Claire Conklin Sabel investigates a surprising entry in a Royal Society Journal Book index from the 1680s: 'Diamonds cast up by moles in April'.

Moles are born to dig. Their glossy coats are the subterranean equivalent of aerodynamic, helping them glide through the soil to tunnel distances of up to 20 metres per day in search of earthworms. These tunnel networks can be used by several generations, constantly expanded to reach fresh supplies of food. Since moles can eat at least half their bodyweight in worms a day, this keeps them quite busy.

A European mole (RS.13354)

A European mole (RS.13354)

All this displaced dirt has to go somewhere, resulting in the molehills that begin to sprout with increasing frequency in the spring months. And while it may be unpopular with gardeners, moles’ frequent foraging helps to aerate the soil, consume crop-damaging pests and improve soil drainage. It can also turn up treasures that would otherwise stay below ground.

I first encountered this more surprising attribute of moles while researching the role of gemstones in the early Royal Society’s history last year. The index of the Journal Book of the Society’s meetings from the early 1680s noted: ‘Diamonds cast up by moles in April’. This led me to a meeting on 26 November 1684, when Robert Plot FRS (1640-1696) read a letter from one Mr Leigh ‘who is now in Lancashire, with a design of writing the Naturall History of the Country’. Plot had written a popular Natural History of Oxfordshire in 1677, which focused on fossils and minerals, and Leigh likely sought advice on his own project, which was eventually published in 1700.

Robert Plot FRS (RS.11253)

Robert Plot FRS (RS.11253)

Leigh’s letter to Plot remarked on various features of the local landscape. Rather than including moles among more familiar gardeners’ gripes – including ‘a sort of Caterpillers found on Cabbage Leavs’ and ‘maggots found in Pippins’ – Leigh highlighted their contributions to the mineral wealth of the area: ‘We have Roch Allum, Vitrioll, Sulphur, Diamonds which are cast up by the Moles in Aprill, these are not to be discovered though you dig never so deep’.

Diamond particles by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek FRS, 1709 (RS.18931)

Diamond particles by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek FRS, 1709 (RS.18931)

Leigh’s diamonds may have been quartz crystals, akin to the ‘Bristol diamonds’ and ‘Cornish diamonds’ mentioned by other Fellows of the Royal Society as potentially valuable native gemstones. Another possibility is suggested by John Pettus (1613-1685), a mineralogy and metallurgy enthusiast elected FRS in 1663. In his 1670 book Fodinae Regales, a study of Britain’s mineral resources, Pettus observes that moles are respected by both farmers and miners in Derbyshire.

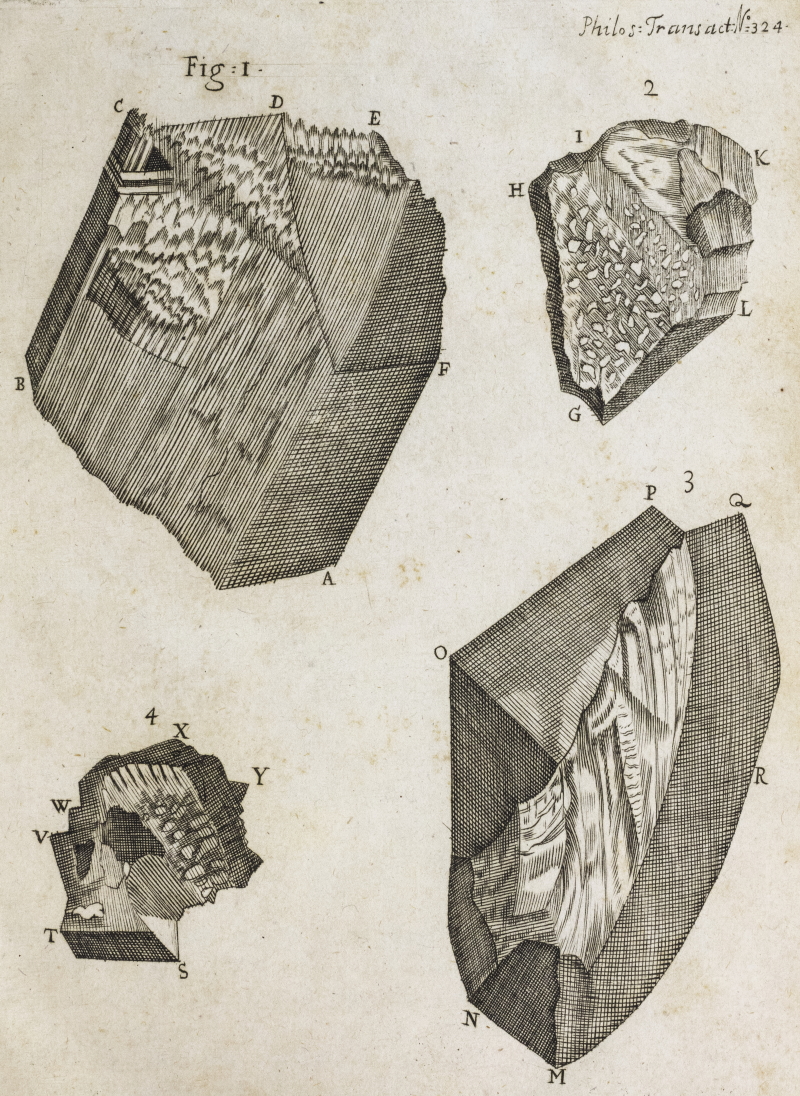

Illustration of 'naked' silver containing Galena lead and quartz, 1752 (RS.10347)

Illustration of 'naked' silver containing Galena lead and quartz, 1752 (RS.10347)

‘Gold, Silver, Tin, Copper, Lead, Iron and Quicksilver’ can be found by ‘Minerals as the Workmen call Leaders, because they usually accompany the Metallick oar, and lead to it’, Pettus reported. ‘Or they are discovered to us either by the nature of Plants which grow over them, by the Plough, by Moles which cast up their shade or glittering earth’. For this reason, he reported, in Derbyshire ‘and other places where Lead abounds, they rarely kill them’.

Moles are the only mammal to live entirely underground, sharing their subterranean world with a host of invertebrates and insects. Ants and termites have a much more ancient and more widely-held reputation as mineral prospectors. They routinely unearth precious substances, from kimberlites – the minerals that do indicate the presence of true diamonds – to gold. While European moles may never discover any such riches, they can turn up fossils and antiquities, buried treasures that cannot be fabricated in a laboratory. These happy coincidences mean that moles can make a cultural contribution, as well as an ecological one, to our gardens and countryside.