A new collection of Biographical Memoirs celebrates the astronomers and astrophysicists who made major contributions to the advance of science in the post-World War II era.

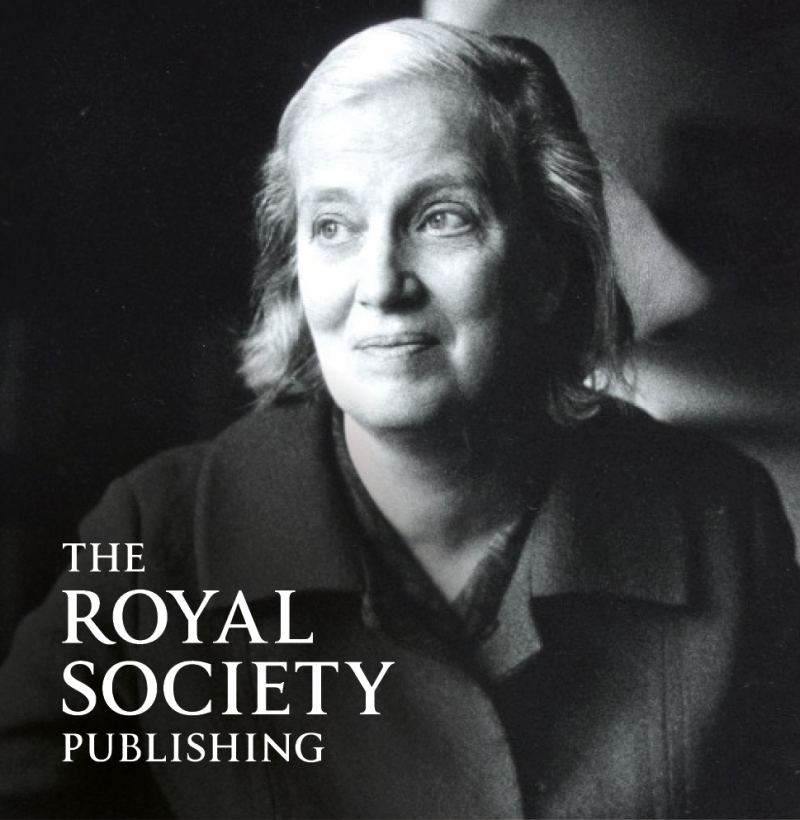

Professor Malcolm Longair, Editor-In-Chief of Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society, introduces a new special collection of memoirs: Astronomy, astrophysics and cosmology.

Modern astronomy, astrophysics and cosmology changed beyond recognition over the post-WWII period. In 1945, astronomy meant optical astronomy and the tools of astronomy were optical telescopes. By the 1960s and 1970s however, astronomy was experiencing golden years of innovation and discovery. The most important developments were the opening up of the complete electromagnetic spectrum for astronomical observation (including observations from space), the electronic revolution, and the huge influx of scientists from other disciplines—particularly physics—into astrophysics.

There are many ways of telling this story, but one approach is to concentrate on the biographies of some of the key leaders of the field, many of whom were Fellows of the Royal Society and whose Biographical Memoirs are now openly available on the Royal Society website. These are authoritative scientific biographies describing the scientific achievements of the deceased Fellows and how they made their advances. By close reading, one gets inside the minds of these outstanding scientists at an accessible level. The emphasis is necessarily upon British and Commonwealth scientists, but the Foreign Members of the Society add greatly to the richness of the story.

The Post World War II astronomical scene

The astronomical scene in the UK was not promising. The country was bankrupt and the UK climate was, to put it politely, not conducive to optical astronomical observation. The Royal Greenwich Observatory was an Admiralty establishment, with the prime objective of keeping time and latitude for navigational purposes. With the facilities available, the Astronomers Royal, such as Richard Wooley, encouraged pure astronomical and astrophysical research, but the UK astronomers could not compete with the USA, which had the largest and most productive astronomical telescopes. The US astronomers became dominant in all aspects of classical optical astronomy and cosmology, as exemplified by the career of Allan Sandage. The result was an exodus of many of the best UK astronomers to the USA, including Wallace Sargent, Margaret and Geoff Burbidge, and Thomas Gold.

