Ellen Embleton tucks into the culinary content of the Royal Society's collections, and discovers some unusual experiments in cookery.

A recent enquiry gave me cause to think about one of my favourite things, food, in the context of the Royal Society’s collections.

Our archives and books are teeming with culinary content, from investigations into the fundamental nature of food, its constituents, farming, harvest, and preservation, to simple recipes. Its prevalence is perhaps unsurprising given the essential role of food in our day-to-day lives; however, it does make a summary of the subject challenging.

I’ve therefore opted to approach it through the lens of one facet of the collections I work closely with: our fine artworks. Many former Fellows whose likenesses now adorn the walls of the Society’s home in Carlton House Terrace undertook food-based experiments at some point in their careers. Representing our seventeenth-century portraiture, we have Robert Boyle FRS (1627-1691):

Boyle by Johann Kerseboom (d.1708) and John Riley (1646-1691): RS.9546 and RS.9547

Boyle by Johann Kerseboom (d.1708) and John Riley (1646-1691): RS.9546 and RS.9547

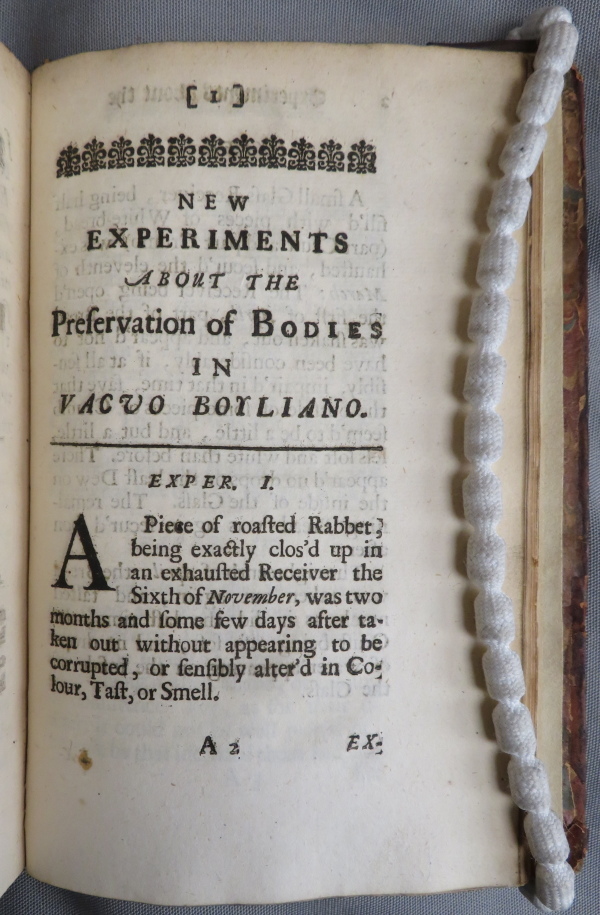

Boyle is perhaps best remembered today for his eponymous law, which he formulated via experiments with his air pump, a centrepiece of early Society meetings. Not only did it help him to determine the relationship between pressure and volume, it also facilitated his work on food preservation. Believing the corruption of food to be the result of exposure to air, Boyle set up a series of experiments in which various foodstuffs were preserved in a vacuum. The results suggested that food could stay fresh for many months by this method: a piece of roasted rabbit, for example, was ‘two months and some few days after taken out without appearing to be corrupted, or sensibly alter’d in Colour, Tast, or Smell’.

First page of Boyle’s New experiments about the preservation of bodies in vacuo Boyliano (1674)

