Katherine Marshall is impressed by the work of female paleoartists, including Ethel Seeley and sisters Gertrude and Alice Woodward.

While cataloguing some images of pterosaurs for the Picture Library database, I was intrigued to discover that the illustrations were by the author’s daughter. My subsequent research into paleoart by women illustrators led me to an artist working just a short walk from my childhood home. It’s a small world!

With the aid of a Government grant administered by the Royal Society, Harry Govier Seeley FRS was able to complete his research into winged reptiles by viewing specimens from all over Europe. This, along with ten years’ research gathering fossils from coprolite beds near Cambridge, resulted in the published work Dragons of the air: an account of extinct flying reptiles (1901).

This book, originally presented as a lecture series at the Royal Institution, contains 80 illustrations, with Seeley’s preface noting that ‘the drawings given in illustration of the text have been made for me by Miss E. B. Seeley.’ Delighted to see a woman’s contribution to science, I was keen to learn more. I revived my online genealogy account (a short-lived lockdown hobby), and the 1901 census confirmed my assumption that she was the author’s daughter, Ethel Brynhilda Jane Seeley.

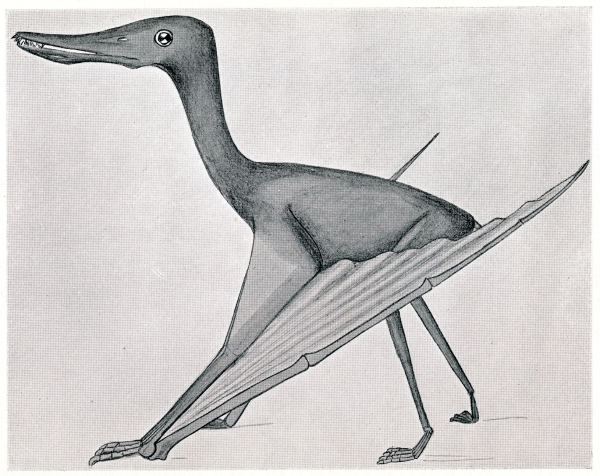

Cycnorhamphus suevicus, by E B J Seeley. Figure 61 from Dragons of the air by H G Seeley, (London, 1901). RS.19118

Cycnorhamphus suevicus, by E B J Seeley. Figure 61 from Dragons of the air by H G Seeley, (London, 1901). RS.19118

I have yet to come across further works by Ethel Seeley, but I wonder whether her foray into scientific illustration might have been inspired by her father’s earlier work with another women paleoartist. This was Gertrude Mary Woodward (1854-1939), daughter of Horace Bolingbroke Woodward FRS, Keeper of Geology at the British Museum (Natural History). Gertrude was selected to undertake the lithographic plates to illustrate Seeley’s work on fossil reptiles in a ten-part series in the Philosophical Transactions, published between 1888 and 1896.

