Frankie Chappell presents our new Black History Month exhibit on Google Arts & Culture, highlighting stories from the Royal Society’s collections which feature the role of people of African and African-Caribbean descent in the history of science.

This week we’re proud to launch our Black History Month exhibit, A Celebration of Black Science, on Google Arts & Culture. Our aim was to unearth as many stories as we could from the Royal Society’s collections about the involvement of people of African and African-Caribbean descent in the history of science.

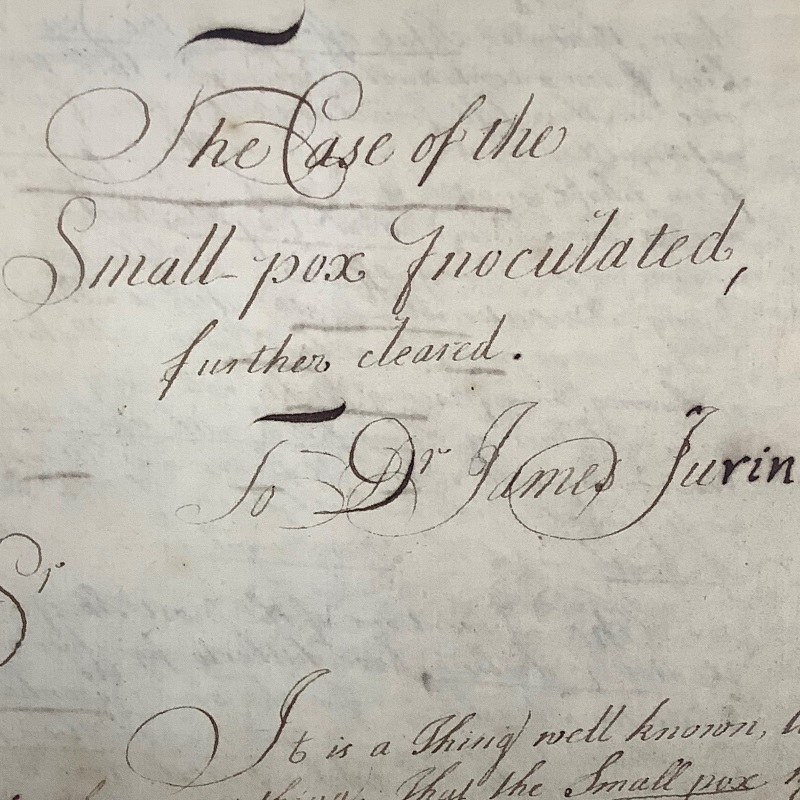

Some of the stories may be familiar: Francis Williams, John Edmonstone and the Sleeping Sickness Commission have all featured on our website or on the pages of our fellow London institutions. Despite the limitations of the pandemic, with restricted access to even our own archive, we’ve managed to identify a few new examples. The Society’s online journal archive was a great help with, for instance, all of the Philosophical Transactions issues digitised right back to the seventeenth century. We picked the brains of the Library team and other colleagues for leads, and were able to dig up a number of stories with relevant archival material, and in some cases detailed illustrations.

Once we’d identified the main stories, then came the issue of how to curate them into a coherent narrative. The digital exhibit comprises four sections: ‘Practices of Extraction and Cooperation’, ‘Exceptional Individuals’, ‘Women Healers’, and ‘Professionals in Colonial and Tropical Medicine’. The practices of medicine and healing seem to have been one particular area in which Black people could be recognised to some extent in the early material, and this theme links a number of the elements together across time and space.

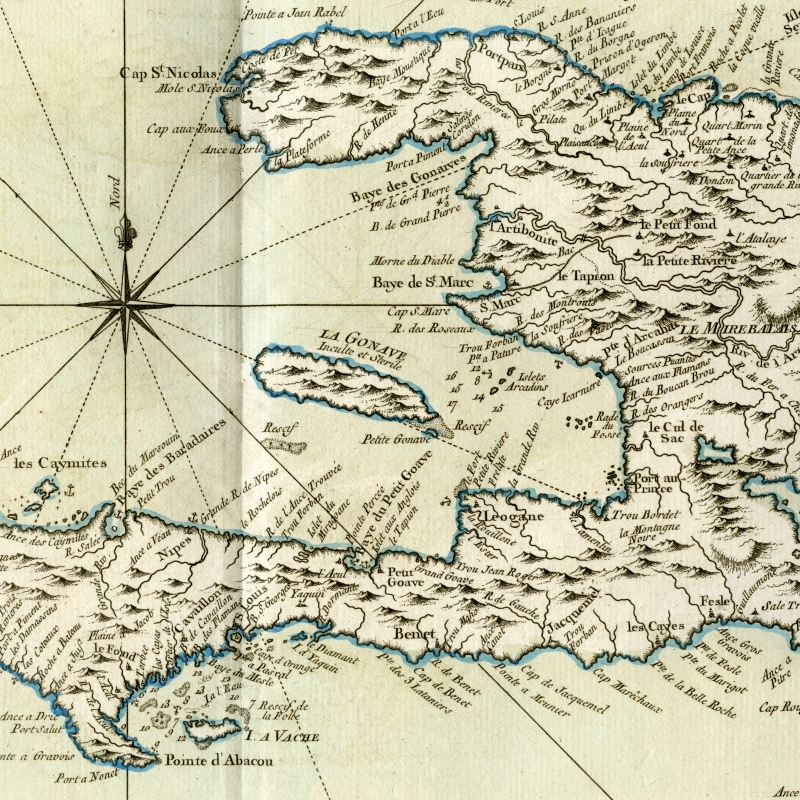

As Keith Moore showed in last week’s blog, the Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture himself had remarkable medical knowledge – a useful skill for a soldier and general. This also became a key avenue to ensure that Black women were represented in the exhibit, as women were even more difficult to identify in the history of science material.

