In our fourth and final article linked to Black History Month 2022, Rebecca Martin discusses how historians can expand their research practices to include a wider range of historically excluded voices.

As Black History Month draws to a close, many historians may be thinking about how to expand their research practices to include a wider range of historically excluded voices. This is often no easy task; the historically marginalised are, unsurprisingly, conspicuously absent from the archives. In this short blog, I will share with you from my own experience a few of the pitfalls and obstacles that you might face when trying to incorporate a wider range of historical actors into your research, and some of the strategies that can be used to work around these issues.

The main pitfall any historians of historically marginalised communities will find, especially when consulting materials of British societies and offices, is that these communities are also marginalised within the record itself. This scarcity of record is of course a reflection of the contemporary social and political power of these communities and individuals, but also of archival collection policies and practices that have persevered until much more recently.

Archival weeding, in which materials deemed irrelevant are removed in favour of saving space, has been guided by the values and social context of the archivist. This is something to remember if known sources are found to be missing and can provide an interesting story in and of itself. More often than not, however, historians do not enter an archive knowing what they will find, and it is often impossible to tell what is missing from an archive without the help of a previous catalogue (and sometimes even with one!).

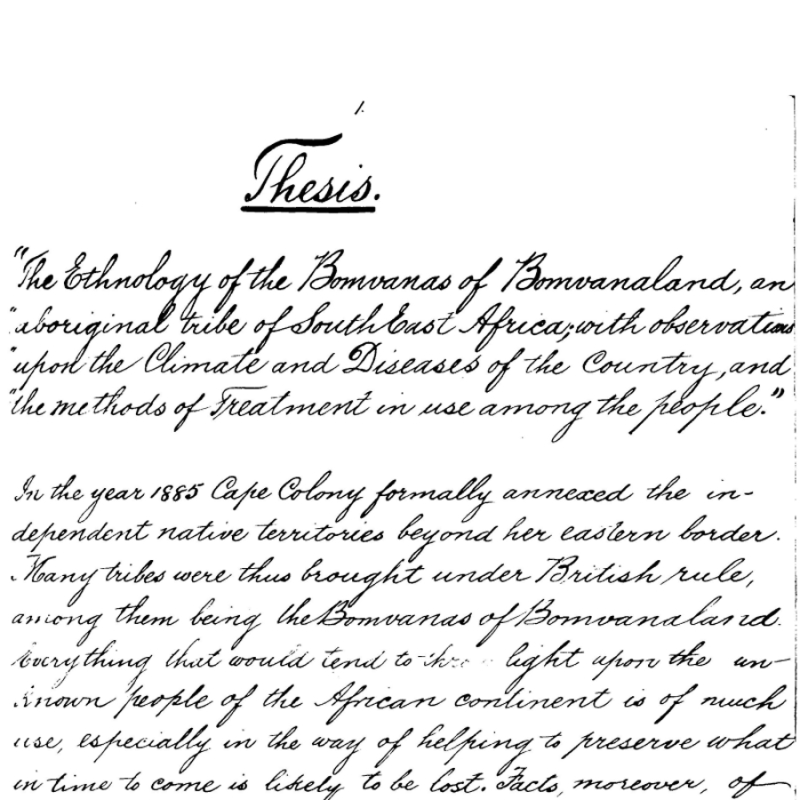

One obvious approach to this problem of scarcity is, simply put, volume; to search diligently for the needle in the haystack. This requires patience and perseverance, with the risk of little reward. During the course of just one month of research into the circulation of scientific knowledge about the body between Britain and India between 1860 and 1920, funded by a Lisa Jardine Award of the Royal Society, I looked at no less than 192 individual Royal Society archive items – as well as consulting the original card catalogue and the Society’s year books and annual reports – and 64 bound volumes of material at the British Library. In each, I often wanted a single letter or line, to check whether any sliver of information had been overlooked in the creation of the catalogue.

The work of Miranda Kaufmann on Black members of British society within the Tudor period, to give just one example, shows how successfully this work can be done. In my own research, I found evidence of a slight shift in tone between official Royal Society communications with British nationals living in India and Indian nationals, with membership enquiries from Indian nationals rebuffed with fewer pleasantries. A single document from the records of the India Office arguing for parity in pay for native and European staff within the Indian Medical Service revealed details of the arguments used to support pay disparity. Another showed that the revered anatomical model maker Joseph Towne had produced a number of anatomical models for the Grant Medical College in Bombay, models which may have been understood to show the white body as a medical norm. Meanwhile, a Report of the Scientific Advisory Board of the Indian Research Association from 1943 indicated that the association was then conducting its own research into the comparative physical fitness of Indian, American, and English populations, with the additional intention of examining the usefulness of fitness tests designed in England and America for application in India.

