To coincide with the launch of the Notes and Records Essay Award 2021, we spoke to Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira, the winner of the 2019 prize.

The Notes and Records Essay Award 2021 has now been announced, we decided to go back to the 2019 winner, Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira, and find out more about his winning entry.

Would you explain how French attitudes towards ballooning changed before and after the 1870-1 Franco Prussian War?

The French had a complicated relationship with ballooning throughout the nineteenth century. On the one hand, they expressed pride in being able to claim that it was a “French invention,” since the Montgolfier brothers made the first registered public balloon demonstrations in 1783. On the other hand, there was a lot of frustration from the fact that the technology did not seem all that useful. At first people enthusiastically expected that developing ways to steer balloons would revolutionize the world, fundamentally transforming the political and economic spheres. But obviously that did not materialize, and by the early nineteenth century there was widespread disillusionment, with most authorities and men of science giving up on ballooning, which then became the province of entertainers and utopian thinkers who tended to live on the margins of society.

Things started changing in the 1860s, when a more concerted effort in using the balloon as a meteorological technology coalesced. Men like James Glaisher in England (the subject of Amazon’s recent The Aeronauts movie, which I’ve written about elsewhere), and Camille Flammarion, Gaston Tissandier, and Wilfrid de Fonvielle in France developed a lose network that shared data collected from higher altitudes through balloon ascents. In 1870 they published the wonderful Voyages aériens, with an English translation appearing the following year.

Although the aeronautical community in France was already acquiring some momentum before the war, the Siege of Paris had a major effect. Surrounded by the Prussians and isolated from the rest of France, Parisian authorities had to find a way to communicate with the outside world, especially since so much was centralized in Paris because of how state institutions developed after the French Revolution. Furthermore, communication was key in maintaining morale during the four-month-long siege. And the balloon seemed to offer the perfect solution. Parisians turned their train stations into balloon manufactures, and more than sixty departed from Paris carrying official dispatches, private letters, scientific equipment and Léon Gambetta, who was the Government of National Defense’s Minister of War and Minister of Interior (and, if I am not mistaken, the first active politician to travel by air).

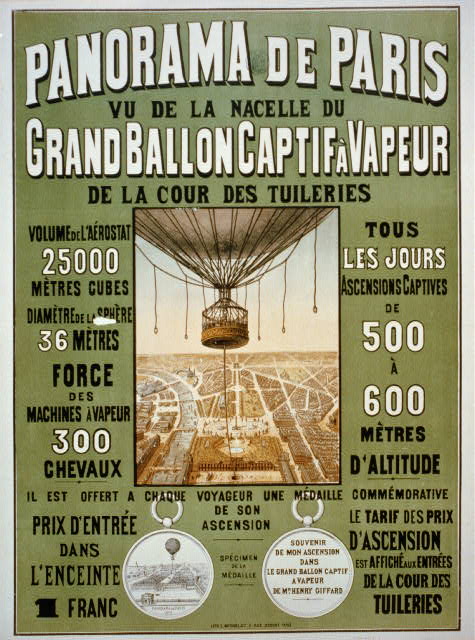

Figure 1: Puvis de Chavannes’s Le Ballon, painted during the Siege of Paris and getting at this idea of the balloon as an emotive technology.

Now, the siege balloons were not a panacea, and communications continued to be an issue—getting news back to Paris was especially challenging. And because they were not steerable, they were unreliable, with one even ending up in Norway! Regardless, it was a very visible technology in the war effort, and one that the French sympathized with. Since the whole war was a catastrophe, it ended up being interpreted as one of its redeeming heroic efforts. All of this meant that by the end of the war the balloon had become a kind of emotional technology, with the status of ballooning being much different than what it was just a decade ago, when it was usually seen as a trivial form of entertainment. Aeronautical societies after the war, like the Société Française de Navigation Aérienne (the Zénith ascent’s organizer), had much more credibility and public support than the ones from before the war.

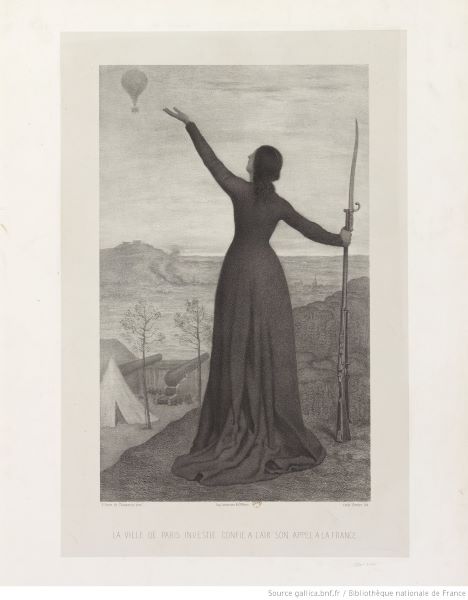

Figure 2: Henri Giffard’s ballon captif for the 1878 Exposition Universelle advertisement.

