Continuing our series of articles celebrating Black History Month 2022, Suryakanthie Chetty tells the story of the first indigenous western-educated medical doctor in South Africa.

In the first of a pair of articles linked to our conference on 21 October, African scientists in colonial and postcolonial contexts, 1800-2000, conference speaker Suryakanthie Chetty looks at the life of William Anderson Soga, hailed as the first indigenous western-educated medical doctor in the region that would become South Africa.

In 1836, the geologist and surveyor Andrew Geddes Bain recorded his encounter with a Xhosa man attempting to use a plough. For Bain this was an encouraging sign of the efficacy of British influence that would transform the Xhosa into a ‘civilised’ and modern people. Just over fifty years later, in the wake of decades of vicious conflict that took place between settlers and the Xhosa on the expanding eastern frontier at the Cape, an article written in the Cape Monthly Magazine disparaged Xhosa capability, initiative and agency in adopting the values of progress. The Soga family is framed by these antithetical views held by settler society.

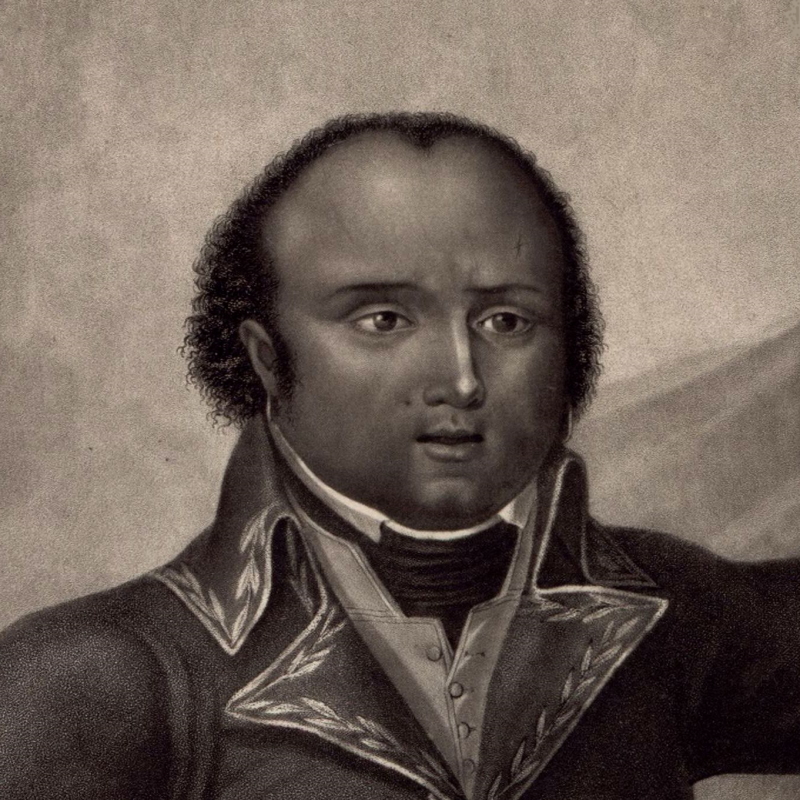

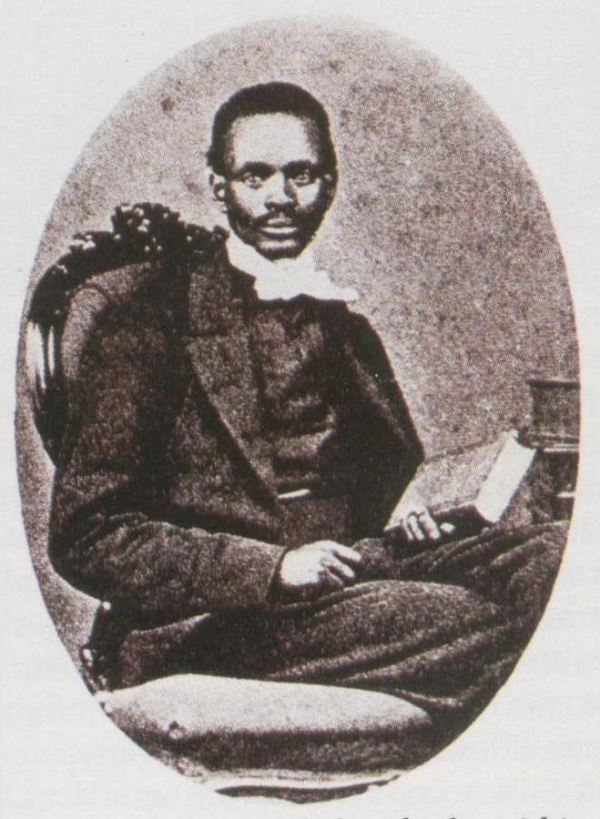