There was, however, considerable strength in theoretical astrophysics in the UK, building on the legacy of Arthur Eddington and Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar. Undoubted leaders included Fred Hoyle, Hermann Bondi and William McCrea.

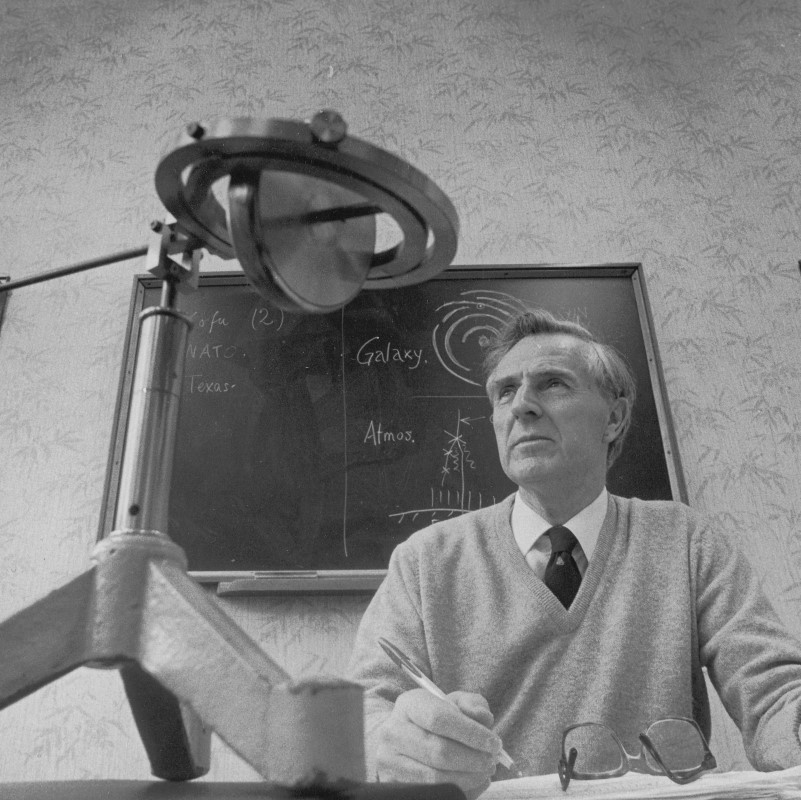

The beginning of the resurgence of UK astronomy came from an unexpected direction. During the War, James Hey had discovered radio signals that interfered with radar, which was crucial for the defense of the nation against bomb attacks and as guidance systems for the UK’s bomber force. After the War, the key players, many of them trained by Jack Ratcliffe, returned to their Universities and began the study of these signals. The leaders of these endeavours were Martin Ryle in Cambridge, supported by Francis Graham-Smith, Tony Hewish and John Baldwin; Bernard Lovell at Jodrell Bank (pictured top), supported by Rod Davies and Robert Hanbury Brown; and Bernard Mills, Paul Wild, Edward (Taffy) Bowen and John Bolton in Australia.

Consequently, radio astronomy developed very rapidly. It was soon discovered that the brightest sources away from the Galactic Plane were very distant extragalactic objects, which was to lead to the discovery of quasars—the hyperluminous nuclei of active galaxies—in 1962-63. It was soon established that these sources had to be powered by supermassive black holes in their active nuclei, the inevitability of their formation in gravitational collapse being established by Stephen Hawking. These discoveries led to major investments in radio astronomy facilities in the UK and Australia.

Institute of Theoretical Astronomy (IoTA) Symposium 1971, Cambridge, UK. Participants included Donald Lynden-Bell (front row, 2nd from the left), Stephen Hawking (front row, 6th from the left), Fred Hoyle (front row, 8th from left), and Margaret Burbidge (right of Hoyle). See a fuller description below.

