In the third of our series of articles celebrating Black History Month 2022, Diana Davis looks at the life of South African veterinarian Dr Jotello Soga, highlighting his important work in combatting rinderpest, an infectious viral disease of cattle.

How we tell our histories matters in more ways than we usually imagine.

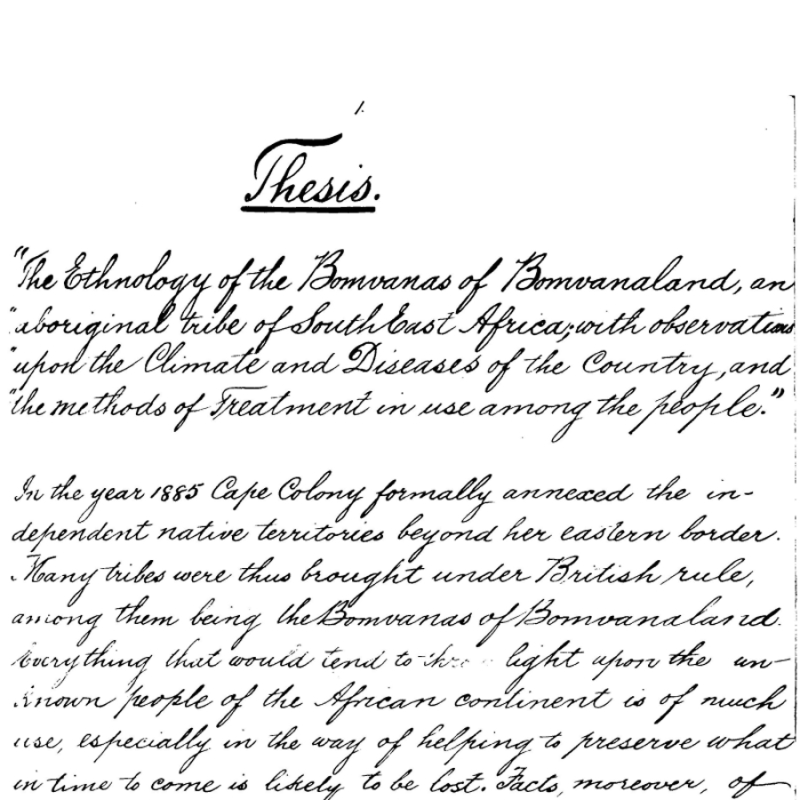

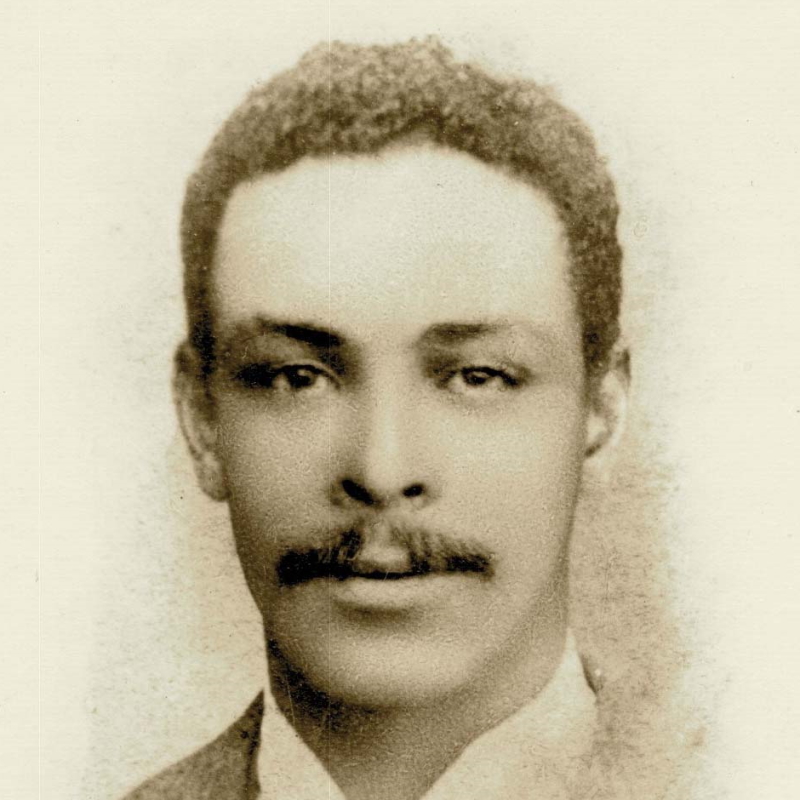

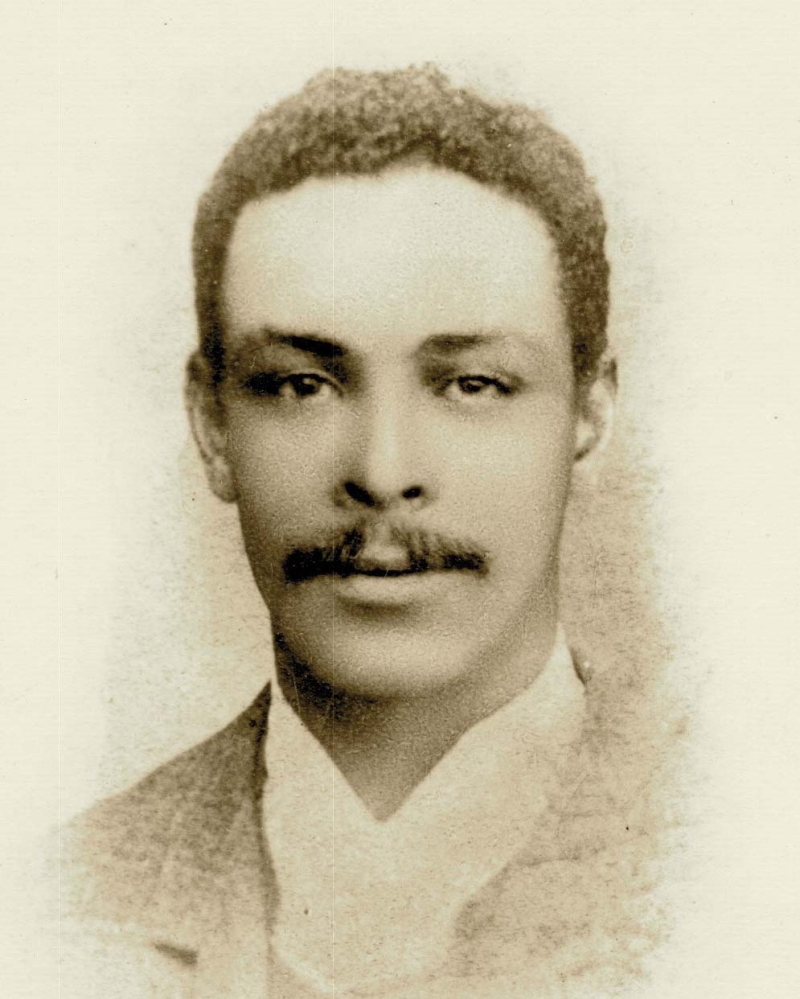

The first formally trained South African veterinarian (MRCVS, 1886) was a Black man, Dr Jotello Festiri Soga, a pioneer in veterinary toxicology and inoculation, and a key player in the containment of rinderpest in the region. I’ll be discussing Jotello Soga at the Royal Society on 21 October, at the African scientists in colonial and postcolonial contexts, 1800-2000 conference – tickets are still available here.

The history of veterinary medicine in South Africa, as in most of the rest of the world, has been a history primarily of white men as written by other white men. The famous veterinarian Dr Arnold Theiler, for instance, claimed in 1914 that the first formally trained South African veterinarian was Dr P R Viljoen - who qualified as a vet about a quarter of a century after Soga, in 1912. This despite the fact that he had met and worked with Soga in the 1890s and was aware of his credentials.

Dr Jotello Soga (Public Domain via https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/jotello-festiri-soga-1865-1906/)

Dr Jotello Soga (Public Domain via https://www.blackpast.org/global-african-history/jotello-festiri-soga-1865-1906/)

Jotello Soga was the youngest son of Reverend Tiyo Soga (from a noble Xhosa family) and his Scottish wife Janet Burnside, and brother of William Anderson Soga, the subject of our recent blogpost. Jotello was born at Mgwali Mission in the Transkei in 1865, and educated in Scotland, as were his three older brothers. He entered Dick’s Veterinary College in 1882 and qualified as an MRCVS (the first Black member of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons) in 1886.

Only three years after returning to South Africa, he was appointed as Assistant Veterinary Surgeon for Cape Colony in 1889. Appointed eight months after veterinarian Dr John Borthwick, he was the second in a team that grew to eight members over the next few years. He was much esteemed by the Colonial Veterinary Surgeon, Dr Hutcheon, and was soon earning the same rate of pay as his white colleague Borthwick. Like his father, Soga married a Scottish woman, Catherine Chalmers, and they had three daughters.

