A new exhibition at the Royal Society places the work of art critic John Ruskin in the context of developments in science and photography, as curator Professor Sandra Kemp explains.

In the nineteenth century, scientific observation in fields including astronomy and meteorology was being transformed by new optical devices, new printing technologies and new aesthetic styles. This in turn placed a spotlight on the role of visuality and visual instruments, forms of visual evidence, and questions concerning the authority of images and the kinds of image that could serve as scientific standards.

‘John Ruskin and the Science of Sight’, a new exhibition at the Royal Society, places Ruskin’s work alongside that of his scientific contemporaries. It explores ways of representing and communicating scientific discovery through experimentation with photography, and with optical devices such as the microscope, telescope, stereoscope and camera lucida.

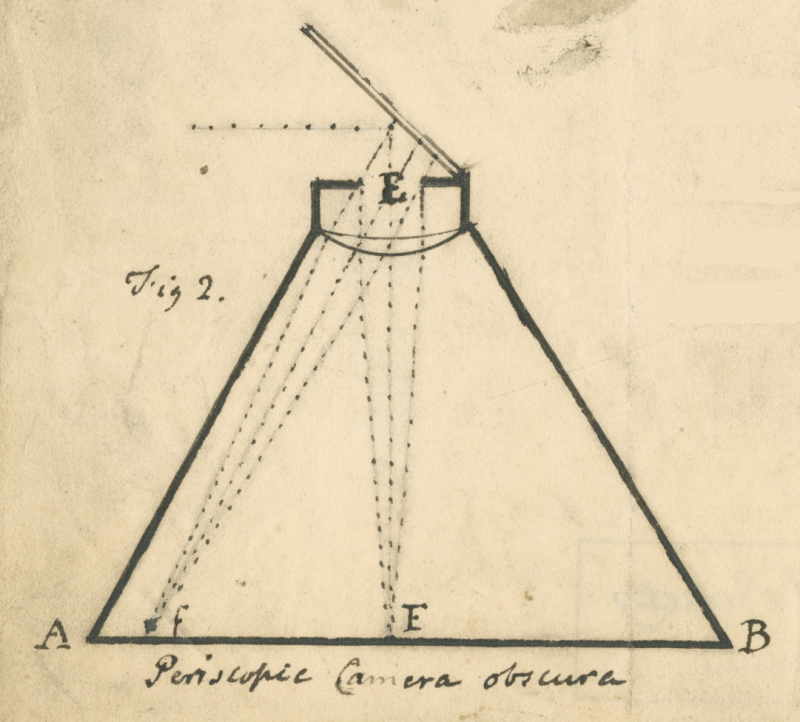

William Hyde Wollaston FRS, Periscopic camera obscura 1812 (PT/73/3/4, detail © The Royal Society)

William Hyde Wollaston FRS, Periscopic camera obscura 1812 (PT/73/3/4, detail © The Royal Society)

As the foremost art critic of the time, and an artist who deployed the latest technologies, Ruskin cultivated what he called ‘the instrument of sight’ and explored developments in optics to observe the world with great clarity. Throughout his life Ruskin’s writings and artworks explored the complexity of visual experience. He sought to extend the uses of science to art, and art to science.

Photography – ‘the most marvellous invention of the nineteenth century’, according to Ruskin – is at the heart of the exhibition, including a letter in which William Henry Fox Talbot FRS described the early stages of this new process of ‘photogenic drawing’:

‘… spreading on a sheet of paper a sufficient quantity of the nitrate of silver; and then [setting] the paper in the sunshine, having first placed before it some object casting a well-defined shadow. The light, acting on the rest of the paper would naturally blacken it, while the parts in shadow would retain their whiteness.’

![Caleb Burrell Rose, Two specimens of fern leaf 1840 [?]](/-/media/blogs/2022/10/ruskin-heart-sight/ruskin-heart-sight-3.jpg) Caleb Burrell Rose, Two specimens of fern leaf 1840 [?] (MS/223/24 © The Royal Society)

Caleb Burrell Rose, Two specimens of fern leaf 1840 [?] (MS/223/24 © The Royal Society)

By 1839, both Talbot and Louis Daguerre had unveiled their photographic methods, with Daguerre asserting: ‘This important discovery, capable of innumerable applications, will not only be of great interest to science, but it will also give a new impulse to the arts’.

