Keith Moore takes a look at the origins of a festive tradition, as well as scientific studies of trees by Royal Society Fellows John Evelyn and Henry John Elwes.

There are various annual competitions around to find the nation’s favourite tree, most recently the Woodland Trust’s 2021 winner – a hawthorn at Kippford, on the west coast of Scotland. Another Scottish tree, the Fortingall Yew, is considered among Britain’s oldest, from the many contenders in the Ancient Tree Inventory. At this time of year, however, the Christmas tree wins out.

The route by which these in-house oddities became part of seasonal culture is a yew tree story too, and a well-known one. The poet (and sometimes science lecturer) Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) recorded country rituals witnessed during his stay in Ratzeberg, near Lübeck in Germany, during the winter of 1798-1799, later publishing an account of them. Besides learning the language and ice-skating, Coleridge was an early English observer of a prototype Father Christmas elf (Knecht Rupert, or Ruprecht), amulets to ward off more unwelcome spirits coming down the chimney, and the custom of placing tapers and paper decorations on yew tree branches, under which gifts might be found. Although known and sometimes copied in England, the idea became mainstream when the Royal Society’s patrons, Queen Victoria and Prince Albert, brought their tree indoors at Windsor Castle in the 1840s. Popularised by engravings, the Christmas tree would become rooted in seasonal celebrations.

Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and the traditional tree, 1848 (anonymous: unknown author, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

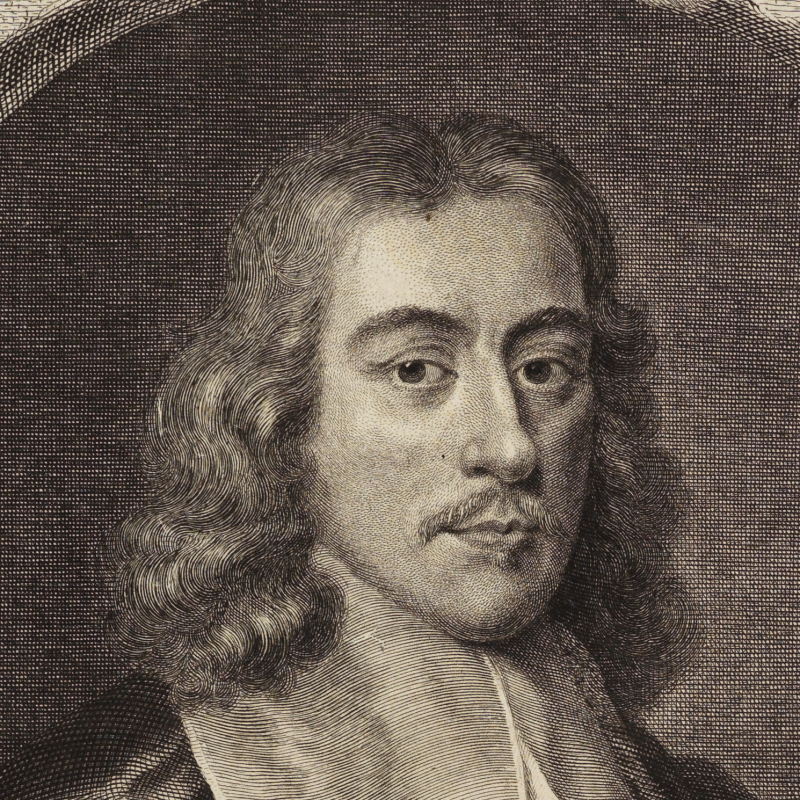

Now, I’m a bit of a Christmas killjoy, and I prefer my trees alive and outside. Happily, there’s a long history of scientific interest in woodland, beginning, for the Royal Society, with our very first book publication, John Evelyn’s Sylva; or, A discourse of forest-trees, and the propagation of timber (1664). Evelyn described many of the standard trees and the uses of their timber in the book: he too was fascinated by very old trees, classical references to woods, and much more besides. Naturally, he mentions that other Christmas stalwart, the holly tree and its traditions: ‘But to say no more of these superstitious Fopperies, which are many other about this Tree, we still dress up both our Churches and Houses, on Christmas and other Festival Days, with this cheerful green and rutilant Berries’.