Within a year of joining the Cape Colonial Veterinary Service, Soga had identified the toxic plant Nenta (Cotyledon ventricosa) that had been causing disease and death among goats and other animals for many years, and proved by experiment that it causes the disease locally called ‘Nenta’ and ‘Krimpziekte’ a form of cerebro-spinal meningitis. Soga, furthermore, devised a most effective treatment for the debilitating disease. This was a landmark accomplishment and represents the birth of veterinary toxicology in South Africa, a field that did not become well-established until the first decades of the twentieth century. The results of his experiments formed the content of his first article, published in January 1891 in the Agricultural Journal of the Cape of Good Hope.

After several years of inoculating cattle for CBPP (Contagious Bovine Pleuro-Pneumonia), locally termed ‘Lung-Sickness’, Soga conducted a six-month-long series of formal experiments on this widespread disease in 1894. At that time CBPP was the most devastating livestock disease in the colony. He successfully developed a method of vaccination using a needle on the tails of adult cattle and a nearly 100% effective and safe method of drenching calves that vastly improved prevention of this disease. So successful were his results that they were published as a separate booklet as well as in article form in several other venues due to popular demand.

Yet it is in Soga's attention to rinderpest that we see, perhaps, his most prescient, brilliant, and avant-garde character. In 1892, three years after rinderpest broke out in East Africa, Soga published two short articles in the Agricultural Journal of the Cape of Good Hope, in which he warned of the likely devastation that the virus would bring. In these, Soga predicted the rapid spread of the disease towards South Africa and warned that if proper measures were not taken, ‘I make bold enough to say, that more than two-thirds of Colonial cattle will succumb to its ravages’. Today's academics estimate that rinderpest wiped out 80-90% of African livestock and an untold number of wild ungulates. Soga appears to have been the first to warn of rinderpest coming to South Africa and noted that it was the ‘new Colonial enemy’ and that ‘lung-sickness and redwater are simply fools to it’. He rightly advocated for a policy of cull and slaughter enforced with ‘a stringent law, and a heavy penalty for breaking the same’.

Soga also played a key role in the eventual eradication of rinderpest from South Africa, although it is not often noted in the literature. It was he who brought a rinderpest-infected cow to the Colonial Bacteriologist, Dr Alexander Edington, who had set up a mobile laboratory to deal with the outbreak. From this cow, Edington, with Soga's assistance, grew the viral culture that was then provided to Robert Koch ForMemRS to begin his research. This early viral culture also formed the basis of Edington's more effective 'serum inoculation' vaccination method. Koch, however, later developed his famous ‘bile method’ of vaccination for rinderpest. Soga, furthermore, was the veterinarian who told Koch of the terrible losses in the ‘Native Areas’ where rinderpest killed tens of thousands of head of livestock. Using Koch's bile vaccination method, along with the 'serum inoculation' method, millions of head of livestock were vaccinated and rinderpest was eventually eradicated in the region.

During the ‘stamping out’ phase of containing the rinderpest epizootic, Soga was frequently sent to the ‘Native Territories’ and to farms to shoot and kill thousands of head of livestock, sometimes killing hundreds in a single day. Part of the reason was that Soga was half Xhosa and could speak with many of the local livestock owners. A few of the other colonial veterinarians were also sent to help with this containment procedure, including Hutcheon, the head of the service, who also noted the exhausting and depressing nature of the task. As a result of this gruelling work, Soga's health broke down and he eventually retired from government service in 1899, with a pension from the government. After a few years of working on farms, he died at the age of only 41, in December 1906. He was commended by the British High Commissioner, Lord Milner, for his special services in combating rinderpest.

Only recently, after many years of obscurity, have Soga's outstanding contributions begun to be recognized. At the University of Pretoria, the Faculty of Veterinary Science named its library in his honour in 2009, and the ARC-Onderstpoort Veterinary Institute created the Jotello Soga Ethno-Veterinary Garden. The South African Veterinary Association (SAVA, formerly Cape of Good Hope Veterinary Association) that he helped to found in 1905 now awards the ‘Soga Medal’ annually in ‘recognition of exceptional community service rendered by a veterinarian or a veterinary student.’

Writing histories in ways that provide as full a picture as possible of remarkable and influential people like Soga, rather than minimizing or silencing them, has the power to inspire new generations of students to equally important and remarkable work. We should do so more often and continue to decolonize veterinary history.

I am indebted to the inspiring work of Jesse Lewis, Clare Boulton (RCVS), Heloise Heyne and the late Thelma Gutsche.