Portrait of Joanna, by William Blake, 1796 © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

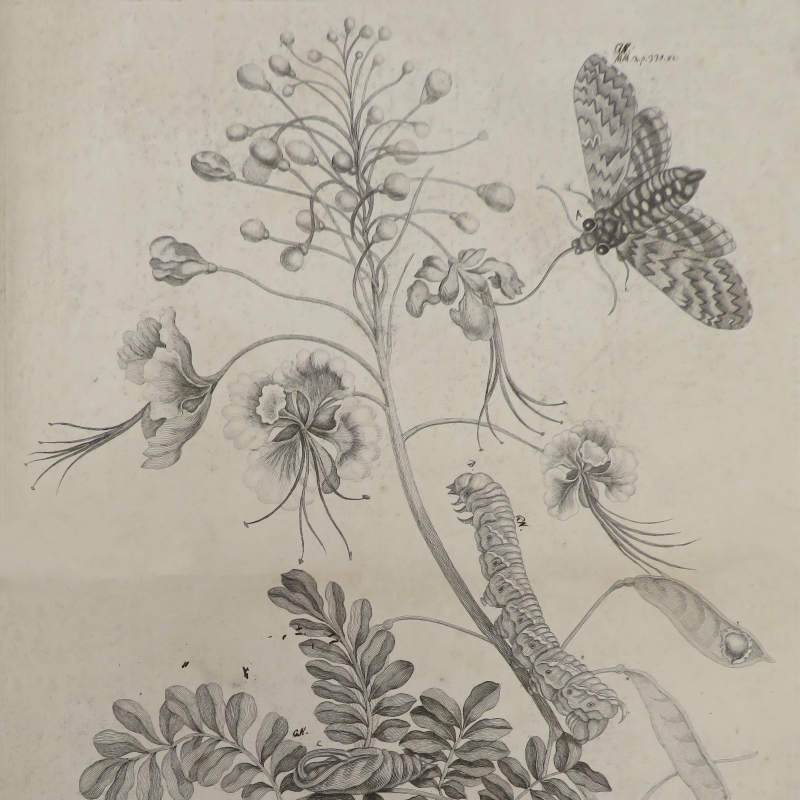

We discovered Joanna in William Blake’s illustrations for John Gabriel Stedman’s work Narrative of a five years expedition against the revolted negroes of Surinam while looking for an illustration of Kwasi in the same text. On that note, the under-studied nature of some of the individuals meant that finding images, or obtaining the rights to the images, was frequently a long-winded process.

The overarching narrative of the exhibit is the agency and contributions of Black individuals throughout the Royal Society’s history. However, it’s important not to gloss over the power structures and colonial contexts within which they operated. The first section of the exhibit covers some of this context, exploring how material in the archive drew on information, sometimes freely given, sometimes forcibly taken, from indigenous, enslaved and formerly enslaved people. Another theme of the exhibit became, who has been remembered in the historical record, and why? We rely on the archive to speak for these individuals, but when we are able to find Black people in the record, it is sometimes due to their connections to European men or to a colonial agenda. Kwasi, for example, seems to have been loyal to the Dutch forces and to have acted against rebel Maroon communities. John Edmonstone may not have been recovered from the record were it not for his contribution to Darwin’s discoveries.

Portrait of Kwasi ('The celebrated Graman Quacy'), by William Blake, 1796 © The Trustees of the Natural History Museum, London

These connections shape who is selected to be remembered, and how they are drawn in the annals of history. Scholars have argued that Joanna can hardly be faithfully reconstructed from Stedman’s rendering of her. As Saidiya Hartmann writes about an anonymous enslaved woman, the archive can become ‘a death sentence, a tomb … an asterisk in the grand narrative of history.’ The hope behind exhibits such as ours is that while the violence done by colonialism, and re-enacted by the archive, cannot be undone and should be interrogated, these neglected stories can disrupt the current prevalent, incomplete narrative of the history of science.

Furthermore, in that vein it’s important to research and celebrate figures whose attainments have not been acknowledged, and those who are not so easily commemorated in an exhibit, and therefore our aim is also to cast light into the shadows, gaps and silenced voices. As is highlighted in the Kwasi story, for the small number of individuals we can identify, there will be countless more who will go unrecognised. While Kwasi’s story is framed around one knowledgeable man, loyal to the colonial powers, in reality the information he shared will have been derived from the collective knowledge of the numerous Black and indigenous healers of Suriname.

We hope that this exhibit helps to spread awareness of these narratives and can contribute to more work on Black history within the history of science. If you have further information on any aspects of the exhibit, or more examples from within the Royal Society’s history, please do let us know. Happy Black History Month!