How did the balloon Zénith’s 1875 high-altitude ascent that killed two aeronauts—Joseph Crocé-Spinelli and Théodore Sivel make these two aeronauts scientific martyrs?

This goes back to the Franco-Prussian War question. As I mentioned above, ballooning was seen as one of the few redeeming elements of the French war effort, so it had already acquired a more heroic dimension. At the same time, one of the narratives the French developed to explain their defeat was that Prussia had leaped past France in scientific and technological matters. This was expressed in a witticism attributed to Louis Blanc at the time: “The Prussians are like Mohicans who graduated from the École Polytechnique” (a witticism that also expresses racism, of course). So, the republicans who worked toward consolidating their new regime after the war saw science and technology as central to both internal nation-building and international stature. This fits within a broader nineteenth-century phenomenon as well, for with the rise of nationalism we start seeing a more concerted effort at commemorating scientific heroes as symbols of the nation (Christine MacLeod has done great work on this in the British context). With Crocé-Spinelli and Sivel specifically, there are a few components that I think help explain why they became, as far as I know, the Third Republic’s first scientific martyrs: first, they were themselves committed republicans, and had connections to leading republican figures like Gambetta and Paul Bert (who wrote a foundational tome on atmospheric pressure and went on to serve as Minister of Education); second, they were engaged in a practice (ballooning) whose prestige had elevated significantly in the past few years; third, the way they died (high-altitude anoxia) offered an ideal scenario to combine religious and spiritual narratives, as we see expressed in the poems people wrote about the tragedy (something I discuss towards the end of the article).

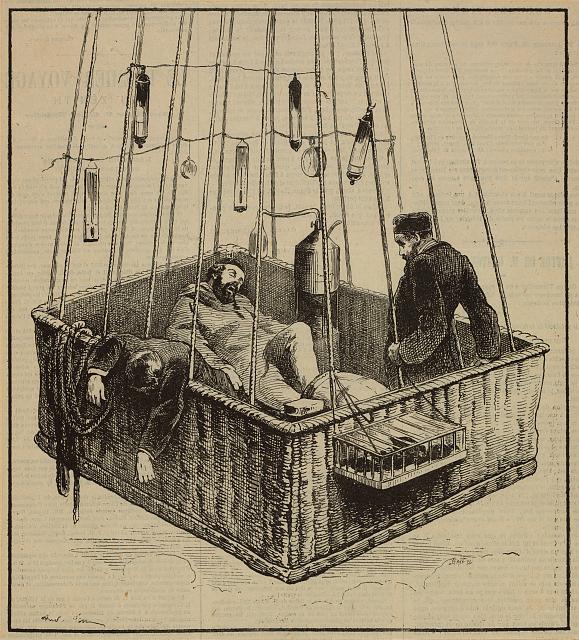

Figure 3: Wood engraving depicting the Zénith basket during the tragic ascent

What inspired you to do this particular essay? What surprised you the most in your research process?

The essay stems from a chapter in my dissertation, “The Ascending Republic: Aeronautical Culture in France, 1860-1914,” which I am currently transforming into a book manuscript. I first got interested in the Zénith ascent as I was browsing through the contemporary press, and I was surprised by just how widely covered it was—both the preparations for the ascent and the subsequent tragedy. But what really prompted me to examine it from the martyrdom perspective was a visit to the Père Lachaise cemetery, where Crocé-Spinelli and Sivel are buried underneath a monument commemorating their sacrifice. It is in a quieter part of the cemetery, somewhat off the tourist path, and it was a touching experience. The bronze sculpture presents a kind of idealized naturalism that drinks from the Romantic tradition. It depicts the two aeronauts holding each other’s hand and draped with death cloths. When I visited, the pathos it evoked was compounded by there being a withered bouquet between their heads. It was January, so someone probably placed it there in the previous Fall, perhaps during the Toussaint (All Saints’ Day). I found it both moving and fascinating that someone had chosen to honor these figures that are now pretty much unknown. But I soon returned to a more analytical mindset, for I noticed that a few steps down the alley there was a monument honoring the soldiers who had died during the Franco-Prussian War. That was when things began to click together, and the connections between the death of these scientists and the trauma of France’s 1870-1 defeat started to become obvious.

