Fiona Amery discusses her winning essay on the topic of Northern Lights aural phenomenon accounts in the 19th and 20th centuries.

The winner of the 5th Notes and Records Essay Award 2021 has now been announced. We spoke to the author, Fiona Amery, to find out more about her winning entry, The disputed sound of the aurora borealis: sensing liminal noise during the First and Second International Polar Years, 1882–3 and 1932–3.

What interested you in your essay topic?

While researching drawings, photographs and other visual representations of the northern lights created in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, I was surprised to find a small number of accounts alluding to ethereal, fleeting and unexplained noises accompanying violent auroral displays. Even more enthralling, reports from such disparate places as the Shetland islands and northern Canada seemed to corroborate one another, all likening the mysterious sounds to a ‘crackling’, ‘whizzing’ or ‘swishing’.

Delving deeper, there seemed to be a palpable sense of scepticism among atmospheric scientists of the nineteenth century, who struggled to identify a possible explanation for the aural phenomenon. I was drawn to the long-standing controversy as to whether the sounds existed objectively, or were the product of the imagination or an Arctic illusion, akin to Polar mirages fooling the eyes. Moreover, I wanted to investigate how trustworthiness and credibility were established within the Arctic landscape, traditionally perceived as a space of uncertainty and otherworldliness within Western histories. The question of auroral sounds was outside of the realm of conventional atmospheric science, and therefore hadn’t attracted a great deal of academic interest, but because it garnered considerable attention during the First and Second International Polar Years (1882-3 and 1932-3), I thought it was worth understanding more about it.

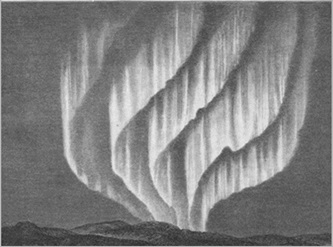

Adam Paulsen’s drawing of low-lying auroral bands, observed to the South-West of his station at Godthaab in South-West Greenland on 15th November 1882.

How does your work explore the role of embodied practices in natural sciences?

My essay shows that the embodied act of listening patiently on cold dark nights for hours on end at the various Polar Year stations in the Arctic was a practice still valued within a scientific culture that prized knowledge produced from precision instruments. The human senses were the sole means of investigating the sounds of the aurora during the Polar Years, which is slightly surprising given the opportunity to transport and use sound recording equipment, particularly towards the later period of the 1930s. This becomes more remarkable when one realises that advanced photographic and spectroscopic apparatus were included in the inventories of expeditions to the Arctic to capture the aurora visually.

What I think is interesting here, is what the reliance on the embodied senses tells us about conceptions of the Arctic itself in the period. The sounds, considered to be most likely fantastical, were bound up with the idea of the Arctic as an eerie, enchanting and almost magical region within the Western imaginary. It was the body as a medium which was relied upon to make sense of the strange auroral sounds, in a region where technologies sometimes proved unreliable and the construction of knowledge was an uncertain project, subject to questions of a spectral, or illusory nature.

What philosophical and scientific difficulties did you see in transcribing the ethereality of the aurora borealis into scientific facts?

Within the source material, the aurora borealis was certainly seen as an object that could never be captured in all its glory, either with pen and pencil or with words. In fact, it’s a trope which is quite relentlessly repeated. As Sophus Tromholt remarked in his 1885 treatise on the aurora, ‘a lovelier spectacle is not given the human eye to behold, he who has not seen it cannot form an idea of its magnificence – it defies description.’ Clearly, the affective and emotive qualities of the phenomenon were considered part and parcel of the observational experience.

Yet, researchers participating in the two International Polar Years did endeavour to record details of the aurora. Its fleeting and variable nature was met with rigorous observational practices. A camera built specifically for auroral photography was employed to capture its forms, overcoming problems associated with the phenomenon’s low luminosity against the dark night sky. Additionally, an atlas was created to categorise its morphology, making it possible to calibrate observations, combatting the difficulties of dealing with an infinitely variable phenomenon.

Sophus Tromholt in Sami clothing standing among the instruments in his outdoor observatory at Kautokeino during the 1882-3 First International Polar Year.

What role did you see for ‘scientific amateurs’ and popularisers of science in developing the understanding of the aurora borealis and polar science?

People considered to be amateurs were surprisingly well-respected within the investigation of auroral sound. This was most likely because researchers of the International Polar Years needed to rely on the experiential knowledge of people living in northern territories, considering noises accompanying displays were very rare and required more than a single year of listening to be heard. Surveys of areas including the region surrounding Chesterfield Inlet in Canada, the north of Norway and the whole of the British Isles contributed to knowledge of the phenomenon in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Shetland Islander, Clement Williamson, corresponded with some of the leading scientists of the era including Sir Oliver Lodge and Professor Carl Størmer (as well as H. G. Wells on the subject of time travel) to discuss and put forward his case for the objectivity of auroral sound. That being said, it was primarily the salaried Polar Year researchers themselves who were trusted with verifying local testimony and tasked with publishing results in the Western scientific idiom.

What are you working on next?

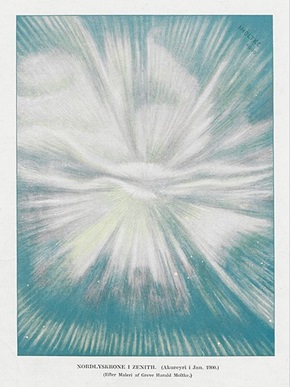

Next, I’m going to be writing a new PhD chapter on drawings of the aurora borealis in the late nineteenth century. To me, Harald Moltke’s pastel and oil paintings that he made on an expedition to Iceland in 1899-1900 are fascinating and beautiful, so I’d like to begin analysing influences on his work and understand the choices of colour and composition that he made. I’m also going to start researching my final two PhD chapters, which will be focused on auroral observation during the International Geophysical Year of 1957-8. Hopefully, I’ll be able to make a research trip to visit some archives and a modern-day auroral observatory in Norway to help inform this work. The themes I’m really interested in surround issues of how to represent atmospheric objects and the reliability of the senses as well as the calibration of instruments across distances, especially in the cold conditions of the Polar Regions. I hope to incorporate these ideas into my upcoming work and beyond.

Harald Moltke’s ‘Auroral Corona’ painting as observed over Akureyri on 1 January 1900, on Adam Paulsen’s second Arctic expedition of 1899-1900 to northern Iceland.

Notes and Records is an international journal which publishes original research in the history of science, technology and medicine. Find out more information about submitting to Notes and Records. The next Notes and Records Essay Award will be in 2023 - look out for an announcement in late 2022.

Image credits:

Author photograph supplied by Fiona Amery; Image 1: Adam Paulsen, ‘Aurora (multiple rayed-bands) observed to South-West from Godthaab on 15 November 1882 at 00h 30m’, drawing in Observations internationales polaires, 1882–83, Expédition Danoise: observations faites à Godthaab (Chez G. E. C. Gad, Libraire de L'université, Copenhagen, 1893), p. 3.; Image 2: Sophus Tromholt, ‘Sophus Tromholt in Sami costume standing among the instruments in his outdoor observatory at Kautokeino’, 1882–3, University of Bergen Library, ubb-trom-038.; Image 3: Harald Moltke, ‘Auroral Corona over Akureyri on 1 January 1900’, Photograph, Danish Meteorological Institute (DMI).