Old Soga was the Xhosa man encountered by Bain, the first to embrace modern irrigation techniques and the use of a plough, participating in a market economy. An advisor to a Xhosa chief, Old Soga straddled the worlds of ‘tradition’ and the ‘modern’. His son Tiyo Soga was educated at the Tyumie mission school and then at Glasgow University, ordained as a Presbyterian minister, married a Scottish woman and returned to South Africa as a missionary. As a British subject, Tiyo was aware of the advantages of embracing the ethos of progress yet, confronted by hostile settler society, he nevertheless understood that there would be limits to assimilation. It was this that impelled him to have his sons educated in Scotland.

Tiyo Soga (Wikimedia Commons)

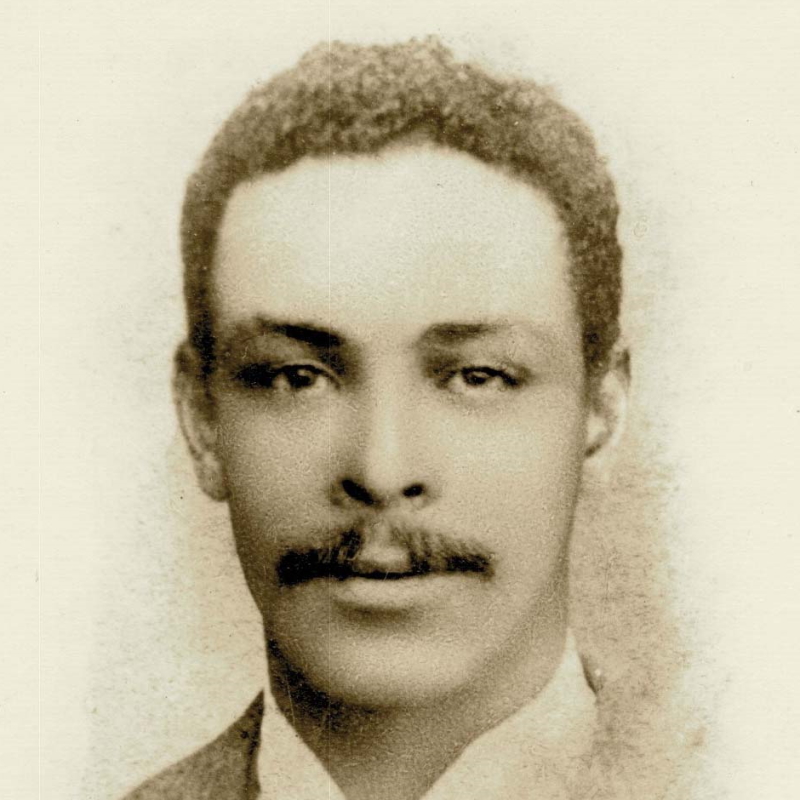

William Anderson Soga was born in 1858, just two years after his parents’ return to South Africa. Named after a Presbyterian minister and the first of seven surviving children, he and his two younger brothers were educated in Scotland. William Anderson was twelve when he enrolled at the Dollar Academy. He subsequently studied at Glasgow University and was awarded his medical degree in 1883, becoming the first South African Black doctor. Like his father he, too, would become a missionary under the aegis of the United Presbyterian Church. He married Mary Agnes Meikle and returned to South Africa where he was based at the Miller Mission in the Eastern Cape.

