of London eight years later. This does seem an unlikely position for the author of A doleful ballad about the red tape worm, in which he laments the burden of bureaucracy. In taking aim at the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Benjamin Disraeli, Forbes also strayed from vulgar to antisemitic; while not likely to attract censorship at the time, this particular Soliloquy verse doesn’t need to be transcribed again for the purpose of this blog.

Huxley’s illustration of Fleet Street for Forbes’s Soliloquy (RS MS/744/1/40)

There is a definite element of self-mockery in Soliloquy. Forbes laments the lack of money to be made in science, chastising his geology students who wish to learn how to get rich from their teacher, even as he promises to take a cut if they strike gold or ‘jolly diamonds’. Huxley illustrates this with a carriage of fine gentlemen travelling past Anderton’s Hotel down Fleet Street, going ‘all the way to the Bank’ with an old lion trotting behind them.

As a young man Forbes himself originally began training as an artist, but found art intellectually unsatisfying (while keeping up a bit of caricature on the side) and switched to studying medicine at Edinburgh, the only option available for formal scientific education that would lead to potentially profitable employment. One of Forbes’s obituaries records that he was inattentive to the purely medical lessons and was only interested in botany and natural history lectures. He ultimately gave up his medical studies too, and made a career as a professional naturalist, travelling with expeditions and later taking a curatorial position at the Geological Society.

Forbes published monographs and papers in numerous respected scientific publications, but seems to have remained a tearaway at heart. Rarely in the dissecting room or infirmary during his Edinburgh days, he was more likely to be found in the thick of a student snowball fight, including the infamous ‘snowball riot’ of 1838, which had to be broken up by the military brandishing bayonets! He subsequently wrote a poem about it, of course.

For those who want yet more of his literary stylings, other Forbesian titles in the Royal Society archive include The Anatomy of an Oyster and Valentine by a Palaeontologist. Come and take a look when we are open again; in the meantime, to get through times of stress, do as Forbes did and enjoy a nice cobbler – a shaken cocktail with crushed ice and fruit, and very refreshing. ‘Bring me cobbler – that is all’!