If Evelyn sounds a tad grumpy about Christmas holly, it’s because in later editions of Sylva he noted the trashing of his estate at Sayes Court by the visiting Peter the Great of Russia: the holly gave him what he described as one ‘impregnable barrier … which I can shew in my now ruin’d gardens at Say’s-Court (thanks to the Czar of Moscovy) … it mocks the rudest assaults of the weather, beasts, or hedge-breakers’. Hardly the stuff of legendary tree stories, and not in the same league as the Boscobel oak that sheltered Charles II in the King’s story to Samuel Pepys, or Isaac Newton’s apple tree!

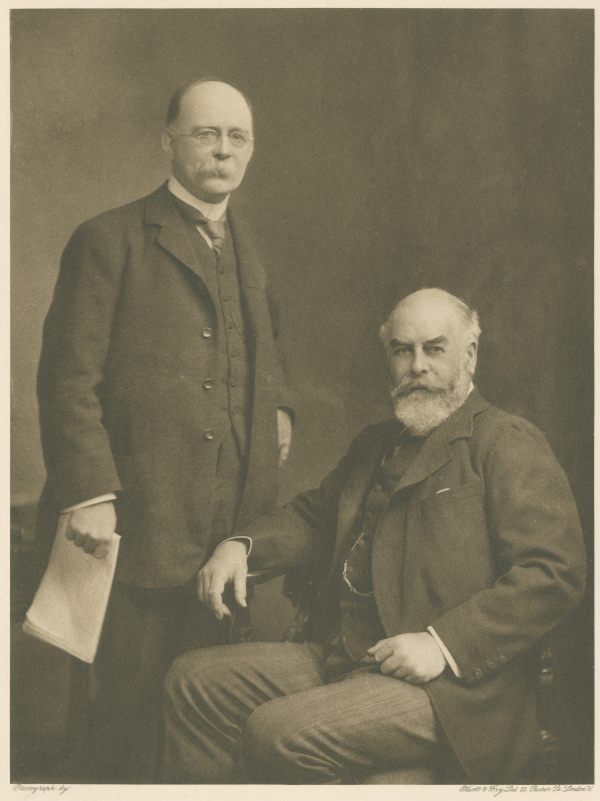

Woodsmen: Henry John Elwes (R) and Augustine Henry (L) c.1905 (RS.11224)

The prize for the Fellow who followed most closely in Evelyn’s interests and visited the most trees must surely go to the naturalist Henry John Elwes FRS (1846-1922). Elwes seems to have been a larger-than-life character: a Scots Guards Captain with a huge physique and a booming voice; an inveterate traveller and apt to go big-game shooting. His scientific pursuits were similarly out-of-doors, taking in botanical and entomological collecting expeditions before he discovered a passion for trees. From the 1880s, Elwes was inspired by the forests of Mexico and the south-western United States and would write a classic text on the subject of British trees and imports from such regions.