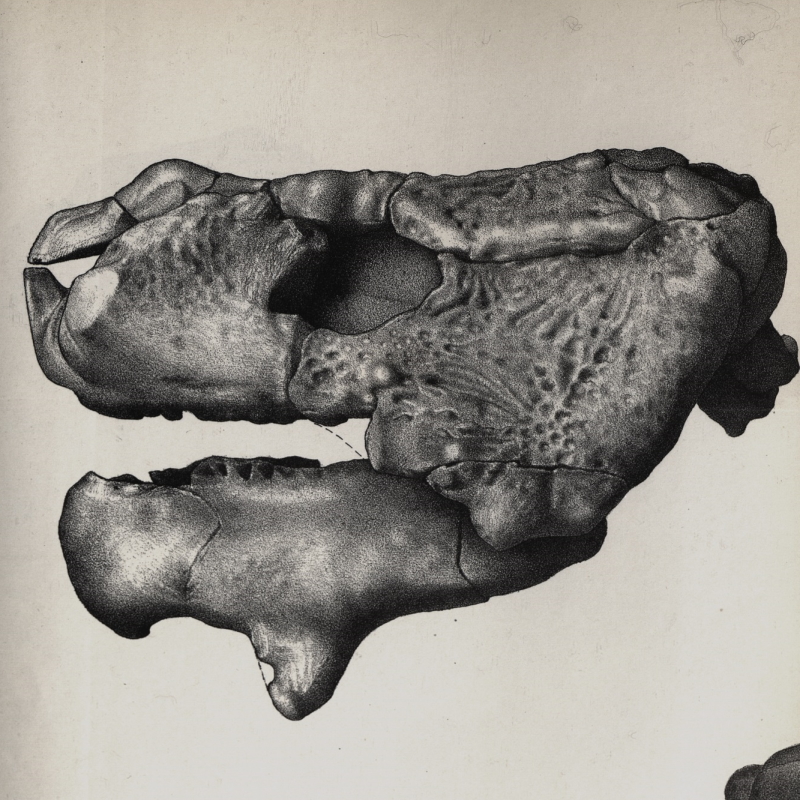

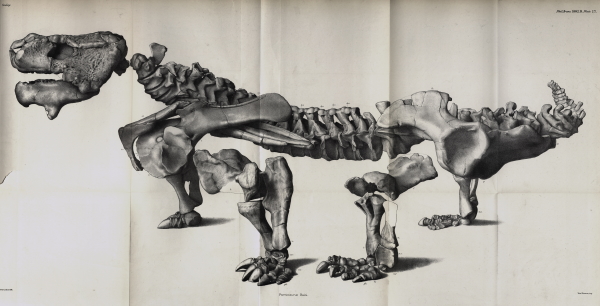

Pareiasaurus Baini, by G M Woodward. Plate 17 from Researches on the structure, organization, and classification of the fossil Reptilia; VII: Further observations on Pareiasaurus by H G Seeley, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol.183 (1892).

Pareiasaurus Baini, by G M Woodward. Plate 17 from Researches on the structure, organization, and classification of the fossil Reptilia; VII: Further observations on Pareiasaurus by H G Seeley, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol.183 (1892).

A year after Gertrude Woodward was initially hired, the Royal Society’s Treasurer, John Evans FRS, was no longer willing to pay the price she charged for her work (see NLB/2/601). It’s revealing to note that Woodward was demanding more than her male counterparts, and it’s clear that she was held in high esteem by her peers for the accuracy and quality of her work. Seeley was keen to hold on to Woodward, and a compromise was made by dividing the work with another printmaker and fixing the price at four-and-a-half guineas for a quarto plate and six-and-a-half for a folding plate. This was half a guinea more than the Society’s going rate for such work at the time, and they only agreed to pay more in exceptional cases.

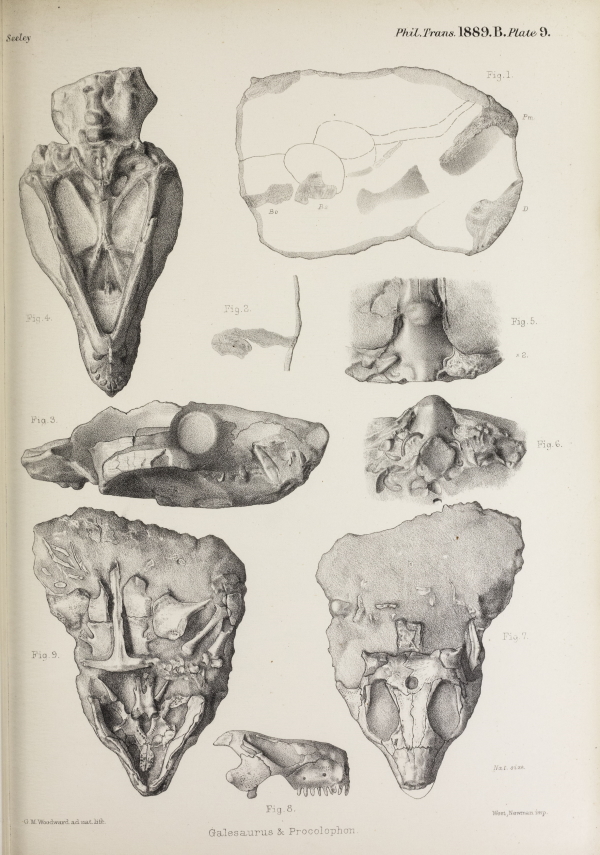

Galesaurus and Procolophon, by G M Woodward. Plate 9 from Researches on the Structure, Organization, and Classification of the Fossil Reptilia; VI: On the Anomodont Reptilia and their Allies by H G Seeley, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, Vol.180 (1889).

