New research published in Royal Society Open Science investigates black widow venom resistance in lizards.

A recent paper in Royal Society Open Science investigates black widow venom resistance in lizards known to prey on the spider. Lead author Vicki Thill tells us more…

Tell us about your study

The idea for the study came from my collaborator and graduate advisor, Dr. Chris Feldman, who had read a short article from the 1930s which suggested that southern alligator lizards could serve as a biological control of black widows for urban areas in California. The author of that paper, legendary western herpetologist Raymond Cowles, explained the lizards’ voracious appetite for widow spiders, but never linked that to spider venom resistance. When I joined the lab, I decided this was the perfect project because it hit all my favourite topics – namely herpetology, ecology, and evolution – and had been left unstudied for almost 100 years. The potential in this study system fascinated me, and I was eager to drive it forward.

We chose three lizard species based on their known or expected interactions with black widows. Two are known predators: one of which commonly eats black widows (southern alligator lizard) and one that is known to at least occasionally eat black widows (western fence lizard). The third is a small-bodied lizard that is known to be prey of black widows (common side-blotched lizard). Based on these interactions, we expected that southern alligator lizards and western fence lizards would perform the best after injection with venom, while the side-blotched lizard would move much slower.

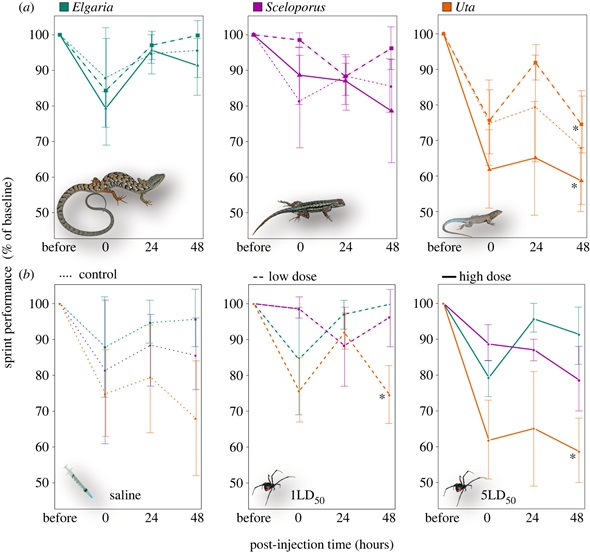

Sprint performance - Figure 1 from 'Preying dangerously: black widow spider venom resistance in sympatric lizards', Thill et al.

We evaluated resistance to spider venom at two different scales, measuring whole animal performance and muscle tissue response. Our whole animal resistance assay is meant to quantify the ecologically relevant consequences of envenomation for individuals bitten by a spider. Does death ensue immediately? Is there reduced movement ability, leading to increased risk of predation or environmental exposure? Evaluating resistance at the tissue level, on the other hand, gives a direct physiological measure of the impacts of envenomation, even if venom effects are masked at the whole animal level. For example, some western fence lizards were able to maintain their normal sprint speed even after injection with venom, but tissue-level damage was significant.

We found a gradient of resistance, consistent with our expectations. Southern alligator lizards tolerated doses of black widow spider venom (five times the mouse lethal dose) as if they had not been injected; western fence lizards performed well at the whole animal level, but showed some tissue damage, and side-blotched lizards were affected both at the whole animal and tissue level. But even the common side-blotched lizard, which was most affected out of the three lizard species, fared exceptionally well compared to mammalian models.

Why is it important to study chemical ecology and these predator-prey relationships?

Studying chemical ecology can lead to medical breakthroughs, including novel treatments of both envenomation and unrelated diseases or health issues. Ecologically, antagonistic species interactions can help us understand not only community dynamics and structure, but also coevolution and the evolutionary pressures responsible for adaptive features. Reptiles are often overlooked, especially those that are frequently encountered in urban areas – but they all have a story to tell, and something to teach us if we just take the time to ask.

What’s the future for this research?

There’s so much more to be uncovered in this system – the exact mechanism of resistance, for example, and how broadly distributed venom resistance might be across the lizard evolutionary tree. We have just begun to scratch the surface. While southern alligator lizards were the star of the show, western fence lizards and even common side-blotched lizards tolerated the powerful venom of black widows. It makes us wonder if all lizards possess some innate resistance to a wide variety of arthropod venoms, or if venom resistance is limited to, and driven by, predator-prey interactions between specific lizard-arthropod pairs.

Vicki Thill, presenting early data at the Joint Meeting of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, Rochester, New York, 2018. Credit: Vicki Thill

From an early-career researcher perspective, how was your research experience?

Starting a new project from the ground up was intimidating, but I had a wonderful lab group, graduate advisors, collaborators, and more that helped me piece everything together. For every roadblock, there was a solution; I just needed to find the right paper to read, or right person to ask.

How was your experience of publishing with Royal Society Open Science?

Publishing with Royal Society Open Science was a breeze. The constructive reviewer feedback and editor comments helped us refine and improve our study, and the process was very quick.

Read all Royal Society Open Science articles for free and find out how to submit your own research.

Main image: Southern alligator lizard (Elgaria multicarinata). Credit: Bob Hansen