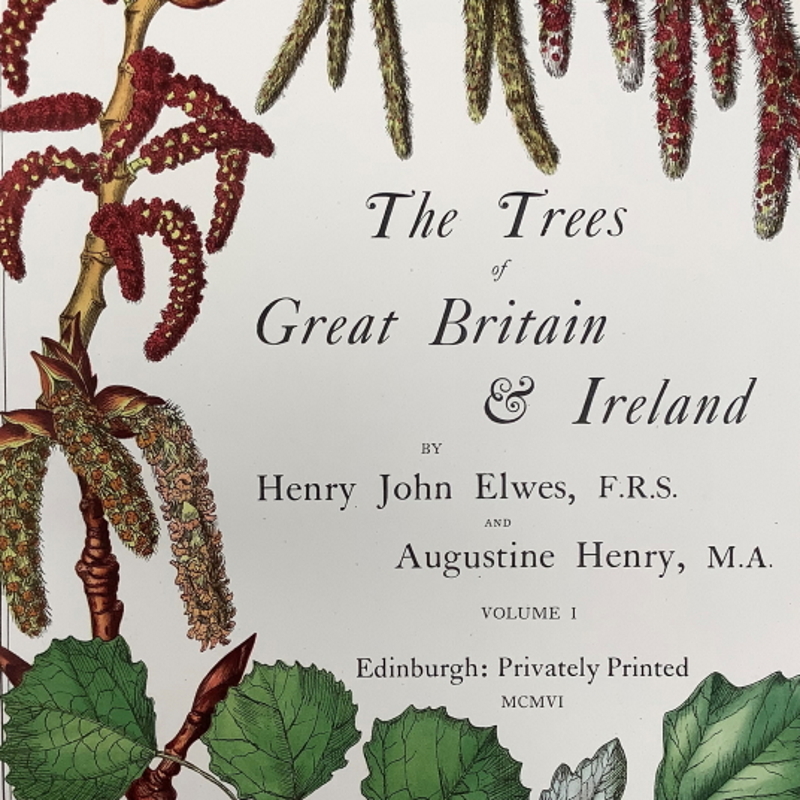

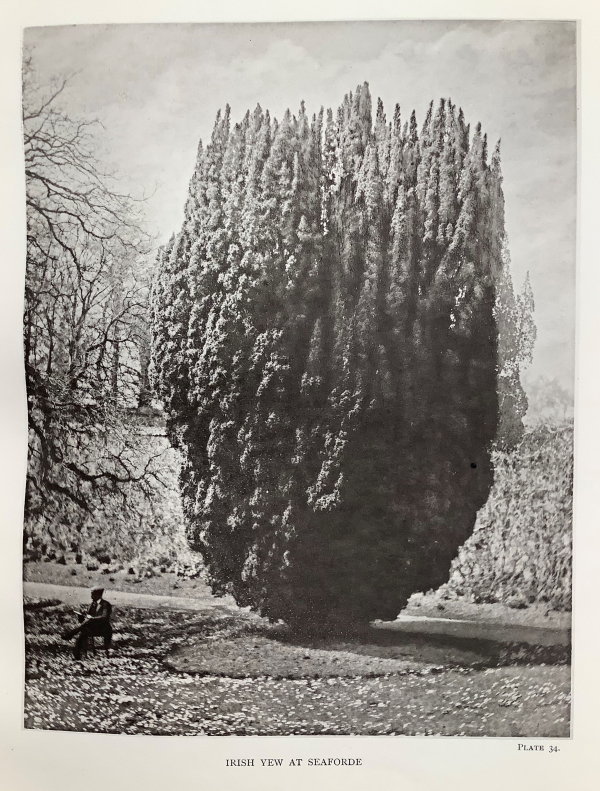

Elwes’s set of volumes, The trees of Great Britain and Ireland (1906-1913), is a comprehensive look at forestry in Great Britain. It was co-authored by the Irish botanist Augustine Henry (1857-1930) and was ten years in the making. Its authors contributed 2,000+ pages of text and commissioned over 400 plates. Elwes allegedly wore out two motor cars on his travels to visit collections and individual trees, and didn’t limit his interest to writing about woodland. He would introduce many new trees into Britain, some as replacements for diseased home species, and paid keen attention to the uses of British woods, in a manner that would have pleased John Evelyn.

‘Irish yew at Seaforde’, from The trees of Great Britain and Ireland

What would Elwes’s favourite tree have been? No doubt he had too many to choose from, but perhaps the Oriental plane still growing at his former estate at Colesbourne in Gloucestershire. As you may have gathered from this year’s Summer Science Exhibition, any old tree is good for carbon capture, so we should value them all. And if you’ve ever visited the Royal Society, you might have spotted one of my favourites – the large plane growing right by the Duke of York Column, and helpfully modelled by University College London. That’s my kind of Christmas tree.