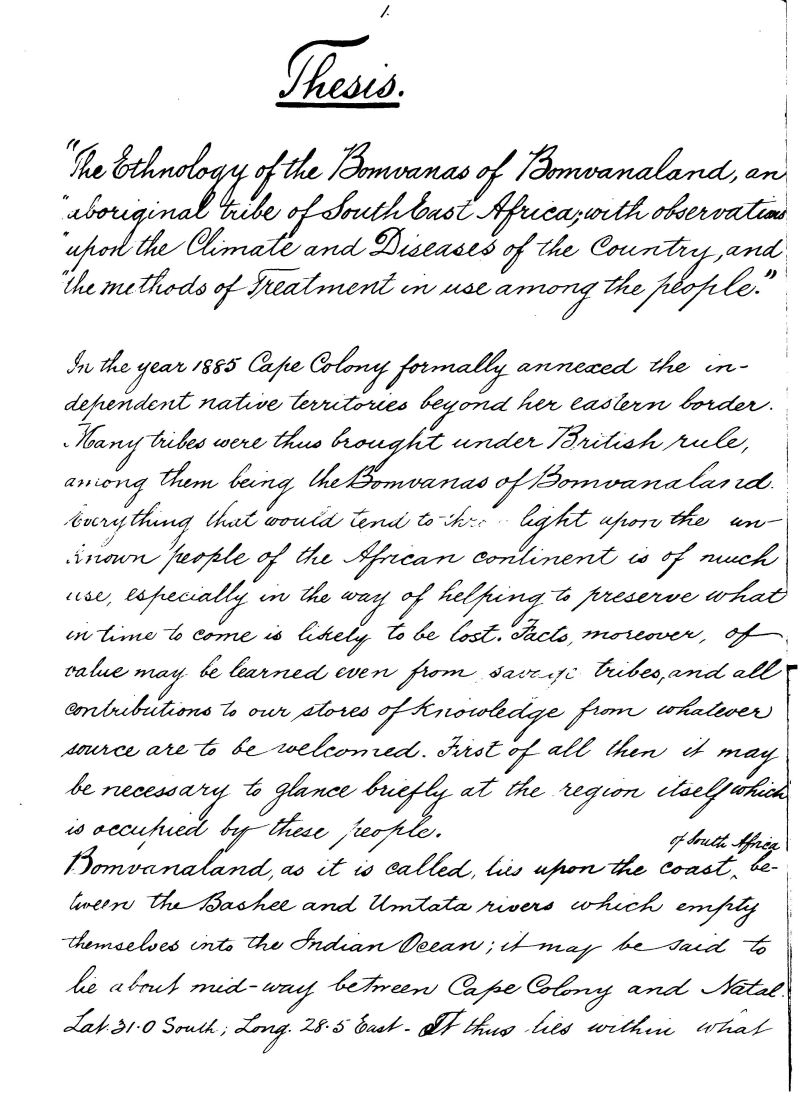

While he prioritised his evangelising mission, the dearth of medical doctors in the region meant that William Anderson had to combine both missionary and medical duties, a combination that proved so onerous that he suffered a breakdown in 1891. His location at the Miller Mission however presented him with the opportunity to observe at first hand an ethnic group called the Bomvana, and it was this group that formed the subject of his dissertation submitted to the University of Glasgow:

(source: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/73985/1/1894SogaMD.pdf)

(source: https://theses.gla.ac.uk/73985/1/1894SogaMD.pdf)

Less a medical treatise than an ethnographic one, ‘The Ethnology of the Bomvanas of Bomvanaland, an aboriginal tribe of South East Africa; with observations upon the climate and diseases of the country, and the methods of treatment in use among the people’, was a description of the indigenous healing practices of the Bomvana. In his exposition, William Anderson demonstrated his own uneasy position in South African society. While he acknowledged the efficacy of Bomvana herbal remedies, he valorised western medicine, contrasting it to the workings of the witchdoctor, the epitome of irrationality, superstition and capriciousness; a figure reviled by missionaries and colonial administrators as representative of the ‘barbarism’ of indigenous society.

Yet William Anderson was all too aware that his writings also recorded a significant moment in the history of the Bomvana – he was preserving for posterity the lifestyle of a group that would be changed irrevocably by its encounter with the forces of modernisation and progress. There is a sense of ethnic pride in his dissertation – the nobility of the Bantu-speaking peoples of which he formed a part, their use of language and their intellect, all of which meant they had the potential to thrive in the new world to which they were being exposed. Yet they were ‘in a transition state from heathenism to civilisation’ leaving them vulnerable to diseases due to changing living conditions and the demands of that civilisation such as migratory labour to the mining centres of South Africa.

For William Anderson, coming from a family that was an exemplar of that shift, modernity was a double-edged sword although he fervently and optimistically believed that it would ultimately be the saving of his people. After a career spanning both the medical and the evangelical, William Anderson Soga died in 1916. Like the Bomvana, his life demonstrates an uneasy state of transition at a time when medicine was linked to empire. Over the course of the next century however, Black western-trained medical practitioners would play increasingly assertive roles in South African political life – Abdullah Abdurahman, AB Xuma and Yusuf Dadoo. And fifty years after William Anderson’s death, it would be Steve Biko’s formative experiences as a medical student that would lead to the Black Consciousness Movement and a new era of radicalisation in Black protest politics in South Africa.’

Our next article will tell the story of William Anderson’s younger brother, Dr Jotello Festiri Soga, the first formally trained South African veterinarian. If you’d like to hear more on the Soga brothers and other African scientists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and on the shaping of European science by colonial and postcolonial contexts, do come along to our conference on 21 October – you can book here.