Why is there a statue of Isambard Kingdom Brunel FRS in a car park in Pembrokeshire? Rupert Baker investigates...

I was pleasantly surprised to bump into one of our Fellows in a Welsh car park recently.

Author’s photo

We were on a family holiday in Pembrokeshire, parking in Neyland at the start of a cycle route. I suppose its name, the Brunel Trail, should have been a clue, but I hadn’t really done my homework ahead of time, not wanting to jinx our trip during a pingdemic. The statue of the great engineer, complete with instantly recognisable stovepipe hat, was therefore an unexpected sighting, and led me to investigate further. What was the connection between Isambard Kingdom Brunel FRS and this peaceful spot on the Milford Haven Waterway?

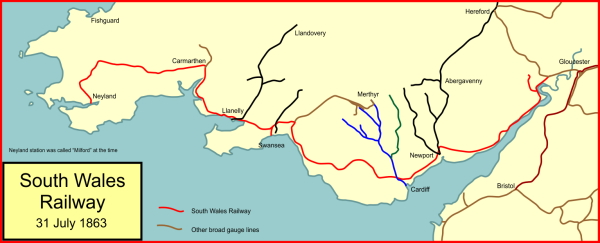

The answer turned out to be rather surprising: according to the history section of the Neyland Town Council website, modern Neyland dates back to 15 April 1856 (a Tuesday) when it opened as the terminus of the South Wales Railway, and the town’s ‘founder’ was Brunel himself. This rail line was sponsored by, and eventually amalgamated into, the larger Great Western Railway project, set up in 1833 as a trade link between Bristol and London (via a plot of land in Acton purchased from the Royal Society – I never knew that!) with the young Brunel as chief engineer. You can see the route of the South Wales line in red on this map, with Neyland at the western end:

Creator: Afterbrunel, on Wikipedia (Creative Commons licence)

Business boomed in Victorian Neyland – renamed New Milford by the railway company – which had formerly been a mere huddle of cottages, all levelled to make way for the railway and port. Steamships departed for Ireland, Portugal and Brazil, from a pontoon designed by Brunel himself, and shops, pubs and hotels opened to cater to the flood of visitors arriving by sea and rail. Sadly, Brunel didn’t live to see much of this – he died of a heart attack in 1859 at the age of just 53, a 40-a-day cigar habit possibly speeding him on his way – but his legacy of great railway and engineering projects has given him a prominent place in British history, as this earlier blogpost explains.

Neyland’s peak lasted for 50 years until, in 1906, a new port for the Ireland route was opened at Fishguard Harbour to the north. Traffic declined, and the Neyland railway terminus closed in 1964, a victim of the Beeching Report. However, as with other former industrial towns, leisure industries have filled some of the void: Neyland now has a thriving marina, dating back to the 1980s, with a café on the Brunel Quay (excellent cakes – I speak from experience) catering to yachties and cyclists alike.

The Brunel Trail itself is a pleasant ride of eight miles or so, starting out from Neyland Marina along the former railbed and joining Sustrans Route 4, which runs from London to Fishguard. After passing the closest remaining station from the old South Wales Railway, at the village of Johnston, the route continues across farmland to Haverfordwest, where we turned and retraced our tracks.

Cycling along Brunel’s old railway route was certainly a less vertical and strenuous experience than my previous bit of Fellow-following in Wales, though on the return leg we did find ourselves pedalling into the wind off the estuary – the cake was well-earned. And as we departed the car park, I gave a final, fond wave to Isambard Kingdom Brunel – let’s hope his statue avoids the fate of its predecessor!

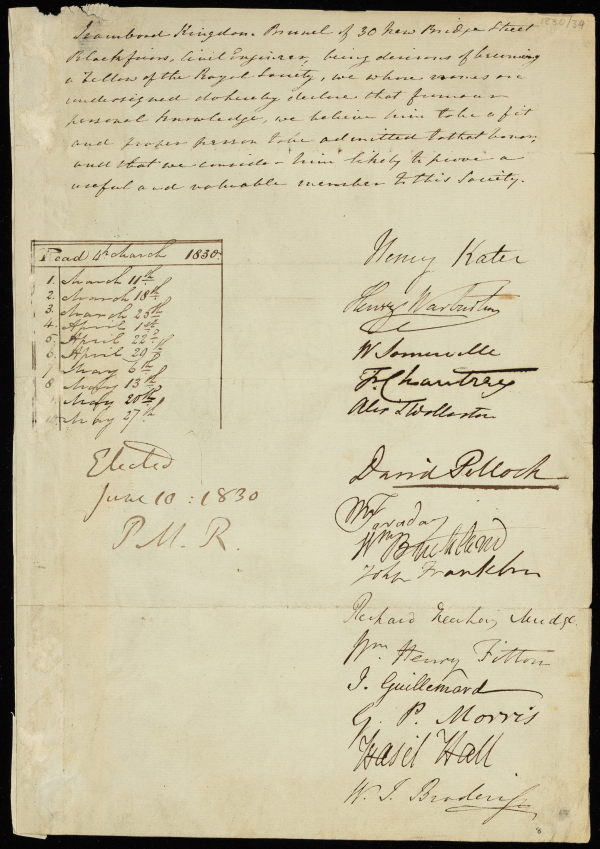

Brunel’s Royal Society election certificate, EC/1830/34