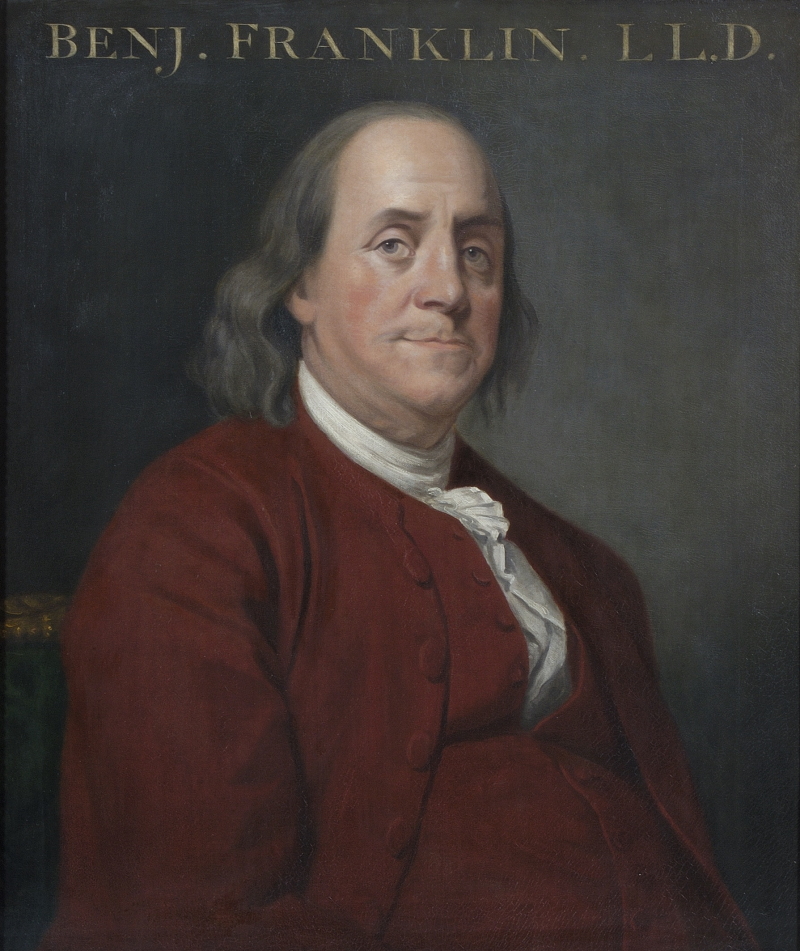

From one of the Society’s Founding Fellows, to one of America’s Founding Fathers, Benjamin Franklin FRS (1706-1790):

Franklin by Joseph Wright (1756-1793): RS.9270

Franklin by Joseph Wright (1756-1793): RS.9270

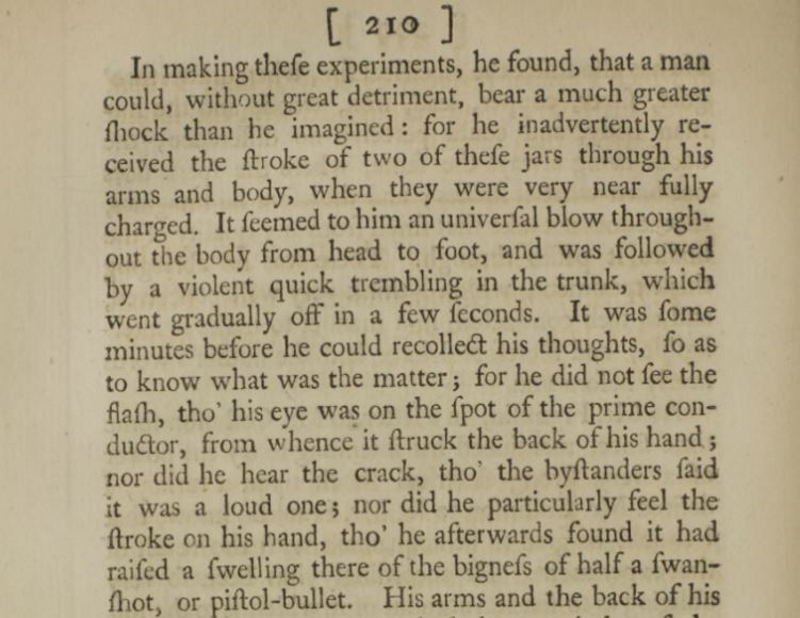

Like Boyle and his air pump, Franklin also has a particular object closely associated with his scientific legacy: the kite, which he famously used to demonstrate the electrical nature of lightning. However, there is an earlier food-related experiment that, one could argue, helped him prepare. Franklin is said to have been a bit of a foodie, and a big fan of turkey. For some reason he believed that a turkey killed with electricity would be tastier than one dispatched by more conventional means. His experiment, therefore, set out to prepare a turkey dinner with static electricity collected in Leyden jars. As described in this paper, he missed his mark on one occasion, absorbing the electric shock intended for his meal himself:

From ‘An account of Mr. Benjamin Franklin’s treatise, lately published, intituled, Experiments and observations on electricity, made at Philadelphia in America’, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1751)

From ‘An account of Mr. Benjamin Franklin’s treatise, lately published, intituled, Experiments and observations on electricity, made at Philadelphia in America’, in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society (1751)

