A longitudinal study following life after lockdown in Wuhan, China, yields evidence of optimistic, albeit slow, improvement in well-being and mental health within the first 2 months after the 76-day lockdown restrictions were lifted.

On January 23rd, 2020, after Wuhan, China was identified as the epicenter of the novel coronavirus disease, the whole city went under lockdown with the most severe restrictions. All public transportation was cancelled, and no one was allowed to leave their homes without permission from authorities. During this time, all residents’ movements were highly monitored to identify households that purchased cold medicines, and only one member per household was allowed to go out for grocery shopping. According to the Xinhuanet, the biggest media organization in China, by the end of the lockdown, 50,340 COVID-19 cases were confirmed in Wuhan, of which 3,869 died.

On April 8th, the Chinese government ended the lockdown in Wuhan and gradually allowed residents to travel outside of the city limits and go back to work. It has been a concern whether economic recession and the negative effects that lockdown restrictions had on mental health might continue to prevent life to return to normalcy after lockdown was lifted. Further, even though the reduction of cases suggests that the city appears to have brought the outbreak under control, many people are still anxious about the second wave of infections in absence of a vaccine and about the risks of contracting the virus through asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. To understand the psychological experiences of those in Wuhan after lockdown was lifted, the day prior to lockdown ending, we recruited more than 300 adults residing in the city of Wuhan through the WeChat app – a popular social media app widely used in China.

ended the lockdown in Wuhan and gradually allowed residents to travel outside of the city limits and go back to work. It has been a concern whether economic recession and the negative effects that lockdown restrictions had on mental health might continue to prevent life to return to normalcy after lockdown was lifted. Further, even though the reduction of cases suggests that the city appears to have brought the outbreak under control, many people are still anxious about the second wave of infections in absence of a vaccine and about the risks of contracting the virus through asymptomatic COVID-19 carriers. To understand the psychological experiences of those in Wuhan after lockdown was lifted, the day prior to lockdown ending, we recruited more than 300 adults residing in the city of Wuhan through the WeChat app – a popular social media app widely used in China.

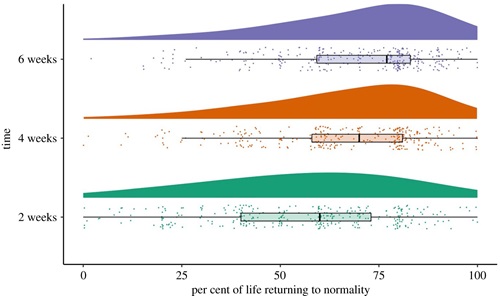

The findings of our study, which published last week in Royal Society Open Science, showed slow improvements in well-being and mental health after lockdown was lifted. Some of those changes make intuitive sense to us. For example, while motivation for self-isolating remains high in this sample, motivation appears to be driven more by individuals’ seeing the health benefits in self-isolating rather than fearing consequences from the government. Nonetheless, over the first 2 months, we see that people become less and less motivated to self-isolate at home. At the same time, we observe that our participants increasingly see their life as returning to normalcy; by the end of the first 2 months after lockdown was lifted, when asked how much of their life has returned to normalcy, participants estimated that about 75% of pre-pandemic life has been recovered.

Graph illustrating the rate of life returning to normality within the first two months after lockdown.

For mental health, to our surprise, we did not observe a drop in well-being nor a rise in mental health risks in our participants after lockdown was lifted. Our study suggested a slight improvement in those measures over time. We compared these results with two other longitudinal data sets in the United States and the United Kingdom with representative samples, and saw consistent evidence showing encouraging signs of psychological resilience throughout the pandemic.

However, because we used WeChat App as a recruiting tool, it could be the case that our sample represents a certain group of residents in Wuhan who are familiar with social media, and may use this app to reach out to their community for support during the lockdown, such as to seek social support and get help with everyday activities. Indeed, our results show that the more people engage in active problem-solving and help-seeking during lockdown, the lower mental health risks they display by the end of lockdown. Disruptions in continuing with everyday activities remain the most common source of stress for the participants in our sample, whereas financial stress or health anxiety did not matter as much. This is different from what we predicted, based on a previous registered report in Royal Society Open Science that showed health anxiety to be the main stressor at the beginning of lockdown in the UK.

As the COVID-19 pandemic continues, researchers and world citizens alike will continue to be uncertain about what our life will become after more countries lift lockdown restrictions. As such, we think it is important to conduct further longitudinal studies to get a more complete picture of people’s psychological experiences during and after lockdown. For now, our data suggested that there is a slow improvement of well-being and mental health after lockdown was lifted in Wuhan, and psychological outcomes appear to be more positive overall for those who engage in active problem solving, who are able to seek help and support, and who experience less disruptions in their daily routines.

This research was led by 1st year PhD student Tong Zhou at East China Normal University in collaboration with Dr. Thuy-vy Nguyen at University of Durham. This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities to Dr. Junsheng Liu at East China Normal University.

Royal Society Open Science is seeking submissions of Registered Reports relevant to any aspect of COVID-19 from any field. Find out more about the submission process for Registered Reports on the Journal page.

Images:

1. The first day of a kindergarten in Wuhan after lockdown was lifted (image kindly provided by study participant.)

2. Public park after lockdown in Wuhan (image kindly provided by study participant.)

3. Graph illustrating the rate of life returning to normality within the first two months after lockdown. Figure 2 from Zhou et al. A COVID-19 descriptive study of life after lockdown in Wuhan, China. 2020. Royal Society Open Science