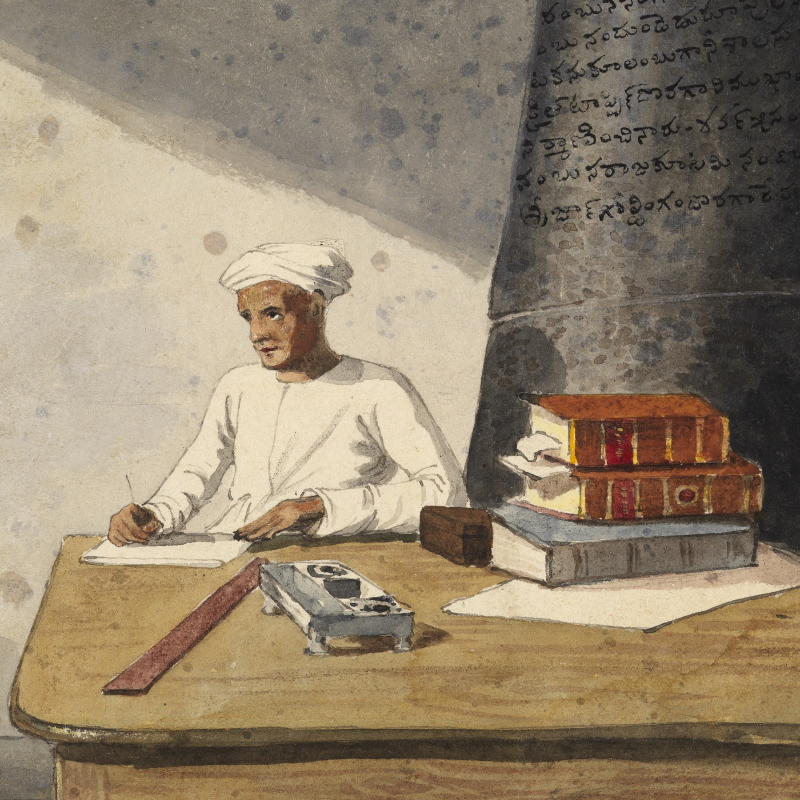

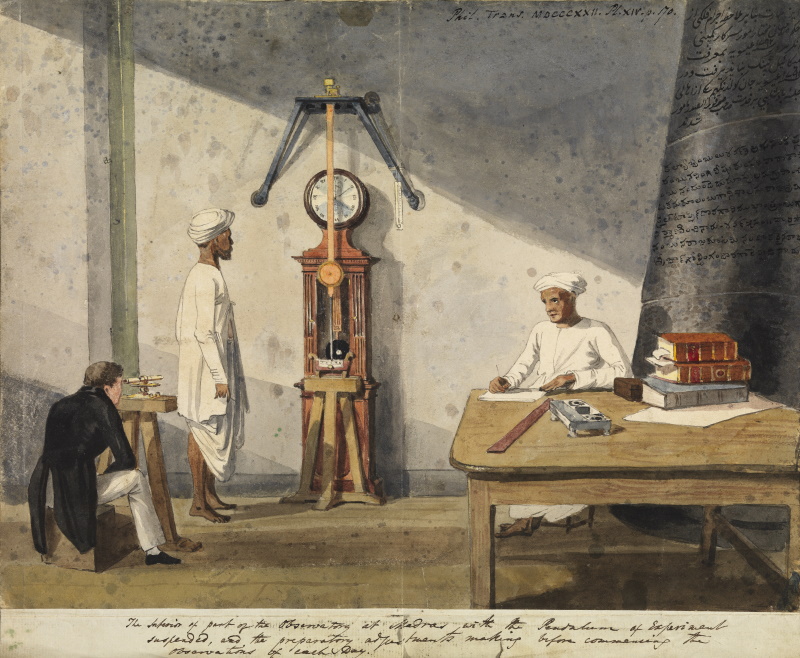

Madras Observatory interior by James Basire III, RS.8719

Madras Observatory interior by James Basire III, RS.8719

However, simply increasing the quantity of archival materials to sift through is not the only way to approach this scarcity. It is important to remember that absences can also speak volumes and that finding nothing can sometimes tell us almost as much as finding something. In the case of my research project, the absence of Indian nationals on a committee regarding health in India illustrates the contemporary low perception of Indian expertise in this area and a belief in the superiority of British expertise and decision-making.

This understanding of absence is part of the practice of ‘reading aright’; a methodology used specifically to address this issue of scarcity. Reading ‘aright’ asks us to read between the lines. It requires a knowledge of the context, in this case contemporary discussions around race and racial difference, and particularly an understanding of specific language and how it is used within this context. For example, knowing the intricacies of western debates about grouping individuals by race or nation in this period means that we do not accidentally dismiss those who claimed there was not ‘sufficient data […] for constructing national groups of the nations’ as anti-racists. Using this methodology, we can begin to understand not only what the archives contain but also the shape of what is missing from them. This skill is particularly useful when approaching the history of material objects, often used to explore the history of marginalised peoples beyond the written record.

Useful as these archival techniques are, however, a point which cannot be stressed enough is that historians must go beyond British/western archives to fully recover the voices of colonised and marginalised individuals. Apart from budgeting for international travel within funding applications, this means that scholars should make room in the budget for document translation or the hiring of additional academics who speak the languages of the geographical location(s) they are researching. It is by going beyond the well-trodden sources, both by ‘reading aright’ and looking at materials written in a larger range of languages, that we can begin to reconstruct some of the histories of marginalised and colonised individuals that have been erased.