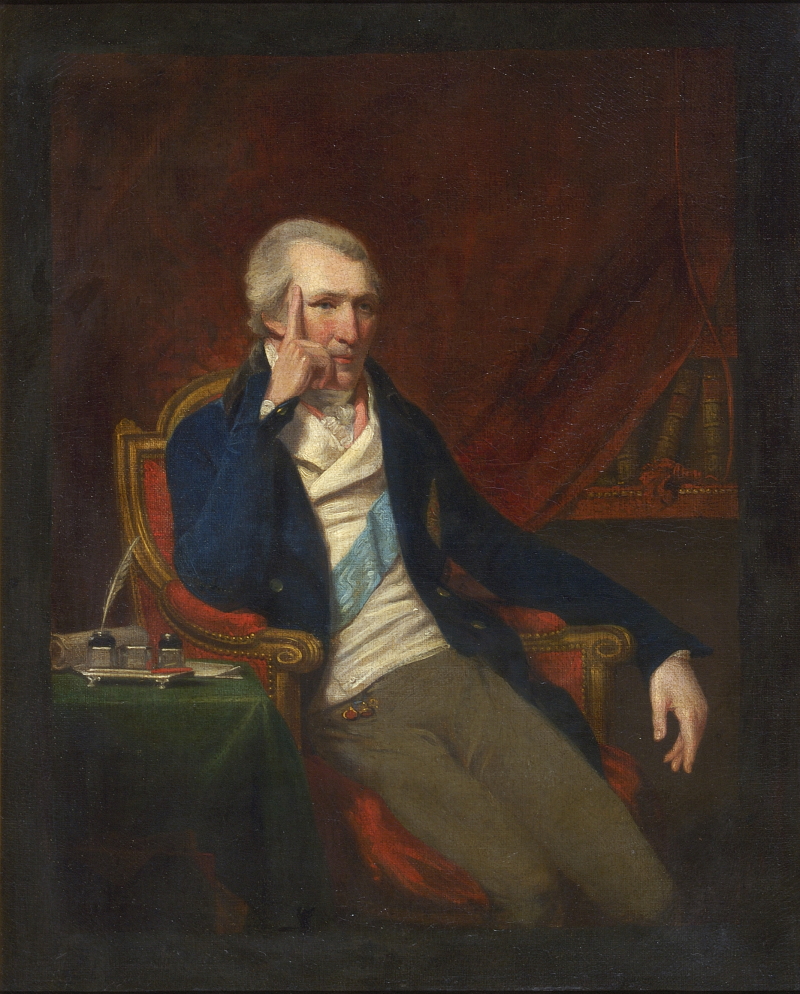

Franklin and our next Fellow may not much appreciate being mentioned in such proximity, given that they lined up on opposing sides in the American Revolutionary War. But one cannot write about food without mentioning Sir Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford FRS (1753-1814). I’ve always thought he looks a little bored in our likeness of him; however, he is impassioned in his writing on food: ‘As providing subsistence is, and ever must be, an object of the first concern in all countries, any discovery or improvement by which the procuring of good and wholesome food can be facilitated, must contribute very powerfully to increase the comforts, and promote the happiness of society’.

Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, by John Raphael Smith (1752-1812): RS.9257

Benjamin Thompson, Count Rumford, by John Raphael Smith (1752-1812): RS.9257

To this end, Thompson invented many useful domestic cookery appliances and made great progress in the roasting of meat, where his aim was to avoid having the skin ‘scorched and dried’ but the flesh uncooked within. One encounter with a shoulder of mutton was something of an accident but is often credited as the first example of slow cooking in the West. He tried to cook the shoulder in a machine he'd invented to dry potatoes with hot air, giving up after three hours, feeling ‘rather out of humour at my ill success’. However, the mutton remained in the apparatus until the next morning when Thompson returned to find it perfectly cooked.

Though a bit of a jump forward, I’ll finish with Elsie Widdowson FRS (1906-2000) and Robert McCance FRS (1898-1993):

Widdowson and McCance by Margo Bulman (1913-2003): RS.13615 and RS.13614

Widdowson and McCance by Margo Bulman (1913-2003): RS.13615 and RS.13614

As discussed in a previous blogpost, McCance and Widdowson are best known for their work on British nutritional tables and wartime food rations. However, they also shared an interest in ‘food art’. Our collection of Widdowson papers features a box of her notes on representations of food in oil paintings of the fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. She was interested in what they could tell us about which foods were bought, sold, cooked and eaten in past centuries. She appears to have written papers and given talks on the subject, though she did open these by making clear this research was not a ‘serious exposition on art’, but a happy by-product of time spent exploring galleries when abroad for scientific conferences.

Still Life with Golden Goblet by Pieter de Ring, and Still Life with Artichoke, Fruit in Kraak Porcelain Ware, a Salt Cellar/Pepper Castor by Osias Beert, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Still Life with Golden Goblet by Pieter de Ring, and Still Life with Artichoke, Fruit in Kraak Porcelain Ware, a Salt Cellar/Pepper Castor by Osias Beert, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

Similarly, McCance discussed what we could learn about food from another art form – nursery rhymes. He considered, among other things, the fact that Little Tommy Tucker (who sang for his supper) was rewarded with white bread, an indication of the high regard it was held in at the time, for the simple reason that white flour baked a larger, softer loaf or cake, than wholemeal flour.

From looking at art through food, to food through art, our painted and sculpted portraits have, quite pleasingly, taken us full circle. Though there is much, much more food-related material to explore within our collections, surely for now, it’s time for a snack…