I would say that what surprised me the most was coming across all the poems celebrating the aeronauts’ sacrifice that people mailed Gaston Tissandier (the ascent’s sole survivor). Most of these show little signs that the writer had much knowledge about the kind of science the aeronauts were pursuing, which just goes to show the symbolic power of the enterprise. The one I discuss in most detail is “Le Zénith,” an 1876 poem by Sully Prudhomme, who would go on to win the first Nobel Prize for Literature in 1901. But just as fascinating are the poems (published and unpublished) written by students, amateur poets, etc.

Something else that I found very interesting (but which did not make it into this article) was how these aeronauts went about in collecting data for early atmospheric science. They would triangulate the measurements that they collected from the balloon with sheets that they tossed to the ground, hoping that people would come across them and fill them up with information regarding temperature, wind direction, cloud coverage, etc. People would then take these to the local mayor or teacher and send them back to the Société Française de Navigation Aérienne. This means that men of science, the state, and those that might be considered to be in more marginalized positions worked together in complex ways to create scientific knowledge. I even found a sheet that was stumbled upon by a local beggar! I cannot help but imagine the types of conversations these moments of scientific mediation engendered…

Figure 4: Tomb of Croce-Spinelli and Sivel (French scientists), killed in the crash of the balloon Zenith, 15 Apr. 1875

Have you ever been up in a balloon? Was your decision and your experience influenced by your research?

I have never been up in an untethered balloon. It is somewhat expensive, so if there are any generous souls who want to take me up on an ascent, I am all in (I will even throw in a high-altitude seminar)! I did go up on the tethered Ballon Generali at the Parc André-Citroën in Paris. It was fun, although the height it reaches (150 meters) does not do much in terms of offering the passenger a great view of central Paris… But it was curious how little the system had changed since Henri Giffard first developed it for the balloon that became the centerpiece of the 1867 and 1878 Expositions Universelles. I have actually been toying around with a piece on how you can trace the Eiffel Tower’s genealogy back to these balloons, and I think there might be something interesting to say about the “view from above” and the transition between the balloons’ ethereality to the tower’s concreteness.

Do you have any final thoughts on how technology can be bound up with patriotic objectives?

This is a field that has provided rich material for historians of technology and of nationalism, and the two continue to be tightly bound together in the present. There is a chauvinistic dimension to this rhetoric, especially when it comes to claims over who did what first. We see this in debates about who was the first in flight (for many Americans, the Wright Brothers; for many Brazilians, Santos-Dumont; for many French, Clément Ader). It was certainly very prominent during the Cold War’s “Space Race.”

What I find even more intriguing, though, is how science and technology allows for the insertion of patriotic discourse within an internationalist framework. Ballooning was definitely infused with patriotism after the Franco-Prussian War, but this patriotic practice played an important role in the transnational development of meteorology. The French, in fact, have been quite adept at situating themselves at the center of international organizations and exerting a kind of “soft power.” We see this in aeronautics, with organizations like the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale, and in chemistry, with how French chemists played a central role in nomenclature reform. Belgium is another country where the forces of patriotism and internationalism operate in often productive ways, as Robert Fox traced in Science without Frontiers (2016).

Unfortunately, the current moment, at least in the United States (where I am currently based), seems to be more inclined toward chauvinistic forms of technological competition. This is the impression I get from the bellicose rhetoric of Donald Trump’s “Space Force,” which one can see as a direct afront to the more internationalist approach expressed by initiatives like the ISS. We need to keep in mind that the rhetoric of patriotism can work in different ways depending on the context—the patriotism expressed during the Olympics is not the same as the one expressed during a war. As long as the nation-state continues to be the main geopolitical form of political representation, we should aspire to mobilize those patriotic passions in more productive directions that encourage exchange and collaboration rather than competition and isolation.

Notes and Records is an international journal which publishes original research in the history of science, technology and medicine. Find out more information about submitting to Notes and Records.

Figure Captions:

Figure 1: Puvis de Chavannes’s Le Ballon, painted during the Siege of Paris and getting at this idea of the balloon as an emotive technology.

Figure 2: Henri Giffard’s ballon captif for the 1878 Exposition Universelle advertisement.

Figure 3: Wood engraving depicting the Zénith basket during the tragic ascent

Figure 4: Tomb of Croce-Spinelli and Sivel (French scientists), killed in the crash of the balloon Zenith, 15 Apr. 1875

Image of the blog author: Patrick Luiz Sullivan De Oliveira