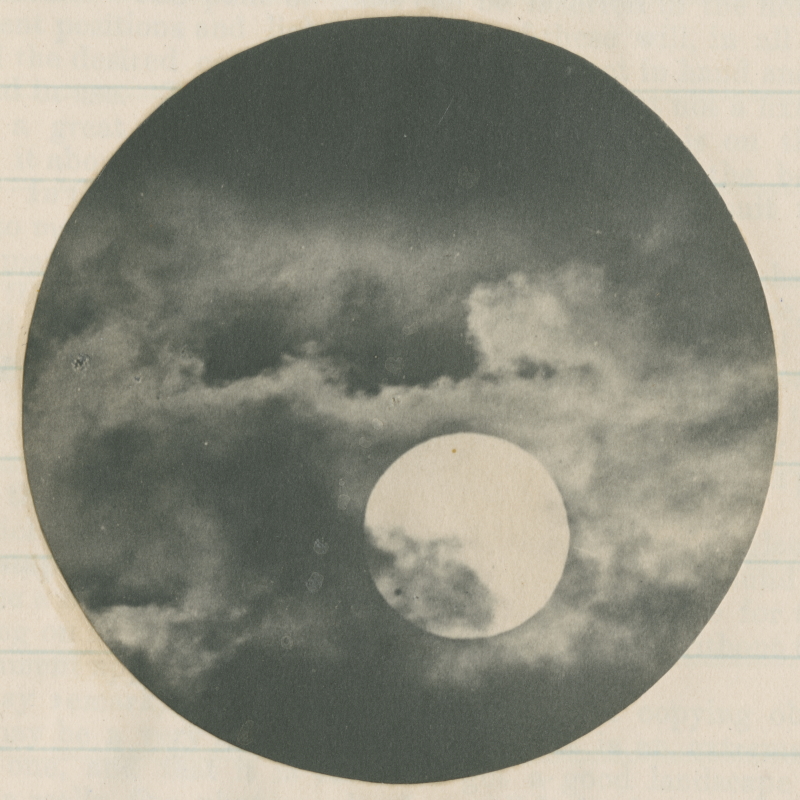

In 1849, Ruskin, with his assistant John Hobbs, was the first to produce a ‘sun-portrait’ of the Alps, using the daguerreotype process. Scientists also briefly adopted this method: at the Great Exhibition of 1851, John Adams Whipple and George Bond received a gold medal for a daguerreotype of the Moon displayed at Crystal Palace. As Ruskin wrote to his father from Venice in 1845, the unprecedented objectivity and levels of detail furnished by the daguerreotype provided new forms of visual and temporal record:

‘more valuable than any sketch can be by way of information … It is very nearly the same thing as carrying off the palace itself; every chip of stone and stain is there, and there is no mistake about proportions … I have been walking all over St Mark’s place today, and found a lot of things in the daguerreotypes that I never noticed in the place itself’.

John Ruskin, Venice. The Ducal Palace and the Piazzetta c.1846-1852 (© The Ruskin, Lancaster University)

John Ruskin, Venice. The Ducal Palace and the Piazzetta c.1846-1852 (© The Ruskin, Lancaster University)

Despite its extraordinary potential, Ruskin became increasingly critical of photography – and of science – as the act of seeing became separated from wider sensory responses. This was part of a growing disillusionment with what he regarded as the destructive environmental impact of the utilitarian application of science and the divorce of science from religion.

John Ruskin, Frederick Crawley, Ardon (Valais). Gorge de la Lizerne 1854 (1996D0076) © The Ruskin, Lancaster University)

John Ruskin, Frederick Crawley, Ardon (Valais). Gorge de la Lizerne 1854 (1996D0076) © The Ruskin, Lancaster University)

In The eagle’s nest (1872) Ruskin contrasts a ‘mechanical’ definition of sight associated with science with the ‘sight’ of art. This comes through the ‘soul’ of the eye rather than its ‘lens’, or what Ruskin called ‘heart-sight’, and his view that visual evidence led to experience that couldn’t be quantified or understood. In this respect, Ruskin’s view was closer to the twentieth- and twenty-first-century understanding of seeing. As Richard L. Gregory FRS wrote in Eye and brain: the psychology of seeing:

‘Yet what we see, and what we know, or believe, can be very different. As science advances, differences between perceived appearances and accepted realities become ever greater.’

Frederick William Pavy FRS, Osazone (glucazone) crystals 1893 (AP/69/10/14 © The Royal Society)

Frederick William Pavy FRS, Osazone (glucazone) crystals 1893 (AP/69/10/14 © The Royal Society)

‘John Ruskin and the Science of Sight’ will be at the Royal Society from 5 October to 9 December 2022. To visit please email library@royalsociety.org

The exhibition is the third in a series of exhibitions co-curated by The Ruskin, the Royal Society and Brantwood. Key works in these exhibitions may also be viewed online:

You can view more digital exhibits on Ruskin and science on Google Arts & Culture:

The art of abstraction: Ruskin's perspectives

The skies are for all: Ruskin and climate change

Miniature mountains: Ruskin and geological artistry

Top image: Arthur Roope Hunt, Transit of Venus, 6 December 1882 (45424 © The Royal Society)