Louisiane Ferlier finds accounts of previous earthquakes in Syria and Turkey in the collections of the Royal Society Library.

Following the devastating earthquakes in southern Turkey and north-western Syria, the daily news comes with a heartbreaking litany of lost lives – a total of over 50,000 at the time of writing. Subsidiary tremors are further compounding the fear and damage. The lives of millions who live along the East Anatolian fault line have been transformed irremediably by the shaking earth.

Syria and southern Turkey feature throughout our collections in the Royal Society Library, and I wanted to dedicate my blog to some accounts of previous earthquakes in the region. People are, of course, more important than buildings, but their personal stories of loss have survived only rarely. They can be reconstructed, to an extent, through historical images and descriptions of the millennia-old buildings which have been destroyed, and therefore the cumulative impact on the region’s population.

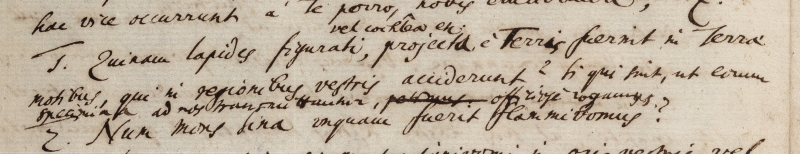

The historical region of the Levant is a cradle of civilization with layer upon layer of archaeological treasures. It was a key trade route from which the English profited via the Levant Company, establishing trading zones known as ‘factories’ from Aleppo to Smyrna. As a result, curiosity about Syria began early at the Royal Society. In 1668 its first Secretary, Henry Oldenburg, sent the British consul in Aleppo a series of enquiries which begin with ‘whether there are any stones indicative of the Earth having trembled or erupted in the region’:

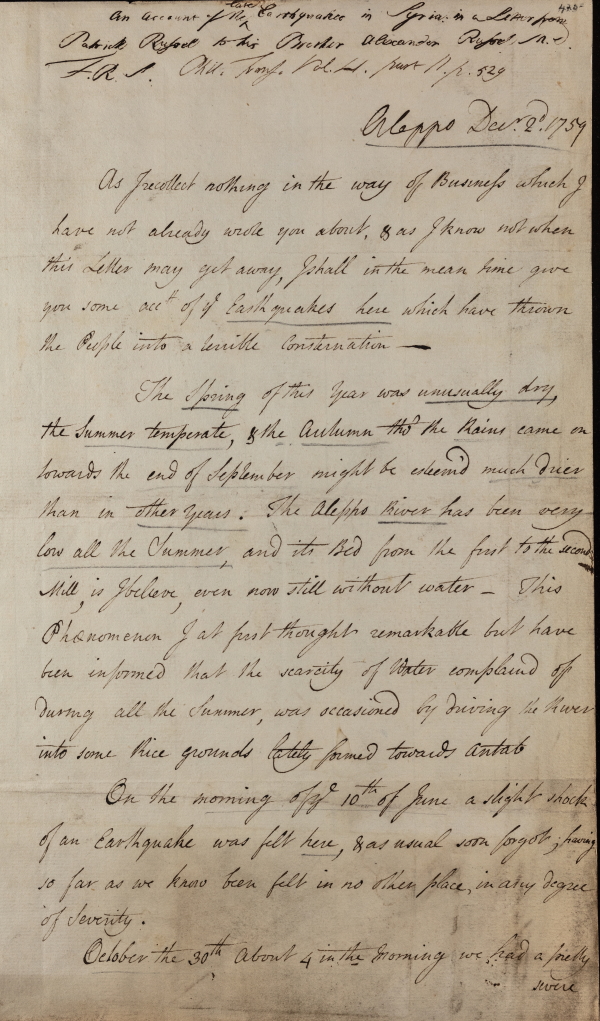

In the eighteenth century, the Society received a letter entitled 'An earthquake at Aleppo' from Patrick Russell to his half-brother Alexander, who had previously written a full Natural history of Aleppo, securing his election as a Fellow of the Royal Society. In the letter, published in the Philosophical Transactions the same year, Patrick Russell recounted in detail the series of shocks experienced across Syria and Turkey from June to December 1759:

If Aleppo was lightly damaged with only ‘some of the oldest minarets having suffered’, as with the recent earthquakes, the city of ‘Antioch’ (today’s Antakya) was severely affected with ‘many houses […] thrown down, and some few People killed’. Damascus was also devastated:

‘The third of the City was thrown down and of the People, numbers yet unknown perish’d in the ruins – the greater part of the surviving inhabitants fled to the fields, where they still continued, being hourly alarmed by slighter shocks which deterred them from reentering the city or attempting the relief such as might yet be saved by clearing away the rubbish’.