The 1960s and 1970s were key decades in the development of new approaches to astrophysics. The detection of the emission line of neutral hydrogen in the radio waveband at 1.4 GHz, predicted by Henk van de Hulst at a clandestine seminar during the WWII occupation of Holland, provided a very powerful tool for studying galactic dynamics. This was complemented by the discovery of molecular lines in the radio waveband which led to renewed interest in atomic and molecular astrophysics by theorists such as Alex Dalgarno and Michael Seaton.

At the same time, other wavebands were opened up. The use of space for observations in the UV, X-ray and γ-ray wavebands had been advocated by Lyman Spitzer soon after the War, which proved to be a key step towards the approval of the Hubble Space Telescope project in the 1970s. In the UK, space endeavours were fostered by Harrie Massey and Harry Elliot through their involvement in the creation of a UK space programme and their advocacy for the European Space Agency (ESA). Among the most significant of these developments was the opening up of the UV waveband through the involvement of Robert Wilson, culminating in the great success of the International Ultraviolet Explorer.

Artist's impression of the International Ultraviolet Explorer. Image from NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute.

The discovery of the Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation in 1965 proved to be a turning point in modern cosmology. Hoyle and Roger Tayler revived the idea of the primordial origin of helium and light elements in the Universe, which became one of the keystones of contemporary cosmology. The numerous contributions of Soviet theorists to cosmology were led by Yakov Zel'dovich.

Theoretical astrophysics expanded enormously from the 1960s onwards, stimulated by the many dramatic discoveries of new ways of tackling old problems. Some highlights include Leon Mestel’s pioneering researches in cosmic magnetism, Bernard Pagel’s seminal work on the use of chemical abundances as cosmological probes, Donald Lynden-Bell’s remarkable work on stellar dynamics and many other areas, and Franz Kahn’s diverse research in astrophysical gas dynamics. Plasma physics became a key tool for astrophysics, making use of Ian Axford’s studies of the heliosphere as applied to double radio sources and Martin Kruskal’s deep insights into magnetic reconnection in plasma physics. Special mention must be made of Dennis Sciama whose unprecedented catalogue of graduate students includes Stephen Hawking, Roger Penrose, Martin Rees and Brandon Carter.

No record of this remarkable period would be complete without remarking on the extraordinary contributions to the public understanding of astronomy by Patrick Moore, whose The Sky at Night programme he presented once a month for more than 50 years.

This brief essay can only highlight the areas in which these distinguished scientists made their most important discoveries, but many of them contributed very significantly to many other fields. My lasting impression of this galaxy of astronomers is their huge diversity of approaches, their many different family backgrounds and the very different ways these excellent scientists used their talents. These all enrich the discipline enormously.

Read the memoirs discussed here and more in the new Astronomy, astrophysics and cosmology collection. All memoirs are published online as they are ready before being compiled into two volumes per year. Sign up for alerts or keep an eye on our website for new memoirs as they appear.

Image credits:

Lovell Telescope, Jodrell Bank Observatory. By Mike Peel, Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, University of Manchester, Wikimedia CC BY-SA 4.0.

Participants in the 1971 IoTA symposium to celebrate the sixtieth birthday of Willy Fowler. The identifications are by row number (R) from the front row and from the left (l) or right (r). Geoff Burbidge (R2, l5) is standing next to Martin Ryle (R2, l6). In the front row, there are Donald Lynden-Bell (FRS 1978; R1, L2), Stephen Hawking (FRS 1974; R1, l6), Fred Hoyle (R1, l8), Margaret Burbidge (R1, l9), Willy Fowler (R1, l10), Sarah Burbidge (R1, l11), Martin Rees (FRS 1979; PRS 2005–2010; R1, r7), Wallace Sargent (FRS 1981; R1, r6), and Roger Penrose (FRS 1972; R1, r3). Further back there are Kip Thorne (R3, r6), John Archibald Wheeler (ForMemRS 1995; R4, l7), Bill McCrea FRS (R4, r6), Bob Wagoner (R4, r4), Tony Hewish FRS (R5, r7) and Al Cameron (R6, r8). (Photography by Edward Leigh 1971. Courtesy of Lafayette Photography, Cambridge, and the Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge.)

Artist's impression of the International Ultraviolet Explorer. Image from NASA and the Space Telescope Science Institute.