Gertrude Woodward went on to create further palaeontological illustrations for the Philosophical Transactions, including On Megaladapis madagascariensis (1894) by Charles Immanuel Forsyth Major FRS and On the skull, mandible, and milk dentition of Palaeomastodon (1907) by Charles William Andrew.

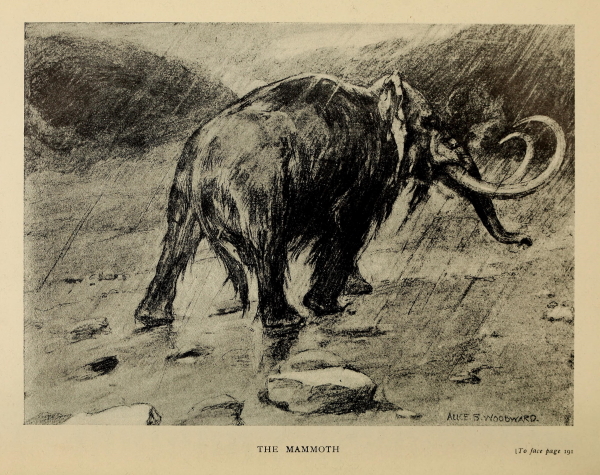

Gertrude was from a scientific dynasty in the fields of geology and zoology, and her sister Alice Bolingbroke Woodward was also an accomplished artist. Alice began her career and funded her education in fine art through illustrating her father’s scientific papers when she was a teenager. She is best remembered for her contributions to children’s books, but her scientific efforts included the illustrations to books on palaeontology by Henry Knipe, Nebula to Man (1905) and Evolution in the past (1912). Her work is credited with being life-like and portraying animals of the past as if they were living.

Twelve of Alice Woodward’s original drawings of extinct animals were exhibited by Knipe at the Royal Society’s conversazioni on 12 May 1909 (PC/3/3/16) and a few weeks later on 24 June (PC/3/3/17). Coincidentally Bonhams sold a collection of 42 original illustrations to Knipe’s two books last December, including 13 by Alice.

‘The Mammoth’, by Alice B Woodward. Illustration to Evolution in the past by Henry R Knipe (1912). Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

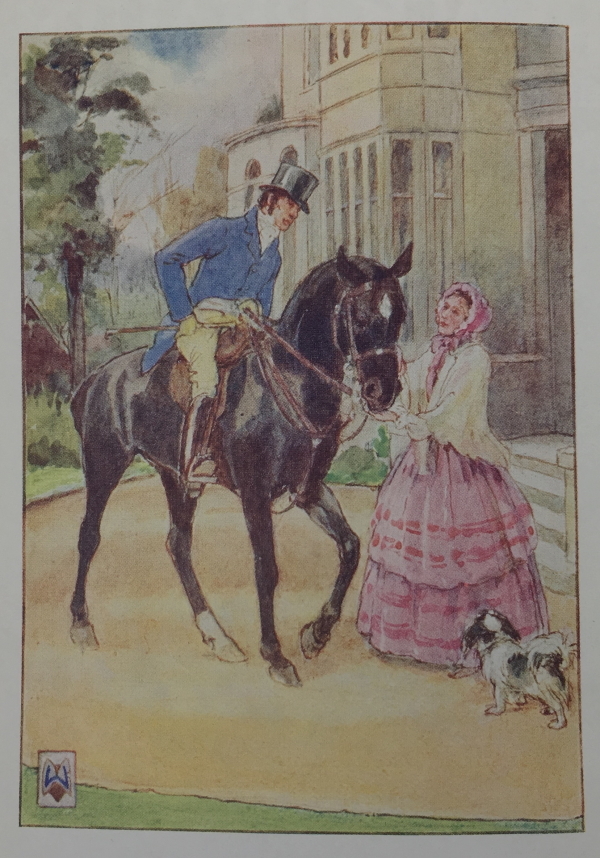

Alice spent the latter part of her career working in a studio formerly owned by Sir Hubert von Herkomer in Sparrows Hearn, Bushey, not too far from my former home. I’m amused to think that her illustrations to Anna Sewell’s children’s classic Black Beauty (1931 edition) might have been influenced by the landscape of my childhood, but it’s also nice to know that a significant contribution to paleoart can be traced to my home town.

Frontispiece to Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty, by Alice B Woodward, 1931 (author's collection)