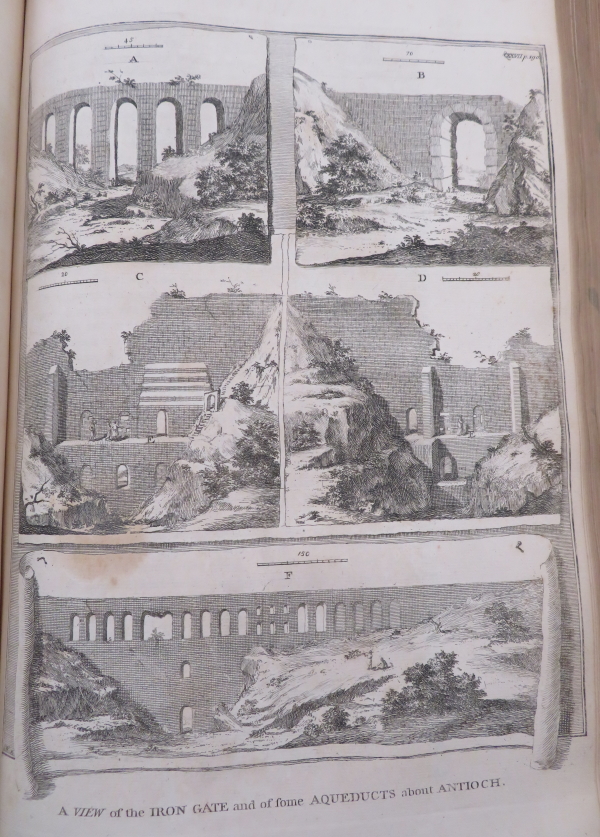

If seismic activity is a constant thread in the modern history of Syria, many historical buildings had withstood the shocks for centuries and millennia, until this month. In his large 1743 Description of the East, traveller Richard Pococke (whose index contains an entry on ‘Earthquakes’, as shown above) notes the damage to the ancient walls of the city of Antioch. Many of the aqueducts still standing in 1743 in the illustration below dated from the Roman period, and portions of the walls even earlier, from the Seleucid era when Antioch was capital of the empire.

From Pococke's Description of the East volume 2

Only sections of the walls remained in Antakya after demolition campaigns in the nineteenth century, and it would not be surprising to hear that the recent quakes have destroyed what was left. With millions of people affected, the loss of historic buildings is far from an emergency, but many of those landmarks are places of worship central to the lives of the people of Antakya and the region. For instance, the Habib-I Neccar Mosque and the Antioch Orthodox Church, respectively Turkey’s oldest mosque and the world’s oldest church, were destroyed.

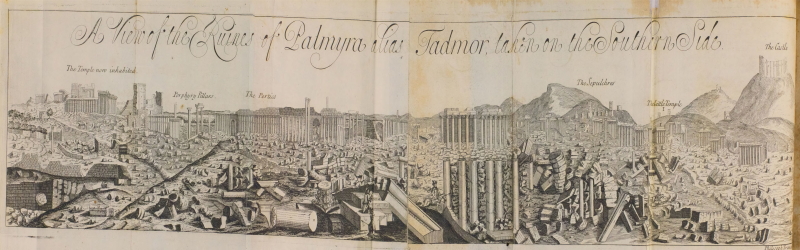

The damage from the civil war to the ancient city of Palmyra is well documented, and since seeing the extent of the destruction I wondered if the seventeenth-century panorama of the city in our collections (below) could become helpful documentation for Syrian archaeologists and museum owners. Now, I wonder if any of the early accounts could help seismologists understand patterns of activity along the fault line, and if the images of the countless historical buildings in the region we hold could be of any help when the time for reconstruction comes.

From 'Some account of the ancient state of the city of Palmyra' by Edmond Halley, 1695

From 'Some account of the ancient state of the city of Palmyra' by Edmond Halley, 1695